Garden Troubleshooting: Is Your Soil the Problem?

Learn how to spot, diagnose, and treat soilborne diseases

One by one, your prized tomato plants wilt and die, or clumps of your brightly colored pansies (Viola spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 4–8) collapse into scraggly brown mounds. At first you might assume that your drooping plants have gotten too much or too little water. You also need to consider the strong possibility that pathogens, or disease-inducing microorganisms, are living in your garden’s soil and are now attacking your carefully tended plants.

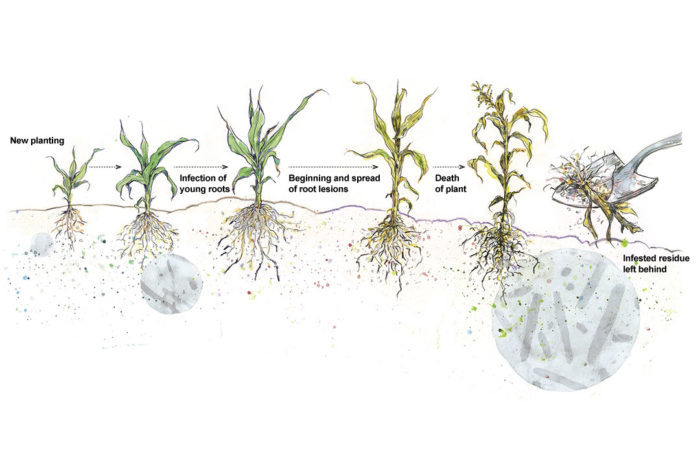

Some of the most challenging issues facing gardeners are soilborne diseases (infections and subsequent diseases in plants caused by pathogens that live in the ground). Hiding invisibly in the soil, these pathogens—most of which are fungi—lie in wait until a suitable plant host is placed within reach. Then they invade the plant, colonize its roots and stems, and cause bad things to happen to the plant victim.

Knowing what’s at stake can make you a better gardener

So how do these soilborne pathogens arrive in your garden in the first place? Many soilborne pathogens are endemic, with naturally occurring populations already living in the ground almost everywhere. These unwanted guests, however, can also arrive in your garden in one of two other ways: on foreign soil or on new plants. Flooding can bring contaminated soil from elsewhere; you might amend your planting area with soil or compost that contains invisible pathogens, or you might use tools or equipment encrusted with infested soil. These pathogens can also lodge themselves inside a plant. Strawberry transplants, artichoke divisions, and asparagus crowns can harbor soilborne pathogens. In rare cases, some of these pathogens can even invade seeds.

Why worry? First, no gardener is immune to losses from soilborne diseases because they can affect every cultivated plant species. Even native vegetation growing in the wild has soilborne enemies. Not only is the list of belowground adversaries extensive but also each plant species is susceptible to multiple attackers. Tomatoes, for example, can die from any of eight pathogens found in the ground. Second, soilborne diseases can cause extensive damage to the whole plant—and even to an entire crop. A soilborne pathogen attacks the essential connection between plant and soil: the roots and crown. When those parts are compromised, the plant often wilts and then collapses and dies. A third reason for concern is that the pathogens causing these diseases are capable of long-term survival. Designated by researchers as “soil inhabitants,” these microorganisms can live in soil for many years, even when their favorite plant hosts are absent.

Look for these signs

Just as symptoms in a patient can aid a doctor in determining a person’s illness, symptoms in a plant can help a gardener deduce if a soilborne pathogen might have made the plant sick. Be on the lookout for the following issues:

- Darkened, soft, and rotted roots

- Discolored and rotted crowns

- Discoloration of the internal (vascular xylem) stem and root tissues

- Wilted leaves, shoots, and flower stems

- Defoliation (or leaf loss)

- Stunted growth

- Reduced numbers of flowers or fruit

- Overall poor or disappointing growth

- Death of the plant, especially if the disease is in an advanced stage

A few practices can limit the damage

In many situations, you can manage the formidable challenges of soilborne diseases by using three control strategies: planting resistant varieties, using chemical fungicides, and employing effective cultural practices.

The most effective measure against soilborne diseases is to find and use plant varieties bred to resist pathogens. There are certain celery varieties, for instance, with excellent genetic resistance to the fusarium yellows pathogen. Unfortunately, not all plant species have resistant varieties.

You can combat certain seed and seedling soilborne diseases by purchasing and using seeds treated with chemical fungicides. This isn’t a viable option if you are growing organically, however. Fungicides applied to plants already in the ground do not sufficiently control most soilborne problems, and studies indicate that biological-control products, which contain living organisms or organic by-products, are not consistently effective against soilborne diseases. Research shows, for example, that the beneficial microorganism Trichoderma reduces disease severity under controlled experimental conditions; however, when used in the field or garden, the reduction in disease is inconsistent.

Certain cultural practices can help plants avoid contact with pathogens, reduce the number of bad microorganisms in the soil, and create environmental conditions that discourage disease development. Make every effort to place your plant in garden areas that have no history of soilborne diseases that affect that type of plant. To prevent spreading pathogen-infested dirt, clean your equipment and tools when moving from one area of the garden to another. Also, it’s a good idea to practice crop rotation by not replanting the same crop or plant species in the same area year after year. Each time a susceptible plant is grown in soil that harbors the pathogen, that pathogen will reproduce on the infected host, resulting in escalating populations in the soil. Switching to nonhost plants will prevent this pathogen increase from happening in that location.

