Winter Squash for Tight Quarters

Compact varieties save space without sacrificing flavor

If you have ten acres of garden, you won’t mind if winter squash vines sprawl 8 ft. in every direction. But if you have a small backyard garden, you can’t afford to be so generous. I’m often asked if the space winter squash takes up is worth the sacrifice. My answer is, yes, especially if you grow bush or semi-bush varieties. I include a handful of delicious ones among the hundreds of squash I grow for seed saving. With these compact plants, the return from even a small patch is high in both quantity and quality.

In addition to being both delicious and prolific, bush squash are also quick to mature—75 to 85 days for most varieties, compared to more than 100 days for many vining squash. In areas with a short growing season, bush varieties make a winter squash crop possible. In areas with a longer growing season, they’re an ideal second crop. Late plantings have the additional bonus of avoiding some insect pests.

In a 4-ft. by 8-ft. bed, you can plant three hills of bush squash with two or three plants per hill. A planting this size might yield several dozen squash. Not bad from a plot the size of a sheet of plywood.

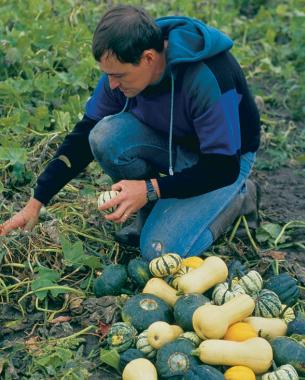

Bush Squash Are Short on Leaves but Not on Fruit

Photo/Illustration: Mark Vassalo

A bush squash is one that never produces small side vines. The plants typically take up an area no bigger than 3 ft. by 3 ft. There are also semi-bush squash, which have dense vines that begin to sprawl but never get very far from the center plant. Semi-bush plants ultimately take up more space than bush plants, but they tend to yield more fruit, and their sprawling vines can often be tucked back close to the main plant. Given the limited amount of space they cover, both bush and semi-bush squash produce a lot of fruit, almost as if the plants don’t realize their short side vines are missing.

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

These compact winter squash are not, however, without drawbacks. Bush squash typically concentrate their fruit set at one time, leaving them susceptible to heavy losses from insect damage. With their single stem and minimal foliage, bush squash are particularly vulnerable to stem-chewing vine borers and leaf-feeding squash bugs (see Tip). Fortunately, semi-bush squash tend to set fruit in several flushes, giving the plants a chance to replace lost fruit after an insect onslaught.

Because foliage helps produce the sugars that feed the fruits, the small amount of foliage on a bush plant can contribute to poorer tasting flesh. The tendency of some bush varieties to overproduce fruit compounds the problem. But the best of them produce plenty of good-looking, tasty fruit.

Seven Compact Squash That Measure Up

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

‘Gold Nugget’, a bush buttercup, is my favorite bush squash because it has the strong squash taste I prefer. The fruits, which average 1 lb. to 3 lb., start out pale yellow and ripen to red-orange with faint striping. The flesh inside is firm, dry, and dark yellow. The fruits’ tough skin repels squash bugs and cucumber beetles, but the stems, like those of other buttercup squash, are highly susceptible to vine borers.

‘Emerald Bush Buttercup’ is often billed as a true bush variety, but in my experience, the plants start out as a tidy bush, then send out runners toward the end of the season. The fruits are pale gray-green, similar to those of most vining buttercups. Their skin is not as thick as that of ‘Gold Nugget’, so to prevent sun-scald and insect damage, harvest the fruits as soon as they mature.

‘Burpee’s Butterbush’ is the best of the bush butternuts. It produces small, uniform fruits that usually weigh less than 1-1/2 lb. each. ‘Burpee’s Butterbush’, like all butternuts, is highly resistant to vine borers because vine borer larvae have trouble chewing their way into the hard stems. This is an enormous advantage here in the Midwest and in the South. But you must be sure to thin some of the fruits; otherwise the plants will overproduce, leaving you with squash the size of a pickle.

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

‘Ponca’, a semi-bush variety, is an excellent butternut squash for gardeners with a little more space. The vines cover an area 6 ft. square, but more vines mean more full-size fruit. True to the butternut type, ‘Ponca’ fruits have tan skin, thick necks, and lots of light orange flesh.

