How and When to Water Your Garden

Learn some tips and tricks to give your plants the proper amount of moisture

Watering a vegetable garden can be as easy as watching the rain, or as ridiculous as feeding plant limbs intravenously. I don’t know anyone who takes the hospital bed approach to plant nourishment. I do know people who let the heavens do the heavy labor when it comes to irrigation. They run for the hose only after the rain has turned irregular.

Somewhere in between is the ground that will give your plants the right amount of water to flourish. Really, without being in your garden, no one can tell you how much water this will turn out to be. Each garden has its own idiosyncrasies that must be observed.

Learn more: Build a rain garden to catch water runoff

8 Watering Tips

1. Get to know your soil. Dig into your garden and find out whether you have clay or sandy soil. It makes a big difference in your drainage.

Clay-laden soil presents special watering challenges. Clay has an electrical charge that draws water, pulling it away from plant roots. In dense clay, little room exists for passages that permit the exchange of essential gases with the air above ground. Clay also drains slowly.

Water flows more easily through sandy soil. But if it’s too sandy, water may leach out too quickly and take dissolved nutrients with it. Both clay and sandy soils can be turned into a preferred loam by mixing in organic material, such as compost.

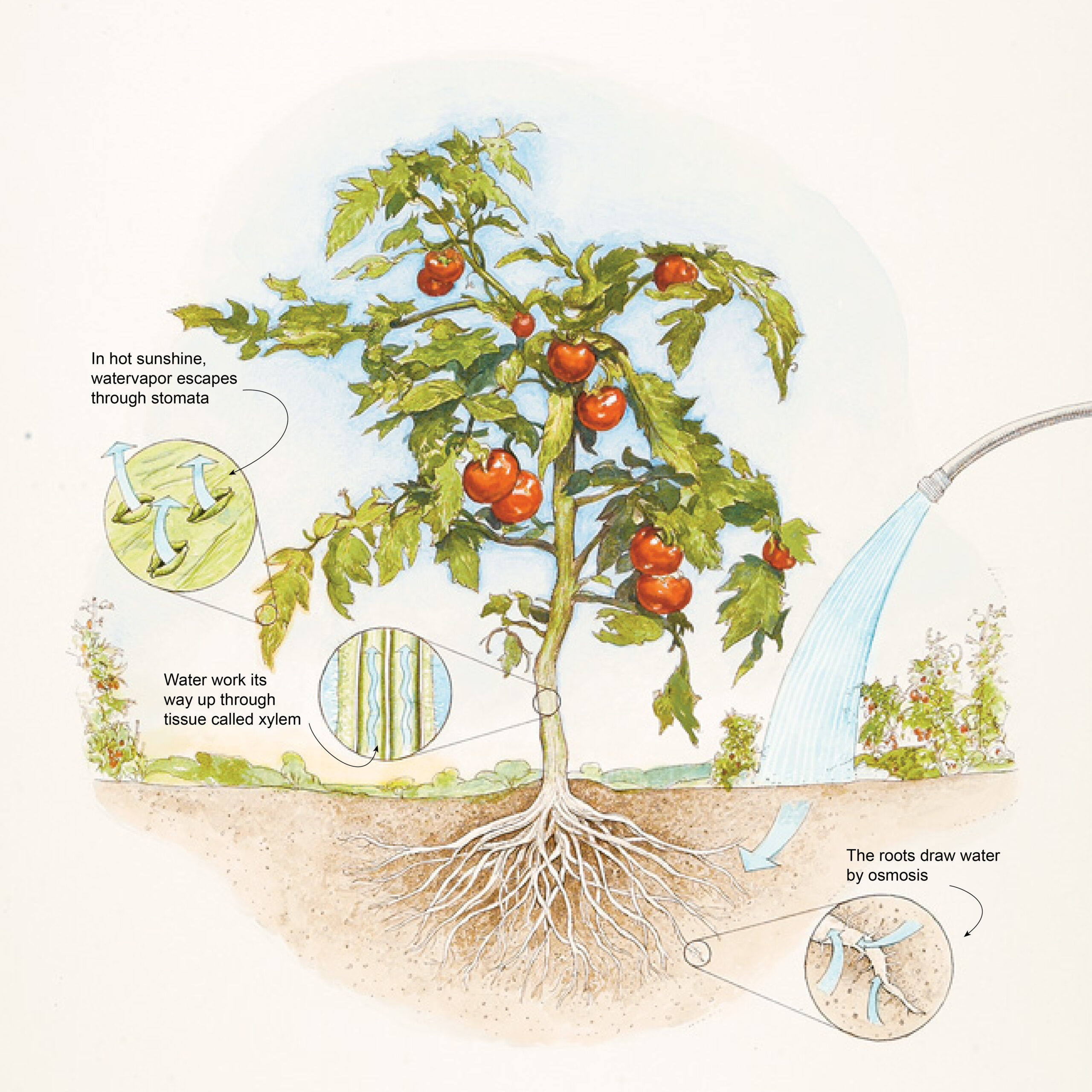

What happens when you water your plants

Speaking of watering, it’s worth noting why you should go to the trouble. One reason vegetable plants need water is that they absorb nutrients in dissolved form. And water moving into leaves plays an important role in photosynthesis. Along the way, plants employ a marvelous method of water intake and distribution. Here’s how it works: The roots draw in water by osmosis, that is, if pressure inside the root cells drops below the pressure outside, water moves in to equalize it. The nutrients move in, too. When the water storage structures get too full, they expel water. But the nutrients stay. Then a kind of botanical bucket brigade driven by the leaves takes over, drawing water through plant stems. Heat from the sun vaporizes water in the leaves, which generates pressure that forces water out through tiny pores called stomata. This helps cool the plant. When the leaves recognize the loss of pressure, they again start pulling in water from the stems so long as it’s available. As water moves in, cells surrounding the stomata expand, pressing open the stomata. This allows entry of the carbon dioxide critical to photosynthesis. The idea in watering is to keep this system operating smoothly. |

