How a Plant Gets to Market

Getting informed about the green-goods supply chain can help you understand why plants aren’t dirt cheap

Why should you care where your petunia comes from? The best reason is that knowing the basics behind any consumer-goods supply chain leads to a better understanding of cost and quality. Many of us might complain about the price of that hydrangea shrub (Hydrangea spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 4–9), but there are years of development, marketing, and breeding that need to be accounted for (i.e., paid for) once that shrub hits nursery shelves. In my many years of university teaching, research, and extension, I’ve interacted with every level of the plant supply chain: from breeders, to propagators, to growers, to retailers, to gardeners. I’ve educated students that have become employed by each and every sector, allowing me to “look behind the curtain” numerous times. These experiences have given me a better understanding of how plants make their way from thousands of miles away, through many hands, in and out of several businesses, to my local garden center’s doorstep.

Learn more: How Market Growers Made Gardening Their Business

Plant breeders come in all shapes and sizes

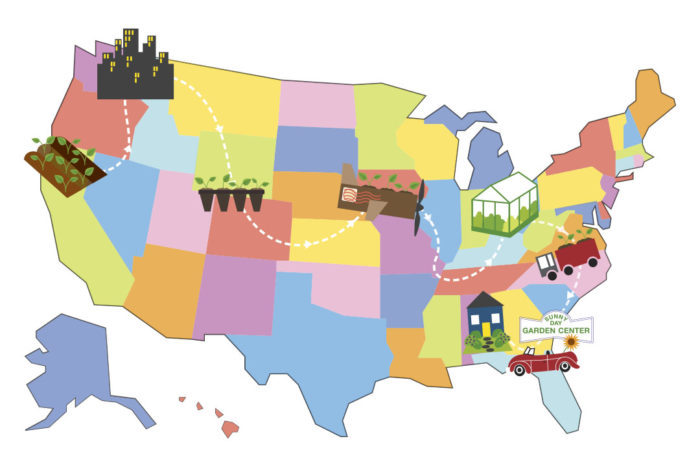

The road from a cutting or seed packet to a nursery or garden center can be extremely

direct or have many steps: plant breeders, breeder agents, propagators, finishing growers, and retailers. And for every new plant introduction, there is a different path taken that might include some or all of these steps. Plant breeders are some of the most knowledgeable folks in the world regarding the particular taxa they are working on. You can’t change the blossom color, for example, of something that you don’t completely understand. Plant breeding is an international effort. Breeders may be individuals or persons associated with a large enterprise, such as a seed company (e.g., Ball Horticultural Company).

Not all plants, however, are specifically bred. Many favorite cultivars are naturally occurring sports or mutations picked out of a large population by an eagle-eyed propagator or by nursery growers—like Steve Lighty and Angela Treadwell-Palmer, who discovered the cultivar ‘Little Joe’ Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium dubium ‘Little Joe’, Zones 3–8) while working at the Conard-Pyle Company. Gardeners have made their own contributions as well. Donald and Rozanne Waterer spied an unusually large and vigorous hardy geranium in their garden and introduced it, through Blooms of Bressingham, as Rozanne geranium (Geranium ‘Gerwat’, Zones 5–8). It is now one of the top-selling perennials in the world.

It’s important to realize that plant breeding is not a speedy process. The quicker a plant becomes reproductive, the more babies can be made. This sounds perfectly reasonable for petunias, but woody plants can take much longer—years, or even decades in the case of trees—to flower, set seed, germinate, and grow out the next generation. Plant breeding, therefore, is a lifelong passion and effort.

Show me the money: A tale of plant promotion

Plant introduction and promotion firms—or plant-breeder agents—can help independent

breeders (or gardeners with their random discoveries) with trials, the patenting process, and marketing. Think of them as sports agents for plants. Plant-introduction companies can arrange performance trials, if the breeders haven’t already done so. They can create marketing materials, help with patenting paperwork, and facilitate the collection of royalties. They also promote the plant to propagators and growers. There is a tremendous amount of internal, business-to-business marketing that the gardening public never gets a whiff of—and all of that costs money.

Plant patenting, introduction, and promotion can, indeed, be handled by the breeder, but a specialized firm can make it go faster and easier, allowing breeders to do what they do best: facilitate plant sex. Some plant-introduction entities are nonprofit collaborations among breeders, public gardens, and academic institutions. These partnerships specialize in plants that have proven to be great performers in a certain region. For example, Plant Select, Denver Botanic Gardens, Colorado State University, and the green-industry (landscape, nursery, and greenhouse) associations of Colorado have joined forces to promote tough, adaptable, water-wise plants for the Mountain West. At the other end of the spectrum are the big boys—like Proven Winners (PW), with its worldwide trial sites, breeder networks, and promotional/advertising muscle. Having a plant selected and promoted by PW is the horticultural equivalent of your kid being picked in the first round of the NBA draft (and about as likely).

