What Is the Best Mulch? We Put Mulch Qualities to the Test

Learn what a university study discovered about the benefits of using mulch

Every gardener wants a gorgeous garden. Choosing the right plants for your site and using proper planting techniques are, of course, essential steps in establishing a successful landscape. Choosing the right mulch, however, can also be critical to the success of your plants over the years. Most gardeners have heard that mulch can improve plant growth, conserve moisture, reduce weeds, and moderate soil temperatures. But how much good can mulch really provide to plants, and is there any difference in the benefits among common mulches?

To answer these questions, my colleague Bob Schutzki and I did a comprehensive study at Michigan State University to track the effects on plants of various landscape mulches. Instead of just looking at their effect on plant growth, we also examined the impact on soil moisture, soil pH, weed control, and nutrient availability to determine the underlying benefits of mulch. We continued to monitor the impact of mulch for nine years. What we discovered from this study not only was interesting but also might help you decide if breaking your back to mulch each year is really worth the effort.

A proper test requires replication and strict monitoring

The study consisted of 24 landscape plots, which we set up in East Lansing, Michigan, in 2005. Within each plot, we planted ten 3-gallon deciduous and evergreen shrubs. After planting, we mulched the plots to a depth of 3 inches with one of four organic mulches commonly found at garden centers: ground red-pine bark, ground recycled pallets, hardwood-bark fines, and ground cypress mulch. Two additional plots in each replication were not mulched: One plot served as an unmulched control, and the other was kept weed-free by hand weeding and applying directed sprays of glyphosate. All treatments were replicated four times.

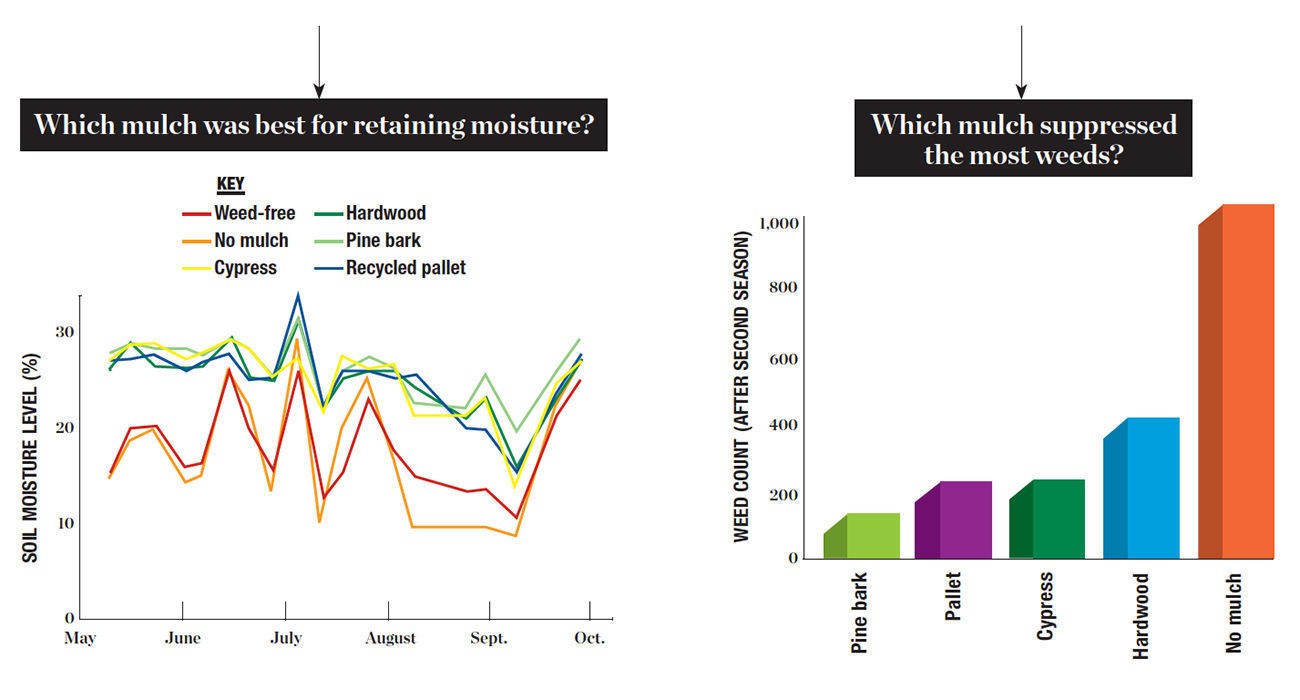

For two summers after planting, we monitored soil moisture at a 6-inch depth on each plot using a moisture gauge. At the end of the third growing season, we determined shrub growth (height and width), soil pH, and leaf nitrogen concentration in the shrubs. Researchers from the university conducted a weed assessment, as well. As part of a follow-up to this initial study, we also reassessed the height growth of the shrubs in 2013.

