How to Easily Grow Potatoes in a Can

It isn’t crazy—there’s always space for spuds

No matter what type of gardener you are—be it vegetable, ornamental, or both—the space you have to grow your plants often dictates your choices. So as a gardener whose “garden” is actually a collection of containers on an 8-foot-long and 5-foot-wide balcony off of a second-floor apartment, I get my seed catalogs and often have to thumb heartbreakingly past my all-time-favorite edible: the potato.

The potato has it all: It’s easy to grow; requires little maintenance; and even produces beautiful, star-shaped flowers. It also yields an abundance of edible tubers that can be mashed, baked, scalloped, or fried, according to your taste.

For several years, I resigned myself to the idea that this tuberous plant was not suitable for a container garden. But where there’s a will, there’s a way. This year, I set all negativity aside and, with a little research and experimentation, decided that all I needed was the right container. And I found that in the most unlikely of places: the kitchen garbage can.

What you need

- Deep plastic garbage can

- Potting mix that is safe for edibles

- Drill, or hammer and nail

- Potato starts

Step 1: Prep the can

A. Potatoes need a soil depth of about 2 feet to grow in, so select a can that will accommodate that amount of soil. A plastic can is best because it is weatherproof and you can easily drill drainage holes in it. You also want to start with a clean can. If it’s new, simply wash away potentially harmful residues with warm water; for an older can, eliminate possible bacteria by washing out the can with warm, soapy water and rinsing it out with cold water to remove the suds.

B. Potatoes will rot if left to sit in wet soil, so drill several drainage holes in the base of the container. If you don’t have a drill, you can improvise by using a hammer and nail to pound out several holes. Make sure you drill holes in the base as well as along the sides—about 1 to 2 inches above the bottom—to ensure plenty of drainage.

C. Once you create the drainage holes, place your can in a sunny location and fill it 5 inches from the top with potting mix. If the soil level is lower than that, the container rim may shade the potatoes, preventing them from getting enough sunlight; if it is much higher, you will not have enough room to mound soil on top of the emerging plant. Potatoes prefer slightly acidic soil but will perform well in almost any soil. For ease of movement and drainage, you can place the can on a rolling plant stand or on pot feet.

Step 2: Plant the potato

A. Press your potato starts about 6 inches into the soil with the eyes facing toward the sun. Plant only one or two starts per can; otherwise, the soil will quickly be sapped of nutrients. Cover the starts with the soil.

B. Because the potato tubers will grow in the soil that lies between the surface and the original potato start, it’s important to mound additional soil on top of the emerging plant. Remember to leave some green foliage above the soil line so that the leaves can photosynthesize. You may have to mound soil on the plant a couple of times in the early stages of growth.

C. If the potatoes make their way to the surface after a few weeks, then their exposure to direct sun will cause the greening of uncovered potatoes, leaving them bitter and potentially toxic. To fix that, add more soil to keep them covered as they grow.

Step 3: Keep the plant alive

Potatoes require minimal care under mild conditions. During warm weather, however, be sure to keep the soil in your container moist. Avoid overwatering, which will cause potatoes to rot; it can also produce watery, gritty potatoes. I generally water my potatoes once a week; I water more frequently during extreme heat or periods of drought. After the plant has grown a few inches tall, I also like to apply an organic fertilizer that is safe for edibles. This is the only round of fertilizer I use. Too much fertilizer will produce a large, lush potato plant but few tubers.

Step 4: Let the foliage expire

If you are an impatient person, like me, harvest the small baby potatoes, referred to as new potatoes, as soon as the plant finishes flowering. Once the flowers are gone, the plant’s energy is completely invested in growing tubers. As the plant starts to turn yellow and die back, dig down and gently harvest a few potatoes to test their size. People willing to wait the full term for tuber maturity will know it’s time to harvest when the potato plant dies back completely.

Step 5: Dig up the harvest

A. In a limited space, it’s good to keep the mess to a minimum. Lay down some newspapers or a tarp, and simply dump out the contents of the can. Sift through the soil with your fingers to locate the tubers.

