A Secret Recipe for Great Homemade Potting Soil

Adding compost or garden soil can help you create the best mix

I work hard to ensure that the soil in my garden is the best I can give my plants, and they reward me with robust health. Yet that same good soil if transferred to a container would cause the plants in it to languish. That’s because garden soil doesn’t offer enough air, water, or nutrients to a plant growing in a container. Potting soils are specifically formulated to overcome these limitations. Below, you’ll see what needs to be in the soil mix to ensure that your container plants have the nutrition and structure they need. Plus, see Lee’s recipe for a homemade potting soil that will allow you to experiment with what works best for your plants in your area.

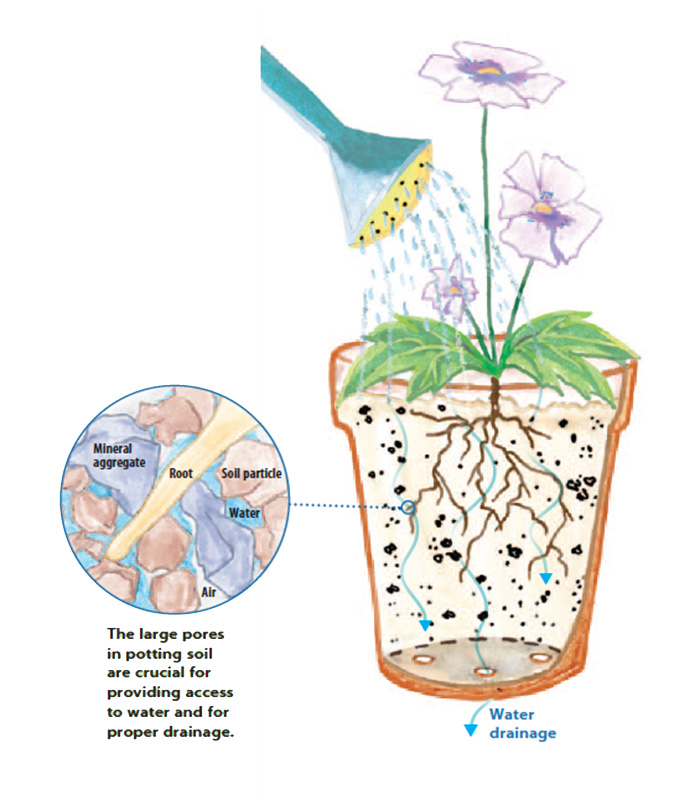

Potting soil needs to drain well but still hold moisture

One of the most important things a potting soil needs to do is provide roots access to air by letting water drain away from them. In the ground, the soil is usually deep enough to let excess water drain beyond root zones. In pots, however, water tends to accumulate at the bottom, despite drainage holes. The smaller the pore spaces of the soil in the pot, the higher that water layer will reach. Larger pores, formed by adding mineral aggregates to potting soils, readily admit water into the soil, then carry it through the medium and out the bottom. Then all those large, empty spaces can fill with air.

Perlite, vermiculite, calcined clay (kitty litter), and sand are the mineral aggregates most commonly used in potting soils. Perlite and vermiculite are lightweight volcanic rocks naturally filled with air. I prefer perlite over the others because it does not decompose with time nor lose its aerating ability if the potting mix is compressed. Vermiculite is a valuable additive because it prevents some nutrients from leaching away, and it even provides a bit of potassium and magnesium.

A potting mix also must have ingredients that help it retain moisture. This is where organic materials—usually peat moss, sphagnum moss, or coir—come in. They cling to some of the water that the aggregates are helping to drain. Organic materials also hold on to nutrients that might otherwise wash away.

In addition to peat moss, vermiculite, and perlite, commercial mixes often contain sawdust or various grades of shredded bark. Lime may be added to help balance the acidity of the peat moss, and a small dose of fertilizer can often make up for the lack of nutrients.

Adding compost or garden soil can be beneficial

Most gardeners make potting soil by combining perlite or vemiculite with peat or sphagnum moss. Two other organic materials that you could add to your potting mix are leaf mold and compost, which offer a wide spectrum of nutrients.

Adding some garden soil to a homemade potting mix contributes bulk while buffering against pH changes and nutrient deficiencies. The reason that garden soil is rarely added to commercial mixes is because of the difficulty in obtaining a steady supply that is consistent in quality and free of toxins such as herbicide residues.

Soilless potting mixes are relatively free of living organisms, but mixes made with soil or compost are not. Some gardeners talk about “sterilizing” their potting mixes by baking them in the oven to rid the soil of harmful organisms, limiting the hazards of damping-off and other diseases. What I hope they mean is that they “pasteurize” their mixes. Heating homemade potting mixes to sterilizing temperatures wipes out all living things, beneficial and detrimental, leaving a clean slate for possible invasion of pathogens and causing nutritional problems such as ammonia toxicity. Pasteurization, which occurs at lower temperatures, kills only a fraction of the organisms. The best way to pasteurize your soil is to put it in a baking pan with a potato embedded in the soil. Bake it at 350°F for about 45 minutes. When the potato is cooked, the potting mix is ready.

I don’t pasteurize my potting mix. I rely instead on healthy container-gardening practices such as timely watering, good air circulation, and adequate light to avoid disease problems. Beneficial microorganisms in compost and garden soil also help fend off pests.

TIP: Customize your mix to suit your plants

Whether you use a manufactured or homemade potting mix, it’s a good idea to have extra mineral aggregate and organic materials on hand to suit some plants’ special needs. I add extra aggregate for plants that like their soil on the dry side. I add extra peat moss to my mixes for plants that prefer constantly moist soils. I grow top-heavy plants in a mix amended with calcined clay or sand to add weight to the pot.

Lee’s recipe for homemade potting soil

I’ve found that making my own potting soil produces better results than commercial mixes and eliminates the need to monitor my containers’ nutrient and pH levels. With plenty of good soil in my backyard, I have no trouble making this traditional potting medium. It features a mixed bag of ingredients, but I figure that plants, like humans, benefit from a varied diet. This mix can support plants for a year or two without additional fertilization.

Mix 2 gallons each of:

- peat moss

- perlite

- compost

- garden soil

with 1/2 cup each of:

- dolomitic limestone

- soybean meal

- greensand

- rock phosphate

- kelp powder

I place a ½-inch mesh screen over my garden cart and sift the peat moss, compost, and garden soil to remove any large particles. I then add the remaining ingredients and turn the materials over repeatedly with a shovel, adding water if the mix seems dry. After a few incantations, the stuff is ready to work its magic on everything from my tomato seedlings to my weeping fig.

Make your own soilless mix

Years ago, Cornell University scientists came up with a formula for a soilless potting mix, which forms the basis for many commercial potting mixes on the market today. By following this recipe, you can easily replicate what is sold in bags at the garden center.

Ingredients

1 bushel peat moss

1 bushel perlite or vermiculite

½ pound dolomitic limestone

1 pound 5-10-5 fertilizer

1½ ounces 20% superphosphate fertilizer

Mix the ingredients thoroughly. The mix is initially hard to wet, so moisten it as you stir it. This saves the trouble of doing so each time you remove some for use.

Lee Reich is a soil scientist who gardens in New Paltz, New York.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in