The Art of Watering the Garden

Quench your plants’ thirst with less waste

Have you ever noticed how vibrant your garden looks after a steady, soaking rain? Natural rainfall infiltrates soil in a way that is hard to match with artificial watering. We know that swinging a hose around in the garden for 20 minutes isn’t going to do the job, but what will? Good observation skills, knowledge of your plants’ water needs, and a bit of creativity will help you keep your plants properly watered.

What happens when you add water to soil?

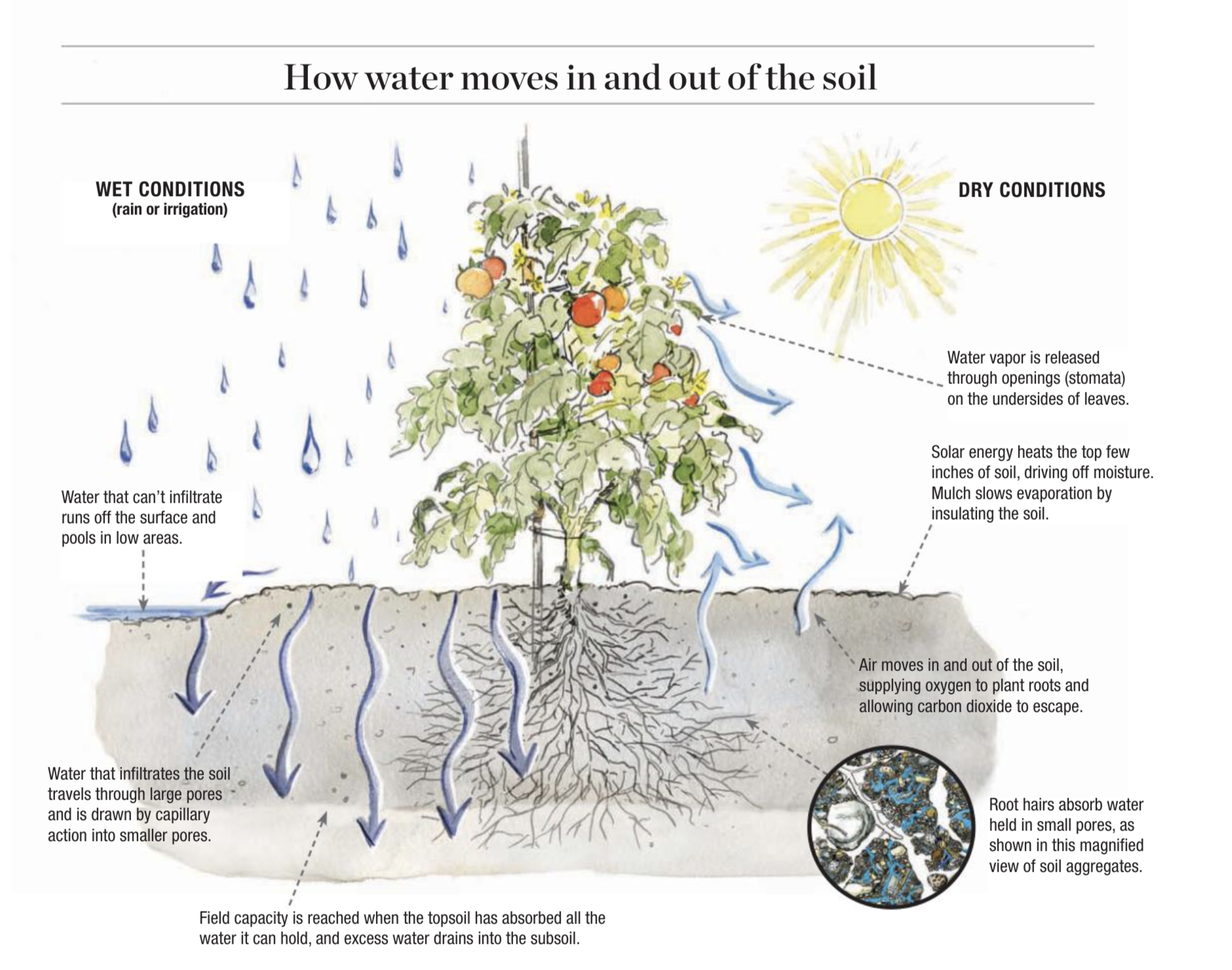

One of the most important characteristics of healthy soil is pore diversity. Pores are the spaces between soil particles that can be occupied by either water or air. Large pores allow water to drain freely through the soil, release carbon dioxide, and supply plant roots and microbes with oxygen.

Between the larger pores, tiny soil particles are held together in crumbs, or aggregates, by fungal hyphae, root hairs, and the sticky residues left behind by living things. Within the aggregates, medium and small pores absorb water by capillary action as it drains down thorough the larger pores. The smallest pores remain consistently moist, making them the perfect habitat for bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, which digest organic materials and release nutrients to root hairs.

When it rains, or when we irrigate, water seeps down through large pores and wicks up into the aggregates. When this wetting front advances through and beyond the root zone by the force of gravity, the soil is said to be at field capacity. When we water, this should be our goal. Failure to apply enough water to reach field capacity deprives roots of the nutrients found in deeper soil.

Plants have different water requirements, and an observant gardener quickly learns which plants are the thirstiest. Annuals, including vegetables, have only a fraction of the year to develop roots, and most will require regular watering to thrive. Perennial roots, which have more time to develop, can find water deeper in the soil and farther from the crown. As a general rule, perennials will require less frequent watering, except during the establishment year. A plant’s water use will also vary over the course of the year. When you notice vigorous vegetative growth or ripening fruit, expect an increase in water demand.