Be cautious, as well, when sourcing plants. Investigate your seed sources to check whether the seeds, which can carry certain pathogens, have received certification that they are pathogen-free. Avoid planting transplants that might be contaminated or infected. Well-meaning neighbors might offer you artichoke crowns dug out of their garden, but such crowns might already carry diseases. And finally, place plants in soil that drains well. Pathogens often need overly wet soil conditions to infect and cause disease. Drip irrigation enables greater control over water delivery, resulting in better water management, reduced soil saturation, and a lowered risk of some soilborne diseases.

Soilborne diseases: The major players

Although a plant pathologist is the only person capable of making a completely accurate diagnosis, gardeners with a keen eye can often determine if they have a soilborne disease based on the symptoms a plant exhibits.

Crown and root rots

Discolored, rotted roots; darkly discolored crown tissue

An extremely broad category of disease, crown and root-rot problems can affect both external crown tissue and internal crown tissue (photo). Eventually all the foliage wilts and collapses. This category also includes early transplant die-off. Crown and root-rot pathogens include the bacterium Erwinia and the fungi Fusarium, Macrophomina, Phytophthora, Pythium, Rhizoctonia, Thielaviopsis, and many others.

Plants affected: Virtually all ornamental, vegetable, and fruit species

How to control it

- Place plants in soil that drains well.

- Avoid shallow planting holes for perennials, trees, and shrubs.

- Steer clear of species that are particularly sensitive to overwatering and root rot, such as Indian hawthorn (Rhaphiolepis indica, Zones 8–11).

Damping off

Water-soaked, soft, rotted roots and main stems, brown to black in color

Some plants such as spinach (photo) are especially sensitive to damping off. In preemergent damping off, the pathogens attack and kill seeds and newly germinated seedlings before they have the chance to break through the soil surface. Postemergent damping off occurs when seedlings emerge successfully from the soil but then wilt and collapse quickly. The most common causes of damping off are the fungal pathogens Aphanomyces, Fusarium, Phytophthora, Pythium, Rhizoctonia, and Thielaviopsis.

Plants affected: Germinating seeds and young seedlings

How to control it

- Delay seeding until temperatures warm up; damping off is often more severe during cold, wet times of the year.

- Plant seeds in soil that has good tilth and aeration and that drains well.

- Use seeds treated with a protective fungicide, if possible.

- Avoid planting seeds too deep.

- Irrigate carefully so that the soil is not overly wet for long periods.

- Consider using transplants for species known to suffer from damping off.

Vascular wilts

Poor growth; stunting; wilting or dying foliage

If a plant appears to suffer from a lack of hydration or nutrients (photo above), you might have vascular wilt. You can get further confirmation by cutting into the vascular (xylem) tissue inside the main stem and taproot; such tissues will look notably discolored, with brown to black streaking (photo right). The fungal pathogens Fusarium and Verticillium are the principal causes of vascular wilts.

Plants affected: Woody ornamentals and some vegetables

How to control it

- Plant resistant varieties; plant breeders have developed tomato cultivars that resist verticillium wilt, fusarium wilt, and nematodes (labeled “VFN tomatoes”).

- Place plants in locations in which previous plantings have not shown signs of wilt.

- Avoid spreading contaminated dirt to other areas, as Fusarium and Verticillium can last in the soil for many years.

White mold, southern blight, and other sclerotial fungi

Discolored crown tissue; wilting

If you notice the gradual collapse of plant tops (photo above), you might have white mold or southern blight. This category of soilborne pathogens consists of fungi that form survival structures (sclerotia) that are usually some shade of brown or black. Sclerotia range in shape from spherical beads (photo right) to long seedlike structures.

Plants affected: Herbaceous ornamentals, vegetables, and turf

How to control it

- Place susceptible plants in uninfected areas, as resistant varieties are not available.

- Avoid moving contaminated dirt to clean areas so that you do not spread the sclerotia around your garden.

Armillaria root rot and other wood rotters

Poor growth; leaf drop; death of limbs and branches

Slow-developing armillaria root rot and other wood rotters often begin as root infections; the pathogens slowly colonize the roots leading up to the crowns and main parts of the plant. For many types of wood rot, you’ll expose a whitish mycelial membrane when you cut beneath the bark. In other cases, the white mycelium or other fungal structures will form on the outside of the bark. Additionally, Armillaria sometimes will form mushrooms at the base of infected trees and shrubs during the winter season (photo above). Other wood-rotting pathogens include Ganoderma, Oxyporus (also known as Poria), and Phellinus.

Plants affected: Trees (both ornamental and fruit) and shrubs

How to control it

- Replace dead plants with resistant varieties.

- Avoid spreading contaminated dirt to clean areas of your garden or property.

Steven T. Koike is a plant pathologist with the University of California Cooperative Extension in Monterey County who researches diseases of edible and ornamental plants.

Photos: courtesy of Steven Koike. Illustrations: Elara Tanguy.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in