‘Table King’ is a bush acorn variety whose compact plants are as vigorous as those of most vining varieties. The fruits mature in only 75 days, but taste much better if allowed to cure on the vine a few more weeks, until their bottoms turn orange. I thin to five fruits per plant, and if the plant is healthy, all will develop into full-size, full-flavored squash.

The best of the bush acorns is ‘Table Gold’, which is sometimes called ‘Golden Acorn’ or ‘Jersey Golden Acorn’. I find the orange-skinned fruits sweeter and more flavorful than common vining green acorns.

One of my favorite squashes, a relative of acorn squash, is ‘Sweet Dumpling’. This variety has a compact vine most of the season, but develops a larger vine toward harvest time. The green and white striped fruits are perfect for a single serving. Their flavor is richer, sweeter, and nuttier than that of other acorn varieties.

Healthy Squash Plants Produce Tasty Fruit

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

I don’t hurry to plant winter squash, because early plantings have a terrific fight against cucumber beetles. My last frost is about April 25, and although bush squash can be planted then, I wait until the third week of May, when the soil has warmed to above 70˚F.

Although I often direct seed my squash, I would recommend setting out transplants in a small garden, where you can’t afford heavy losses. Transplants tend to fare better against cucumber beetles, which love emerging seedlings. I set out my transplants when they have fewer than four true leaves, or else the plants will be stunted all season.

Most people plant squash in mounds of soil, known as hills, but I don’t bother because my soil is so sandy that the hills disintegrate with the first good rain. I start three seeds in one 2-1/4-in. pot, and then I plant the root ball with all three seedlings in one hole, a grouping I refer to as a hill for lack of a better word. If you prefer to start seedlings one to a pot, you can still plant three seedlings together in one hole; packed close together, they’ll help support each other when the wind blows. I space my hills roughly 3 ft. apart.

Photo/Illustration: David Cavagnaro

Winter squash are heavy feeders. The ideal soil for growing squash, whether bush or vining, is a smooth sandy loam with good drainage and lots of organic material. I prefer to feed my squash a mixture of manure and straw from my poultry pens, although I do use some 6-24-24 or 13-13-13 commercial fertilizer at times. Go easy on the nitrogen, though, or you’ll end up with foliage that could choke a horse, but no fruit.

Give squash 1 in. of water a week, but not too much moisture at planting time, or the seeds will rot. Mulch looks pretty and keeps squash fruit off the ground in a wet year, but I don’t mulch my plants, because mulch hides squash bugs, and its added moisture tends to induce rot in the plants.

The bottom line is that a healthy squash plant produces tasty fruit. This is because a stressed plant uses sugars to keep going, rather than to feed its fruit.

Hauling in a Full-Size Harvest

Bush winter squash should be harvested before the first frost, because squash subjected to frost don’t keep as well. To determine whether a winter squash is ready to harvest, poke the skin with your fingernail. If your nail leaves a mark, the squash is still immature. I never rush to pick a squash. Even if it looks ripe and passes the fingernail hardness test, I wait a week or two before harvesting it. Squash allowed to mature fully on the vine keep longer in storage.

After being picked, winter squash improve in flavor if allowed to cure for a week or two. Harvested fruits should be kept outside in a warm and sunny place for a few days, then stored in a dry indoor environment with a temperature of around 55˚F. The fruit from most compact winter squash plants keeps for three to nine months—butternuts the longest, acorns the shortest—so you can enjoy homegrown produce in the dreary days of winter.

Comments

Interesting. I was hoping to trellis vine squash for maximum yield. I didn't realise bush varieties are that compact. Thanks.

Hi Glenn: Very good suggestions. Thank you. You recommended "I start three seeds in one 2 1⁄4-in. pot, and then I plant the root ball with all three seedlings in one hole," "packed close together, they’ll help support each other when the wind blows." I really like this idea. Did you grow these vertically on a trellis? Don't you think the three seedlings are too crowded with at most 1-2-inch distance between them?

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in