How to Water Your Garden Sustainably

These tools help you put water only where you and your plants want it

While I consider the swish of an overhead sprinkler the signature sound of summer, I’ve come to realize that literally every drop of water counts, so I try to use it with care. And for the needs of a garden bed, an overhead sprinkler is just not the ideal way to go. That’s not to say it doesn’t work. It’s fine for a lawn, where broad areas share an almost identical thirst. The trouble starts with mixed plantings, where varied water needs can’t be met by a “one size fits all” approach. And that’s what overhead sprinklers provide: equal-opportunity irrigation that delivers as much water to parched plants as to sidewalks, pathways, and plants that aren’t even slightly thirsty. Worse, artificial rain soaks the foliage of every plant it touches. Some of that water is rapidly lost to evaporation, but the rest might act like mini magnifying glasses, focusing the sun’s rays enough to burn spots in the leaves. Worse yet, damp foliage creates the perfect environment for fungal diseases such as mildew and rust. Learn more: Getting Control of Insects, Weeds, and Diseases Free Webinar (Recording).

The trouble starts with mixed plantings, where varied water needs can’t be met by a “one size fits all” approach. And that’s what overhead sprinklers provide: equal-opportunity irrigation that delivers as much water to parched plants as to sidewalks, pathways, and plants that aren’t even slightly thirsty.

One of my main gardening aims is to welcome Darwinism into my garden, letting natural selection play a role in its design. I don’t coddle plants and prefer those that thrive with no more water than nature provides. So I limit watering to new plantings while they are getting established, to plants in containers, and to small populations of especially thirsty plants, such as hydrangeas.

I’ve experimented with different watering gizmos, studied how plants use water, and adapted the best practices to my landscape. I’ve found three commonly available accessories that deliver water efficiently without a lot of time and effort: the Noodlehead sprinkler, a watering wand, and a soaker-hose ring.

Pinpoint water delivery with a Noodlehead

The aptly named Noodlehead sprinkler looks like an overturned, 12-legged bug. Each of the sprinkler’s 12 “legs” is actually a tiny, flexible, nozzle-tipped hose that can be positioned to direct a tiny stream of water wherever you want it to go. This is an overhead sprinkler that allows you to customize the area it covers. Although it shares many of the drawbacks of conventional overhead sprinklers, it doesn’t waste nearly as much water. Since it can create almost any pattern you want, it’s perfect for targeting a few select plantings within an area. I just set the Noodlehead into place, turn on the water, and adjust its fright wig of tiny hoses until the water is going exactly where I want it.

Areas just a few feet in diameter can be easily covered by partially turning on the hose so there’s a limited flow. By turning on the water full force, the Noodlehead can cover an area up to 20 feet in diameter. I can further modify its field of coverage by putting the little gizmo on a bench or tabletop to help the water vault over any large foliage that might be in the way.

Noodleheads come with a small stake that can be used to affix the sprinkler to the ground, which is handy since a twisted hose can easily exert enough torque to topple a Noodlehead. An optional, taller stake is available for use with the Noodlehead; it’s useful if there are no other table- or chair-top perches available. These sprinklers cost less than $20. If you can’t find one locally, try the company’s Web site (noodleheadsprinkler.com).

Watering wands are best for containers and hanging plants

For plants in pots, and especially those in hanging baskets, a watering wand is the ultimate device for anyone who hasn’t rigged up a drip-irrigation system. The wand gives me a few extra feet of reach, so it’s great for targeting plants in hanging baskets, pots on the ground, or container plantings positioned behind other containers or set into a border. Wands are also good at getting to plants in the ground that are a little hard to reach.

The watering wand—basically a watering rose on the end of a stick—allows you to poke its nose under a plant’s foliage and direct a spray of water right at the root zone, exactly where the plant needs it. A few seconds is enough to saturate the soil in most pots, and even the largest pots don’t need more than a minute or so. I like wands with an adjustable rose so I can dial up anything from a fine spray to a coarse stream. I find the coarse stream too forceful for anything but filling a watering can, but the fine spray is perfect for watering large seedlings gently enough to prevent accidentally dislodging or flattening them.

