How to Attract Good Bugs to Your Garden

To lure beneficial insects, first identify the players, then give them the right habitat

It happens every spring. First, a few aphids appear on the cold crops. I barely notice. A week later, the aphids have doubled. I start to get concerned. After another week, the number has grown again. Should I panic? Reach for the soap spray? Will my helpers come to my aid again this year? And then, one morning, there they are, lady beetles wandering among the aphids, dining contentedly. In a few days, there’s hardly an aphid to be found. I’m always amazed that the lady beetles come in such numbers, and at the right time. And they always do the job.

My garden consists of numerous vegetable beds surrounded by a diverse border of annual and perennial flowers, herbs, and fruit trees. Next to the garden are wild areas where some of the less troublesome weeds grow to maturity. And among the vegetable beds are plots of alfalfa, clover, and buckwheat. In these places dwell a militia of beneficial insects, ready to emerge to eat or parasitize other insects that may be harmful to my plants. On a warm summer day, I can see a light haze of tiny parasitic wasps visiting the fennel flowers in search of nectar. The nectar will sustain them while they look for aphids or caterpillars in which to deposit their eggs. It’s a relief to have such formidable allies. I haven’t needed even an organic pesticide in 15 years.

Build a safe and welcoming environment

We’re living in a bug-eat-bug world. And I want to keep it that way. To do so, I’ve transformed my garden into an insectary, a habitat where my beneficial-insect friends will feel at home. I provide them with food, water, and shelter. I keep the soil covered with organic matter. And I avoid putting any harmful chemicals into their habitat.

The menu for beneficial changes constantly as the pest population shrinks and swells and as different flowers come into bloom. Many of the predators and most of the parasites will use pollen and nectar for food. I try to sustain them throughout the year by growing a variety of flowers that bloom at different times. Because many of the beneficials are tiny or have short mouthparts, I offer them tiny flowers.

Start luring beneficials quickly with annuals, such as sweet alyssum (Lobularia maritima) and zinnia (Zinnia spp. and cvs.). At the same time, set out perennial flowers and herbs, including yarrow (Achillea millefolium and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 3–9), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare and cvs., Zones 4–9), and tansy (Tanacetum vulgare, Zones 4–8). Beneficials are also fond of the flowers of parsley (Petroselinum crispum and cvs., Zones 5–9); when you’ve finished harvesting this herb, leave it in the garden to flower. I like to let a small patch of carrots run to flower, too. Their blossoms are fragrant, and beneficials love them.

I intersperse insectary plants with my vegetables. I figure if the target pests are close to the pollen and nectar source, there is a greater likelihood the beneficials will find them. If you add to all this a patch here and there of alfalfa, buckwheat, or clover (all quite attractive to beneficials), you’ll be well on your way to establishing an arsenal of insect allies. Your garden will be healthier and safer because of it.

I water my garden with overhead sprinklers so that insects always have puddles and wet leaves to drink from. If I were using drip irrigation, I’d offer them water in a saucer filled with pebbles so they wouldn’t drown. Beneficials need protection from heat and rain. They need to hide from birds and insects that would make a meal of them. Again, leafy plants offer protection. Ground beetles hide in low-growing ground covers and in mulch or leaf litter. Flying insects hide in shrubs, on the undersides of leaves, and even among the petals of zinnias.

Beneficials also need a reason to stay on when they’ve finished cleaning up the crops or at the end of the season when you’ve cleaned up the garden. Consider re-creating in a corner of the yard or on the edge of your garden the thick, wild diversity of a hedgerow by using a variety of early-flowering shrubs, perennials, and grasses to provide year-round shelter and a place for alternative prey to dwell. Keep this beneficial-insect reservoir as close to your garden as you dare.

Use strategies that sustain beneficials

Insect allies hate dust. Keeping the soil covered at all times—either with mulch or with growing plants—conserves moisture, moderates temperatures, and eliminates dust. It also provides a habitat for ground and rove beetles. Don’t eliminate every weed; leave some for the insects.

If you use selective insecticides to rid yourself of pests, you run a strong risk of ridding your beneficials of prey, as well, even if you’re using relatively benign products, like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) or other biologicals. Nonselective pesticides could rid you of beneficials altogether. I believe there’s no place in an insect habitat for these chemicals.

When you abandon chemical control for biocontrol, you may experience a sudden increase in pests. It may take a while for the beneficial-insect population to expand to the point that you can relax your guard. In the meantime, I’d rely on less harmful botanical and natural controls to slow down the bad guys until the good guys show up.