B. Once you’ve harvested all the potatoes, dispose of the soil and the expired plant. The nutrients in the soil are gone, and it may harbor disease, so don’t reuse the soil or put it in the compost pile. Wash the potatoes, and allow them to air dry before storing. Harvested potatoes can be kept in a cool, dark location for several months.

Growing Tip: Double your start

You can purchase potato starts from almost any nursery or garden center from late winter to early spring. Another option is to prepare your own starts. Keep some potatoes from the grocery store or farmers’ market, and let them sprout at home. Any potato with eyes (the sprouts that emerge when you’ve left a bag of potatoes sitting in a drawer too long) is able to be planted and will grow under the right conditions. If a potato start has more than one eye, you can cut the potato in half and let it dry out to form two potato starts.

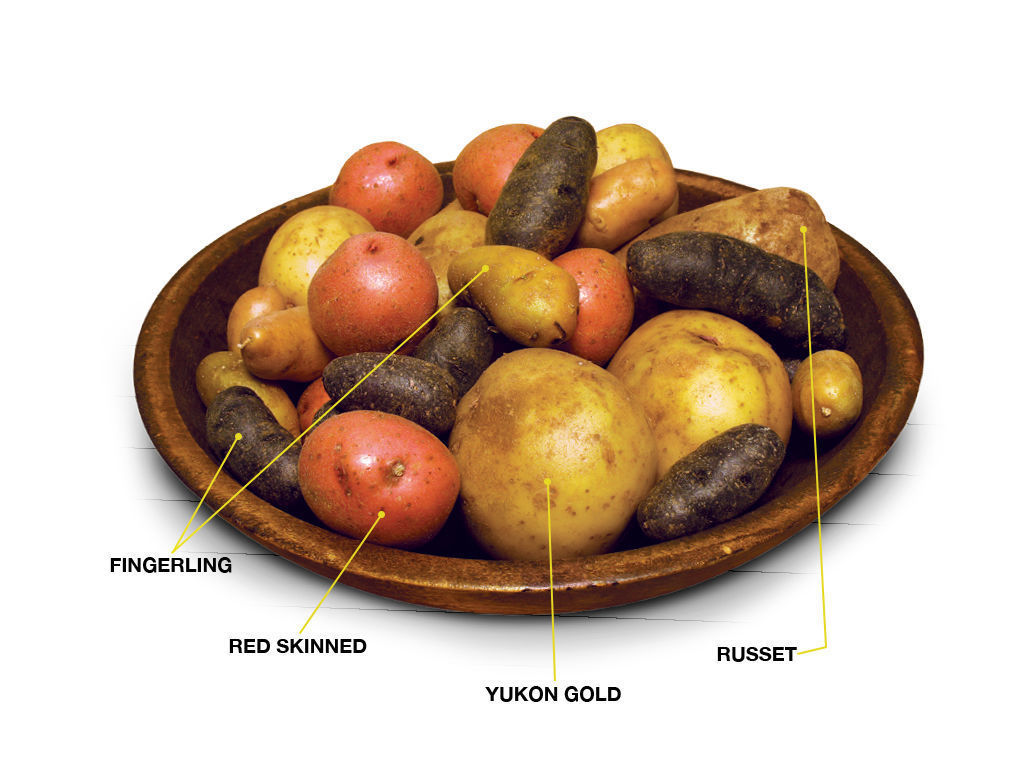

Potatoes for every meal

When planting potatoes in a can, you’re working with limited space. To get the maximum enjoyment out of your harvest, start by picking and planting a potato variety that best suits your taste. The starch content often dictates the best use of the potato variety: High-starch content is typically described as “gritty” and has a crumbling and fluffy texture, medium-starch content is often creamier and multipurpose, and low-starch content holds together more readily and has little or no grit.

Fingerling: Low in starch. Use: roasted potatoes, steamed potatoes, boiled potatoes

Red skinned: Low in starch. Use: potato salads, gratins, fried potatoes

Yukon Gold: Medium starch. Use: baked potatoes, mashed potatoes, soups

Russet: High in starch. Use: baked potatoes, French fries, potato pancakes

Brandi Spade is an assistant editor.

Photos, except where noted: Kerry Ann Moore, Brandi Spade

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in