Making more plants can happen locally or abroad

Once a plant is bred/discovered and gains a good reputation and patenting thanks to marketing, someone needs to grow the gobs of plants that the public will inevitably demand. The propagator produces seedlings (called “plugs”) or rooted cuttings (called “plugs” or “liners”) and then sells flats of these to a finishing grower. How many times have you heard or read the phrase “Plant propagation is both an art and a science”? Well, it’s true. Propagation on a commercial scale takes special facilities, knowledge, and more than a little experience.

5. Finishing. This step involves folks who specialize in growing a plug (left) into a salable plant. They will pop the rooted cuttings out of their small cells and repot them into larger containers (center). The finishing grower then cares for the plant for as long as it takes to get it sized up (right).

Some companies keep stock plants in Central America and either root the cuttings at rooting stations in the United States or sell unrooted cuttings to other propagators or finishing growers. Some companies only propagate. Large greenhouses or nurseries sometimes have a propagation section, where they propagate plants for themselves as well as for sale to other growers. Small volumes of plugs are boxed and shipped via UPS or FedEx; larger amounts are palletized and flown or trucked to their next destination. Most propagators are wholesalers; they do not sell directly to the public. Also, propagators must be licensed to propagate patented plants legally.

Look for the truth in the advertising

Plant marketers do a lot of good—like bringing our attention to fantastic plants, such as Rozanne geranium, that could have been lost forever in obscurity. But the hype surrounding the advertising of some plants is, well, overstated. Look for these overused terms, and be aware of what they really mean when you’re reading the tag or catalog description of the next best thing. “Long blooming” For flowering annuals, you can expect continual bloom (maybe encouraged with a snip here or there). That’s what they’re bred to do: bloom themselves silly until frost or extreme heat ends the party. But “long blooming” or “perpetual blooming” is not quite the same for perennials and woodies. “Everblooming” roses or even “repeat blooming” daylilies aren’t going to be smothered in blooms for the entire growing season. “Hardiness” Most hardiness marketing info for a plant errs on the side of caution, yet we all push boundaries and feel victorious if we manage to gain a zone or two. But severe winters, such as the one in 2014, are a slap back to reality; I lost many Zone 7 treasures in my Zone 6 garden. “Disease resistant” You need to remember that the key here is disease resistance, not immunity. I have yet to meet a bee balm (Monarda didyma and cvs., Zones 4–9) that didn’t get powdery mildew at some point, regardless of its purported resistance. |

The finishing touch is yet another step

Finishing growers pot up plugs, liners, or bareroot plants; place them in containers in a nursery or greenhouse; and grow them until they are a marketable size and at a specific stage of bloom (if applicable). Cell packs of annuals can be finished in a few weeks. Perennials take two to six months or more, depending on whether they require vernalization (a chilling period). Shrubs and trees might take multiple growing seasons. The inputs needed to get these plants to a desired size include growing media, fertilizer, water, and, of course, labor. The longer a plant is in production, the more labor is involved, especially with woody plants—pruning, pest and pathogen management, fertilizer application, and repotting to larger containers. If the finishing grower is also a retailer, the gardener purchases the plant directly from the company. If a wholesale grower finishes the plant, it must be shipped to a retail destination. This could be a big-box store or an independent garden center.

The path through this complicated network might be different for each plant. A Supertunia® from PW may hit every step of the network from Japan to Ecuador to Michigan to Virginia; a local retail greenhouse grower might keep a stock plant of ‘Arp’ rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Arp’, Zones 8–11) out back, propagate it, and sell it directly to gardeners. But most often, there are many hands involved in the process and a lot of time, which all leads to higher costs. After all that, $10.99 for a 1-gallon perennial doesn’t seem that outrageous now, does it?

Holly Scoggins is an associate professor of horticulture at Virginia Tech.

Comments

When you feel bored and tired from continuous working then you must take a rest for the few times checkers games and refreshing your mind in some times.

The process of getting a plant from a farm or nursery to a market can involve several steps. First, the plants are grown and cared for by buy patents farmers or nurseries. Next, they are harvested and packaged for transport. Then, they are transported to a distribution center or directly to retailers. Finally, they are sold to consumers at a market or store. This process can vary depending on the type of plant, the location, and the specific market or retailer.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in