The Science of Seed Starting

For success with seeds, it helps to understand a few key factors

Seeds are little miracles that transform the world. In the wild, these tiny amalgamations of DNA can be stored away for years, waiting for the right conditions to turn a barren desert, a fallow forest floor, or a trampled prairie into an oasis of bloom. In our gardens, starting seeds is one of the easiest ways to make more plants. Volunteer seedlings can be blessings, appearing year after year to fill holes in the landscape, or they can be curses, in the form of weeds that seem to spawn out of nowhere. I teach students with little to no background in growing plants, and it is always inspiring to witness their wonder when they see the first little leaves emerge from seeds they have planted. In that rich moment, they have become gardeners. What do seeds require to germinate? Here’s what you need to know.

What seeds need: The big three

Seeds need an environmental trinity to be able to germinate: the right temperature, abundant moisture, and adequate oxygen. If there is an absence of any of the three, you will not see emergence. Let’s look at each factor in more detail.

1. The temperature must be right

Seeds, like Goldilocks, want their environment to be just right when they germinate—not too cold or too hot. At the extremes, germination may take weeks or months. But if temperatures are in the optimal range, seedlings will be up in a few days.

We see this in the garden when winter-annual weed seeds begin to germinate in late summer or fall after the temperature drops. Seeds have had access to moisture during the summer, but here they are popping up at the first signs of cooler weather. I have also seen the effect of temperature on germination in spring, when gardeners complain about warm-season crops like peppers taking forever to germinate. Usually they are placed on chilly windowsills and don’t emerge for a few weeks.

Trays of seeds that need warmer temperatures can be put on a seedling heat mat or on top of a refrigerator, freezer, or water heater. Just be sure that once leaves emerge you get them into the right light conditions as quickly as possible. If you are trying to keep seeds cool, try placing cardboard over them and moistening the soil underneath them once a day.

2. Water gets things going

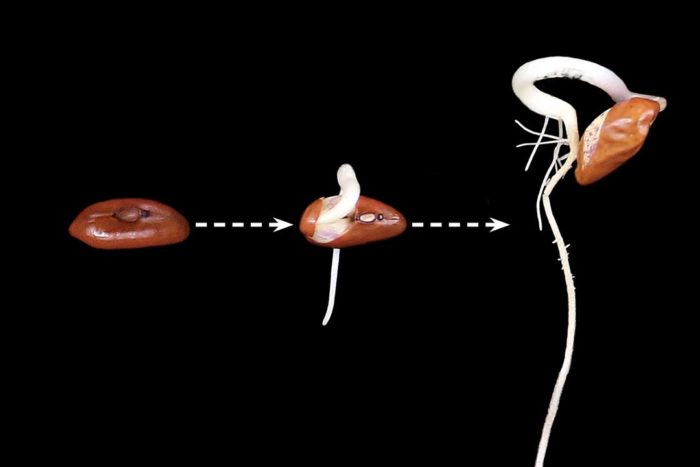

Germination is a bit like starting a car. Think of temperature as the key that controls whether germination starts or not, and water as the fuel that really gets things going. Once water is imbibed by the seed, many metabolic processes prime the seed for the emergence of root and shoot.

Seeds must have close contact with the growing medium to make sure that they can get enough water to germinate. Some species, such as basil (Ocimum basilicum), even produce a mucilage that plumps up around the seed to help ensure that it is surrounded by the wet stuff.

A common issue with seeds germinating is that they do not get enough water. There are multiple approaches to make sure seeds stay wet. Seeds by themselves can be placed in damp paper towels in baggies before sowing into a tray. If the seeds are large enough, they can be soaked overnight in a saucer. Seeds sown directly in trays can be covered with moist newspapers or put into a mist chamber to keep the surface of the planting medium moist. If seeds are planted outside, morning and evening irrigation is usually enough to keep them hydrated. If the weather is extremely dry, you can plant seeds in a slight trench made with a hoe to catch water (photo) or cover the seeds with cardboard and moisten underneath once a day.

3. Oxygen is the often forgotten element

Seeds use oxygen too! This may surprise some people, since the focus on gases with plants is usually on the carbon dioxide plants use to make sweet sugars. Just as you need plenty of oxygen when you exercise, a seed must take in oxygen to break down its stored food supply during germination. If seeds are planted too deep, if they sit in too much water, or if a thick crust forms on the soil, they may be starved of oxygen. Avoid creating these conditions when sowing.

Troubleshooting: What if my seeds don’t germinate?

If a viable seed is exposed to the appropriate temperature, moisture, and oxygen levels and nothing happens, a condition called dormancy may be to blame.

Dormancy makes sense from a plant’s perspective. Interacting with their environment over time, many wild plants developed mechanisms to prevent germination until conditions were favorable for seedling survival. Some vegetables and flowering annuals grown by humans over the millennia have had seed dormancy bred out of them, but many species still show these basal traits.

Three common dormancy scenarios (and how to overcome them)

1. Water can’t penetrate the seed coat

Some seeds have a very thick seed coat that may also contain water-repellent molecules. A thick coat makes sense for seeds that must endure freezing and scorching weather, traveling through animals’ digestive systems, or being trampled by herds. Under conditions like these, natural selection would have favored seeds with a robust physical barrier over thinner-walled counterparts.