In a pinch, a watering wand can also serve as a soaker hose. I just turn down the water so it’s barely flowing, then place the wand just inside the drip zone of whatever plant needs a drink. Watering wands are widely available but can be expensive, sometimes costing in the range of $20 to $30.

A cheap and easy way to water a new tree or shrub

Soaker-hose rings are ideal for establishing trees or shrubs

Soaker hoses slowly emit droplets of water along their length. They are ideal for delivering the long, slow soaking that some plants thrive on. They’re a staple for many gardeners, but I’ve seen very, very few soaker-hose rings at work, even though they are perfect for getting a new tree or shrub through its first season in the garden. A soaker-hose ring is a small donut of soaker hose, approximately 18 inches in diameter, attached to a Y-shaped connector that in turn connects to a traditional hose. Simply unscrew one end of the ring, arrange it around a small tree or shrub, then reconnect it and turn on the water. It’s a great solution for delivering a good, deep drenching right to the root zone of the targeted plant.

I use quick-connect hose accessories that allow me to simply click the soaker hose on and off a normal hose, as if I’m using Tinkertoys. I can set up a soaker-hose ring to a new plant in just a few seconds and let it run without worrying about wasting water. I need to let the hose trickle for a few hours to provide a really good drink, but other than turning the water on and off, a mini soaker-hose setup doesn’t need tending. I simply set it up, turn it on, and busy myself elsewhere in the garden, returning only when it’s time to get the soaker around a new plant. Soaker-hose rings generally cost under $15 at your local garden center.

These crystals let you water less

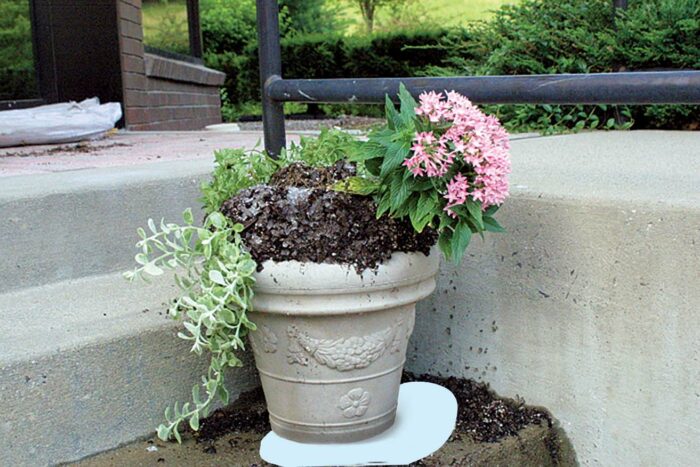

I sometimes use water-absorbing crystals in my container plantings. They can make the difference between watering daily and watering weekly, though I’d never trust them to keep the thirstiest of plants happy for much more than an extra day or two without a real drenching. I do have a few containers placed outside the range of easy hose coverage, and I don’t get to them quite as regularly as I should. For them, the crystals make all the difference between a radiant display and what I might charitably call a dried arrangement.

Water-retaining crystals can also be added to an in-ground planting and are reputed to retain their water-holding capability for five or more years, so they’re well suited for helping a moisture-loving plant settle into a new home. My own choice is not to use them in the soil, in keeping with my primarily organic approach to gardening. A pound of the crystals costs between $10 and $15.

Too much is a bad thing

Wet the crystals before you mix them into the soil. Once wet, the crystals expand to many times their original size thanks to all the water they’ve absorbed. The first time I used water-retaining crystals, I mixed them dry with soil, planted up a pot, and then added water. The crystals expanded so much that there was nowhere for them to go but out of the pot in great oozings of gelatin-like slime. Used properly and with restraint, prewetted water-retaining crystals can help create a far prettier garden picture.

Comments

The research of Linda Chalker-Scott has demonstrated that those water-absorbing crystals are not effective. Potting soil is a careful balance of soil and water; if there is too much water in the soil, roots will not receive the air they also need.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in