Creating a habitat for wild insects is an imprecise activity. With experimentation and observation, you may hit on the right combination of plants that encourages the right combination of insects for your garden. Your success will probably vary from year to year as the climate and vegetation change and new pests arrive. You should expect the development of a habitat where pests and beneficials exist in a rough balance to be an effort of several years rather than a season or two. Despite the presence of so many beneficials in my garden, I still find myself, from time to time, having to handpick squash bugs or to rub scale from the branches of fruit trees.

It’s mid-October, and the cabbage is covered with whiteflies. If I shake a plant, a fluttering cloud rises from the waxy leaves. A few hoverflies move among the plants, depositing eggs on the leaves. With the lens in hand, I turn over each leaf and look closely at the mass of whitefly eggs, nymphs, and adults. A few hoverfly larvae are feeding on the whiteflies. I notice that a couple of larvae have already pupated. New hoverflies will emerge in a few days and begin looking for pollen and nectar. A large Asian lady beetle is grazing through the crowd. I guess I can relax. It looks like the insects have this outbreak under control.

Get to know the cast

To create a welcoming habitat for your insect helpers, first, you need to know something about them. A good way to start is to grab a hand lens and a picture book of insects and take a rough census of your resident population. If you’ve avoided using pesticides and have a variety of plants growing, you may find many allies already present. The ones you’re most likely to see include lady beetles, ground beetles, lacewings, hoverflies, a couple of true bugs, and a few tiny wasps. These can be divided into two groups: those that eat their prey directly (predators) and those that deposit their eggs on or into their host (parasitoids).

Hoverflies: With their striped abdomens, hoverflies look like small bees, but they move through the air more like flies, zipping from plant to plant, hovering briefly before landing. The hoverfly, or syrphid fly, is one of many predatory flies and the most conspicuous beneficial bug in the garden. I can find them just about anytime anywhere. They visit a variety of flowers in search of pollen and nectar, and they lay their eggs near aphids or other soft-bodied insects. The eggs hatch into hungry larvae that eat up to 60 aphids per day.

Lacewings: When the fairylike green lacewing flutters silently by in search of pollen or nectar, I find it hard to imagine it in its fiercely predacious larval stage, during which it devours aphids, caterpillars, mealybugs, leafhoppers, insect eggs, and whiteflies. It even eats other lacewings. Up close, the larva looks like a tiny (½-inch-long) alligator.

|

|

|

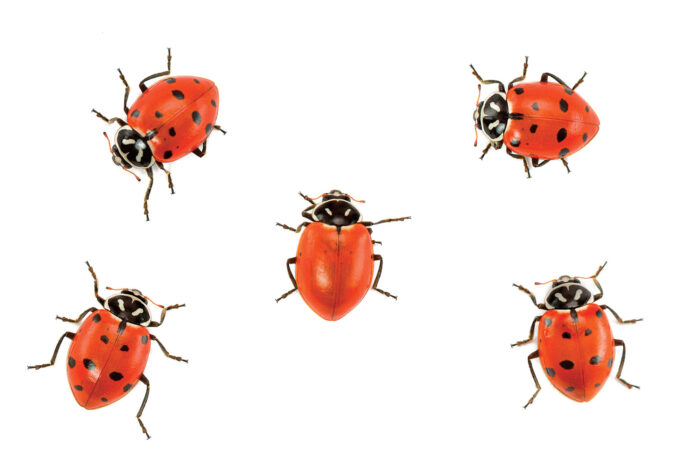

Beetles: The two kinds of beetles that are most helpful are lady beetles (aka ladybugs) and ground beetles, both predators.

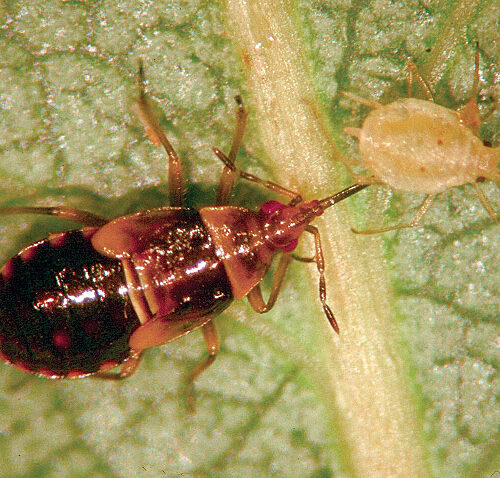

Lady beetles prey on aphids and other soft-bodied insects. The adults will eat as many as 50 aphids per day. If you have enough aphids and the beetles stick around long enough to lay eggs, each hatched larva (above right) will eat some 400 aphids. There are many species of lady beetle that attack many different preys.