To encourage germination, you can scarify (damage) the water-resistant seed coat. Use fingernail clippers, a file, or sandpaper to remove the seed coat until you see the underlying flesh. Some horticulturists soak the seeds in hot water (140°F) or acid, but these techniques require more safety precautions.

Seeds with thick coats

|

|

|

|

- Eastern bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana, Zones 3–9)

- Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioica, Zones 3–8)

- Texas bluebonnet (Lupinus texensis, Zones 3–8)

- False indigo (Baptisia australis, Zones 3–9)

- Goat’s rue (Tephrosia virginiana, Zones 3–9)

2. Hormones are preventing germination

Many temperate perennial and woody species that shed seed late in the season have evolved a hormonal strategy to prevent seeds from germinating before winter. The two main hormones involved work against each other: abscisic acid induces dormancy, and gibberellin releases it.

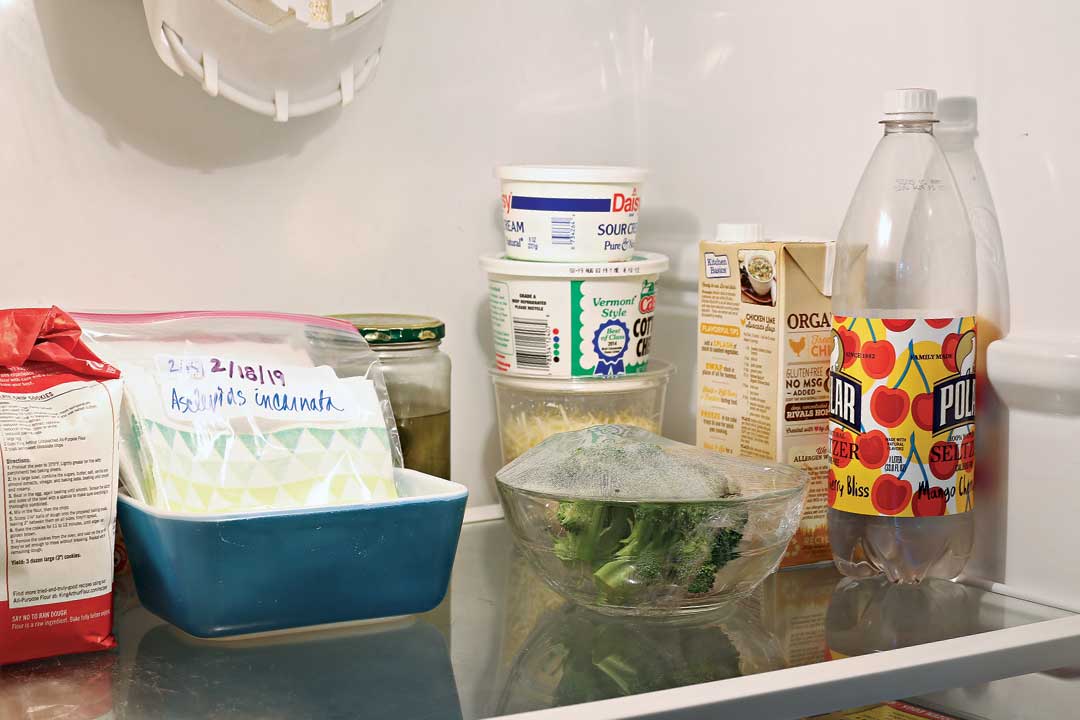

For these seeds, a cold, moist treatment called stratification can shift the hormones from inducing dormancy to promoting germination. The name comes from horticulturists who stacked seeds outside in layers during the winter to expose them to dormancy-breaking weather conditions. The hormonal shift that occurs during stratification is like an alarm clock, letting seeds know it is time to wake up. If stratification does not occur, the seeds will snooze until they get their cold-and-moist beauty rest. An easy way to stratify seeds is to place them in a damp paper towel or soilless substrate, seal them in a labeled plastic bag, and place the bag in the refrigerator for one to three months. In some cases you may need to alternate warm and cold stratification to allow the embryos (baby plants) to fully develop.

Seeds that need cold and moisture to germinate

|

|

|

|

- Red buckeye (Aesculus pavia, Zones 4–8)

- Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa, Zones 3–9)

- Pawpaw (Asimina triloba, Zones 5–9)

- Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana, Zones 4–9)

- New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis, Zones 5–9)

3. The seeds have no access to light

It makes sense that some seeds would need light to germinate. Because a plant cannot move once it sprouts, waiting until there is ample light is a good adaptation to have. We observe this requirement in many species that grow on the forest floor or in swamps where water is usually abundant; thus, it is believed that light would be a better trigger for when to germinate. (Interestingly, spider lily [Hymenocallis occidentalis, Zones 5–8] actually has a green seed coat that must photosynthesize for germination!) When planting light-sensitive seeds, sprinkle them on top of the growing substrate, lightly press them into it, and then place them under lights or outside to germinate. Because they are on the surface, take extra care to ensure that they stay moist.

Seeds that need light to germinate

|

|

|

|

- Lettuce (Lactuca sativa, annual)

- Oakleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia, Zones 5–9)

- Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis, Zones 3–9)

- Foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis, Zones 3–8)

Jared Barnes, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of horticulture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in