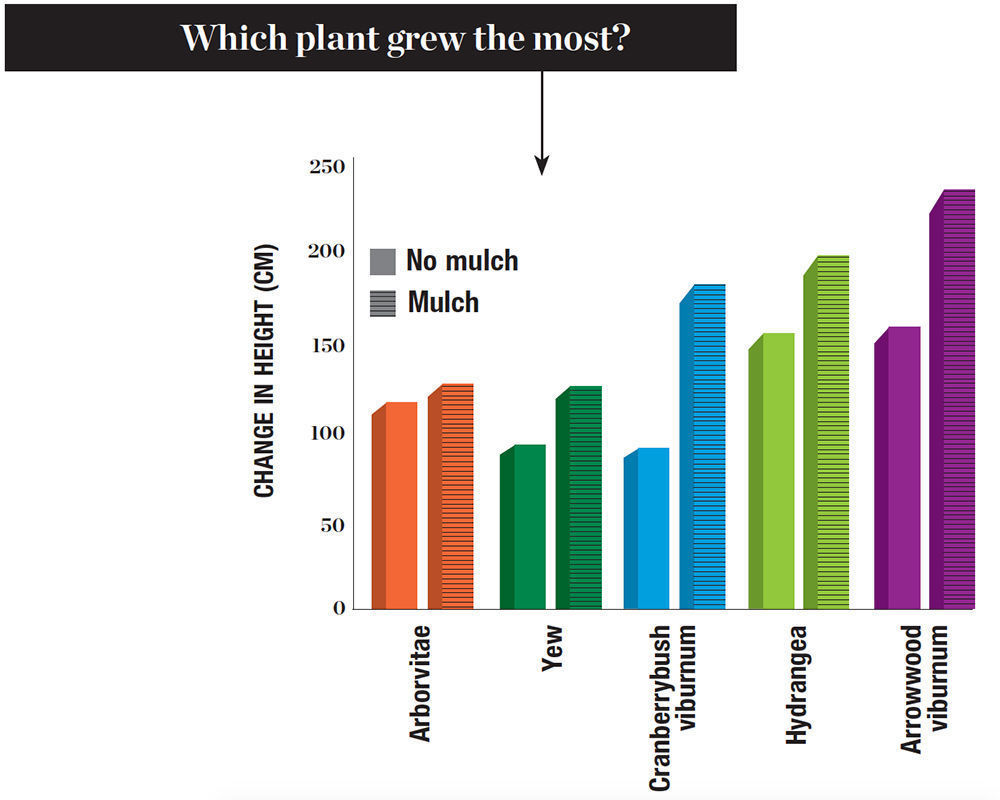

Improved growth and fewer weeds are just two benefits of mulching

When we conducted our initial assessment three years after planting, all of the mulches, except cypress mulch, increased shrub growth compared to the plots that did not have mulch or had just weed control. Growth rates of shrubs on the plots that were not mulched but where we controlled the weeds were basically the same as the plots where we didn’t do anything (no mulch, no weed control). Soil moisture followed a similar pattern as growth: Moisture availability was highest in the mulched plots, followed by the plots with no mulch but weed control, and then the plots with no mulch and no weed control. The amount of weeds present in the mulched plots was about one-quarter of that of the plots with no mulch and no weed control. There wasn’t a huge difference in weed control among the mulch types.

The results of this study show that mulching can improve the growth of plants by improving soil-moisture availability due to reduced weed competition and reduced evaporation from the soil surface. We did not observe a significant nutrient “tie-up” effect, which is often cited as a potentially negative effect of organic mulches with a high ratio of carbon to nitrogen. We found, in fact, improved foliar nitrogen levels with the plants in the mulched plots compared to the ones in the unmulched plots.

The growth and performance of the shrubs were similar overall, regardless of which mulch was applied. The exception to this was the cypress mulch, which suppressed growth compared to the other mulches. The reason for this is not entirely clear; soil moisture, pH, and foliar-nutrient levels did not differ between the cypress mulch and the other materials. Cypress wood contains secondary compounds that contribute to its resistance to decay but might also have allelopathic effects. Overall, however, it is clear that mulch provides significant long-term benefits to landscape plants compared to not mulching. This was especially apparent when we revisited the plots in fall 2013, nine growing seasons after planting. The plants that were mulched continued to have a significant growth advantage over unmulched plants. The bottom line is that mulch is worth the occasional backache.

But what about trees?

Recently, some have suggested that mulching has little or no positive effect on trees—in fact, some claim it is detrimental. We, however, conducted trials with trees that show clear benefits with mulching. In one study, we compared the growth of two different types of conifers with and without wood-chip mulch. After six years, mulching increased stem-caliper growth by 15 to 19 percent.

More recently, we tracked the growth of 48 London plane trees (Platanus × acerifolia, USDA Hardiness Zones 4–8). We mulched half of the trees with a 3-inch depth of ground pine bark, while the remaining trees were left unmulched. After two growing seasons, the stem caliper of the unmulched trees increased by 9.4 mm, whereas the mulched trees increased in caliper by 15.9 mm.

Know the Basics of Mulching

Spreading mulch is one of the simplest and most effective ways to get trees and shrubs off to a good start and to keep them healthy and growing. Mulching also helps protect trees from “lawn-mower blight” and “string-trimmer trauma.” Here are some tips to help you get the most out of mulch:

Apply a 2- to 3-inch-deep layer of mulch. Most of the benefit in terms of soil-moisture conservation, temperature moderation, and weed control can be achieved by putting down a thickness of 2 to 3 inches of mulch. More mulch probably won’t hurt, but it won’t help either.

Top-dress every year. Doing so will help you maintain a desired depth and appearance.

Avoid using grass clippings as mulch. Besides being unsightly and smelly, grass clippings can mat together and cause water to run off. Compost your clippings first, then apply them to your garden or landscape beds.

Use the “doughnut” technique. When mulching trees, leave a diameter of a few inches of soil unmulched around the base of a tree to avoid piling mulch against tree trunks and causing damage.

Bert Cregg is an associate professor of horticulture and forestry at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

Photos, except where noted: courtesy of Bert Cregg. Charts: Abigail Lupoff.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in