You can check how fast your soil absorbs water using any type of cylinder, such as a coffee can with the top and bottom removed. Push one end into the soil a few inches. Fill the can with water and let it drain completely. Fill it again, and then see how long it takes for the water level to drop 1 in. If it takes more than four hours, you’ve probably got a drainage problem that could harm plant roots. Raised beds may be the solution if that site is your only option for a garden.

When I lived in southwest Florida I had the opposite problem. Our garden soil was dredge spoil, essentially sand. Water drained faster than you could say alligator. It took the addition of several 50-lb. bags of compost to the little garden strip to slow it down.

2. Keep water percolating in the zone. The root network is the critical area of watering. And the depth varies among plants. In general, we’re talking about the first 6 in. to 8 in. of soil. Keeping that section moist should prevent plants from being parched by thirst or stressed from binge drinking. With a good garden soil, you should be able to squeeze a little dirt into a clump that will break up easily if you gently bounce it in your palm.

3. Water before you mulch. Mulch helps conserve water in your soil by shielding the ground from the hot rays that burn off moisture. But it’s a good idea to soak the soil before you lay on that first layer of mulch. Just as the mulch hinders evaporation, it also slows penetration of moisture to the roots. It’s more efficient to get the water down first, then mulch. It also may initially save your plants from waiting for water to percolate through the mulch when they are accustomed to getting it right away. The mulch, of course, also will suppress those thirsty weeds trying to elbow their way to the fountain.

4. Read the leaves. Don’t let leaves fool you. If they’re drooping in the hot, midday sun, you need not necessarily be alarmed. The plants may just be protecting themselves by exposing less surface to the sun and conserving water, unable to pump enough to offset the loss through the leaves.

If the same plants are drooping in the morning or at night, then you can rev up the water wagon. But don’t cause a flood. Saturated soil drives out the air roots need, and plants will drown. And there’s no reason to water the leaves. That can encourage a variety of fungi that develop in moist conditions, causing mildew and blight.

5. Get a bigger bang per bucket. Consider the life cycle of the plants in your garden when you water. For example, recent transplants need frequent, light watering to accommodate their shallow, young roots and ease the shock of being pulled from their six-packs. Steady watering also is critical at the time of flowering and fruit formation. For some crops, like tomatoes, yields may improve but some flavor may be lost with too much watering as fruit ripens. And with carrots and cabbages, for example, watering should be reduced as the crop reaches maturity to keep the vegetables from splitting.

Once plants are established, more harm than good is done by giving them a daily sprinkling. If only the soil surface gets wet, roots will look up, not down, for their drinks. Deep, less frequent watering works better.

6. Grow thirsty plants together. If you have the space in your garden, you can save yourself some trouble by grouping plants according to their water needs. For example, you wouldn’t want to plant your herbs next to your lettuce, even though they often wind up together in the salad bowl. Generally, herbs thrive in drier areas, while lettuces like it lush. If the lettuce gets the water it needs, the herbs are likely to be lush, too, but tasteless. If you water to suit the herbs, chances are the lettuce will turn out bitter. By grouping the plants according to their water needs, you won’t waste water where it isn’t needed.

7. Choose your time wisely. Early morning, late afternoon, and evening are usually best for watering because the cooler temperatures mean less water will evaporate. Limiting your watering to these times is a particularly good idea if you use overhead sprinklers. Under bright sunshine, water droplets intensify the rays and can singe the leaves. It’s also safer not to water at night, as the leaves will remain wet, which may encourage disease. In arid places, however, some people decide to risk night watering to give the water longer to soak into the soil and cut evaporation from the sun.

8. Know when to say when. According to a common rule of green thumb, a garden needs about 1 in. of water per week. Divining how much the garden is actually getting can be a little tricky. You can estimate by using a rain gauge to track precipitation. The gauge should be near the garden but where water splashing off pavement or overhangs won’t affect the reading.

When it comes to your own watering, the amount can be checked with a flow meter attached to the garden spigot. About 60 gallons will provide about 1 in. of water over 100 sq. ft. In especially dry climates, or if you’re using raised beds, more water may be needed.

There are myriad methods to deliver the water. Some gardens are small enough to water by hand. The large size of others or a lack of time may require more elaborate arrangements, including sprinklers, soaker hoses, or drip irrigation systems. You have to balance your commitment with the needs of the plants and the results you expect.

Predicting the weather

Predicting the weather is like writing—anybody can do it, but not everybody gets paid for it. Before the ascent of farmer-forecaster Willard Scott, gardeners looked to nature for weather signals. Many still do, and sometimes they are as right as TV meteorologists.

Sunny days to come:

• Heavy dew on the evening grass

• Swallows soaring high

• Beetles and bats flying in the evening

No need to water:

• Spiders reinforcing their webs

• Trees turning up their leaves

• Clover contracting its leaves

In the end, though, the verse by Reginald Arkell may sum it all up:

A gardener’s life

Is full of sweets and sours.

He gets the sunshine

When he needs the showers.

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #9 (June 1997).

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in