Soil texture plays a major role in the frequency and depth of watering needed. In a light-textured sandy soil, water washes quickly through large pores, leaching soluble nutrients away from the root zone. Moisture moves more slowly through heavy, fine soils, where too much water, added too quickly, floods soil pores and runs off the surface, carrying small particles with it.

Evapotranspiration is another variable affecting water demand. This is the combined effect of water evaporating from the soil surface and being taken up by plant roots and released as vapor through leaf stomata. Water loss will be most pronounced in unshaded areas and in dry, windy conditions.

Mulching the soil surface will dramatically reduce evaporative water loss and, unless you live in a rain forest, should be considered mandatory. Organic mulches like straw, bark, or wood chips are best. Unlike black plastic, an organic mulch will slow soil warming, and by allowing water to naturally infiltrate, a top dressing of organic matter will improve soil structure and encourage microbial activity.

Slow, gentle irrigation is best

Regardless of soil texture, the best irrigation methods deliver water slowly and gently. A strong stream aimed straight at the soil will expose feeder roots and destroy surface aggregates. When surface aggregates are broken up and displaced, soil pores can become blocked, making it more difficult for plant roots to get the oxygen and water they need.

To decide if you need to water, try checking the moisture status of your soil with this simple squeeze test: Take a palm full of soil from about 6 inches down and try to form a ball in your hands. If you have a fine- to medium-textured soil and it won’t hold together, you probably need to water. In coarser, sandier soil, where it’s hard to get a ball to stick together at all, you’ll need to water frequently unless you grow drought-tolerant species. Watch your plants for signs of drought stress, but remember that wilt does not always signal water need. Root disease, stem borers, or extreme midday heat can also cause wilt.

For lovers of technology, there are devices that sense soil moisture. Sensors are installed at 6- and 12-inch depths for the season. There are two types of sensors: One gives an electronic reading, and the other uses a vacuum gauge. These readings aren’t exact, but they will give you a relative sense of how water levels fluctuate in the soil. Unfortunately, sensors aren’t cheap, and you’ll need two units per location.