Ground beetles don’t fly much, preferring to run away when disturbed. You probably won’t see them unless you uncover their hiding places. If I see them at all, it’s when I’m picking up old piles of weeds. They’re relatively large (about ¾ inch long) and dark, with long, jointed legs. They’re nocturnal hunters, rooting among leaf litter for insect eggs and larvae.

|

|

Parasitic wasps: These helpful creatures, ranging in size from minuscule to small, will defend your garden against caterpillars like corn earworm, tomato fruitworm, cabbageworm, and tent caterpillar.

Parasitic wasps: These helpful creatures, ranging in size from minuscule to small, will defend your garden against caterpillars like corn earworm, tomato fruitworm, cabbageworm, and tent caterpillar.

The smallest and perhaps most popular parasitic wasp is the trichogramma wasp, a dust particle–size creature that lays up to 300 eggs in moth or butterfly eggs.

Braconid, chalcid, and ichneumon wasps are much larger than trichogramma wasps, and they parasitize caterpillars directly, laying eggs in or on the caterpillar. The hatching eggs eventually either kill the host or disrupt its activities. Braconids parasitize aphids, as well. If you’re scouting with a hand lens and notice some mummified aphids with neat circular holes in them, you’ll know a braconid was there.

True bugs: There are bugs—and then there are true bugs. True bugs, such as the minute pirate bug and the big-eyed bug, belong to the insect order Hemiptera. Many are plant feeders, but others are predaceous, with tubular mouthparts they insert like a straw to suck the juices out of their prey.

The minute pirate bug is a tiny (3 mm) predator with a wide-ranging appetite; it eats aphids, thrips, mites, whiteflies, and insect eggs. It lays its eggs on the leaf surface near its prey; nymphs hatch and begin feeding. The cycle from egg to adult takes only three weeks.

The other important true bug is the big-eyed bug. It’s a little bigger than the minute pirate bug and has a similar diet. It also eats nectar and seeds, so it may stay even if it can’t find an insect to eat.

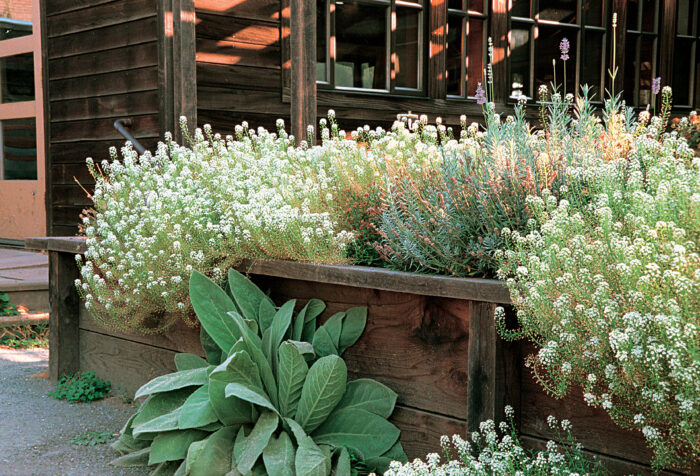

Beautiful plants attract beneficial insects

A mix of annual and perennial flowers provides alternative food sources for beneficials when prey insects are scarce.

Sweet alyssum: A big planting of this fragrant annual offers season-long nectar and a perfect haven for lots of beneficials.

Fennel: The tiny flowers of umbelliferous plants, like fennel, are especially attractive to lacewings but also to hoverflies, parasitic wasps, and lady beetles.

Tansy: In addition to hoverflies, these yellow button flowers attract lady beetles, lacewings, minute pirate bugs, and parasitic wasps.

Zinnia: The flat blossoms of zinnias make a good insect landing pad, and the shallow nectar-bearing flowers are easy for beneficials to drink from.

Yarrow: Grow nectar-bearing plants near your edible crops. Here, white yarrow grows beside arugula.

Common chicory: Even weeds can attract beneficials. Chicory (Cichorium intybus, Zones 4–8) is a common roadside plant and a favorite of hoverflies.

Parsley: Don’t be in a hurry to pull out this herb at the season’s end. If you allow it to stay over winter, then the following year, its flowers will provide food for good insects.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in