Every watering should be deep

Rules of thumb—for example, “Apply 1 inch per week”—only work for crops growing in uniform conditions. Instead, make it your goal to water only as needed and, when you do water, to wet the soil around plant roots to field capacity. Let the soil dry out between waterings, but not to the point of stressing the plants.

If you use sprinklers, prevent waste by knowing how much water they apply in a given amount of time. Place several cans at various distances from a sprinkler, run it for a half-hour, and calculate the average water depth in the cans. Check drip systems by placing cans under emitters. Keeping records can help you fine-tune your watering schedule.

Water is the lifeblood of your garden. There are many inexpensive and effective products that can help you to deliver just the right amount, but they work only if you remain attuned to the needs of your plants. Excessive automation removes you from this satisfying and intuitive experience. So get your hands dirty, see what it really feels like 6 inches under, keep good records, and consider all

the factors week to week. Your thirsty plants will thank you for it.

Basics

A Palette of Watering Options

When choosing a delivery method, the variables to consider are efficiency, expense, convenience, flexibility, and effectiveness.

Sprinkler options

For ground covers or lawns, sprinklers are an obvious choice. Options range from simple hose attachments to permanently installed, computer-controlled systems.

|

Pros • Sprinkling can quickly relieve heat stress. • Watering all soil, not just root zones, supports the underground ecosystem that keeps your plants healthy. • Sprinklers wash dirt from leaves in dry weather, increasing photosynthesis. |

Cons • Wind will cause drift and evaporation before moisture hits the ground. • Excessive leaf wetting can promote foliar disease. If you don’t mulch, you will be watering the weeds. |

Oscillating sprinkler

The classic oscillating lawn sprinkler is easy to set up, portable, and cheap, but it deposits water unevenly. It can be adjusted to sweep from one side to the other, either partially or fully. The more water pressure from your spigot, the farther the reach. Use these if you must, but you can do better.

Impact sprinkler

An impact sprinkler can be set to rotate through a full or partial circle. You can adjust the spray distance (20 to 40 feet) and droplet size. Better units provide more even distribution. Your water pressure must be at least 15 to 20 psi to run these, but you’ll be able to run only two at a time to get significant coverage. Heads can be mounted on spikes and left in place in key locations. Impact sprinklers can be fed by movable garden hoses or by polyethylene tubing that is left in place.

Microsprinkler

A microsprinkler covers a relatively small 5-foot radius in 90-, 180-, or 360-degree patterns. These units are surprisingly affordable and operate on little pressure. They may be fed in series from an inexpensive polyethylene supply line. In-line shutoffs can be installed for zone control. Many small heads deliver more consistent water to complex terrain than a few larger units. Consider the effects of wind when placing the heads, since these tend to put out a finer mist than larger sprinklers.

Drip-and-trickle system options

These systems deliver water slowly, letting it seep into the root zone where it can be absorbed by soil aggregates.

|

Pros • This is the most efficient watering method. • Installation is straightforward and may be customized to suit any garden. |

Cons • Water pressure must be regulated to keep it between 8 and 15 psi. • Separate zones may be required for diverse plantings. |

Drip tape is flat hose made of flexible multilayered polyethylene. It delivers water evenly along its length unlike soaker hoses, which tend to deliver more water at the end closest to the source. Drip tape is best for gardens with straight rows. It can be placed on the soil surface, and may be covered with plastic mulch. But don’t cover it with organic mulch, since voles can learn to bite through tapes for a watery treat.

Emitters, like microsprinklers, can be connected to a poly hose that runs through garden beds. Emitters and drip tape are available with different flow rates; stick with low-flow emitters, and you’ll be fine. These deliver ½ gallon per hour, and you can run many at once. Inspect your emitters periodically for leaks, clogs, and separated fittings.

—Andy Radin is a research associate and agricultural extension agent at the University of Rhode Island Department of Plant Sciences and Entomology.

Comments

This is the best idea!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in