An appropriate space to interview a man who has spent his life advocating for the preservation of native ecosystems might be a meadow buzzing with pollinators or a forest edge teeming with birdsong. Unfortunately, when you’re also trying to record such an interview for posterity, a quiet conference room at the University of Delaware is the better choice, and that is where we sat down with Douglas Tallamy, PhD, professor of entomology and wildlife ecology to discuss his research into the impact of nonnative plant species on the environment.

Perhaps due to the courtroom-like surroundings, there was an anxious tension in what Dr. Tallamy had to say. This was understandable because in some ways the fight to curb habitat destruction is one of the biggest cases of our lives. Tallamy has emerged as a star witness in this case, with his fieldwork and research playing a critical role in solving the mystery of the plummeting insect and bird populations seen over the past 50 years. Despite the seemingly larger-than-life problems we face, Tallamy insists there are ways average gardeners can help save our ecosystems.

Listen to an extended audio version of this interview via our podcast: Episode 120: An Interview with Doug Tallamy

Should gardeners be planting only native plants?

You can have a landscape comprised of 100% native plants and still support little because you’ve chosen natives that don’t make a lot of food. Natives good, nonnatives bad? It’s not nearly that simple. Nothing in the world is black and white. With almost everything I say, there’s an exception. I do talk in generalities, but I think the biggest contribution our lab has made is the discovery of the keystone species concept.

Can you explain that concept and why it’s so important?

First, you need to realize that you’ve got to support caterpillars. Who’s supporting the caterpillars? Just a few plants. Only 5% of our native plants support 75% of those caterpillars. And that’s anywhere—not just in my yard, but anywhere. And 14% of our native plants support 90% of the caterpillars. So I think of plants that support caterpillars as the two-by-fours in the ecological house we’re building. They’re essential. Your house will fall down without them. These keystone plants are supporting a functional food web.

Why focus on caterpillars specifically?

Most vertebrates do not eat plants directly. They eat invertebrates that eat the plants, and most of those invertebrates are insects. And most of these insects are caterpillars. So caterpillars are transferring more energy from plants to other animals than any other type of plant eater. You can look at the health of an ecosystem by knowing how healthy your caterpillar populations are—how many caterpillar species there are and how many there are of those species.

We need the pollinators to keep the flowering plants around, and we need the caterpillars to take the energy that plants capture and deliver it to other animals. And we need those plants and animals because they run the ecosystems that support us. So it’s not just about saving other species, although that’s fine. It’s about saving us. The more diverse an ecosystem is, the more ecosystem services it produces, and the more stable it is.

A study found that several species of native butterflies would be extinct without nonnative plants. Does that mean larvae are adapting, and if so, is that a good thing?

We should instead ask, “Why is this happening?” It’s because the native plants these butterflies rely on have been wiped out. Fortunately, their native plants were closely related enough to some nonnative ornamentals so that the butterflies could use them too. It’s just like the black swallowtail here on the East Coast that uses [nonnative] parsley and dill. That butterfly’s native host plants are members of the carrot family, which are not common here anymore. So the butterflies recognized that these nonnatives are in the same family of plants they eat. And not only that, but they taste good.

But these are exceptions. I will not say that adaptation is not happening. It’s certainly happening. And it means in those cases there has been a role for nonnatives. But if you took away all the native plants and just had nonnatives, you’d have a reduction of 88% of the species of moths and butterflies in the country. And we’ve got the research paper to show that.

And it’s a problem if people shift focus to the exceptions, right?

Yes, without focusing on the rule. The rule is that most of the time, you’re going to lose things by eliminating natives. How many species are eating ginkgo? How many species are eating crape myrtle? How many species are eating burning bush? Almost none.

But what about benign plants like hosta? Should gardeners remove those and replace them with natives?

Can gardeners have functional food webs without getting rid of all their nonnative plants? Yes, they can. Are hostas going to be major wreckers of ecosystems? No, they’re not. It’s not the presence of nonnative plants that destroys food webs; it’s the absence of native plants that does. Going back to the house analogy, you can’t build a house out of wallpaper. It doesn’t work. So how many two-by-fours do you need? Anything will be better than nothing.

So don’t grow only hostas. What about lawns that are just a monoculture of only grass?

Every landscape has to do four things: First, it has to support pollinators, because we need pollinators everywhere. Second, it has to support a food web, because we need functional ecosystems with all the animals that run those ecosystems everywhere, not just in our parks and our preserves. Third, it has to manage the watershed. Everybody lives in a watershed. Nobody has the ethical right to destroy that watershed, not that anybody sets out to do that. But the way you landscape determines whether you’re helping it or wrecking it. Fourth, it has to sequester carbon. That’s what plants do.

If you’ve got four acres of lawn, lawn does none of those things that a landscape needs to do. Lawn wrecks the watershed, supports no pollinators, supports no food web, and is the worst plant in terms of sequestering carbon. Anything else is better.

Notice that I didn’t say get rid of the lawn. I say you should reduce it.

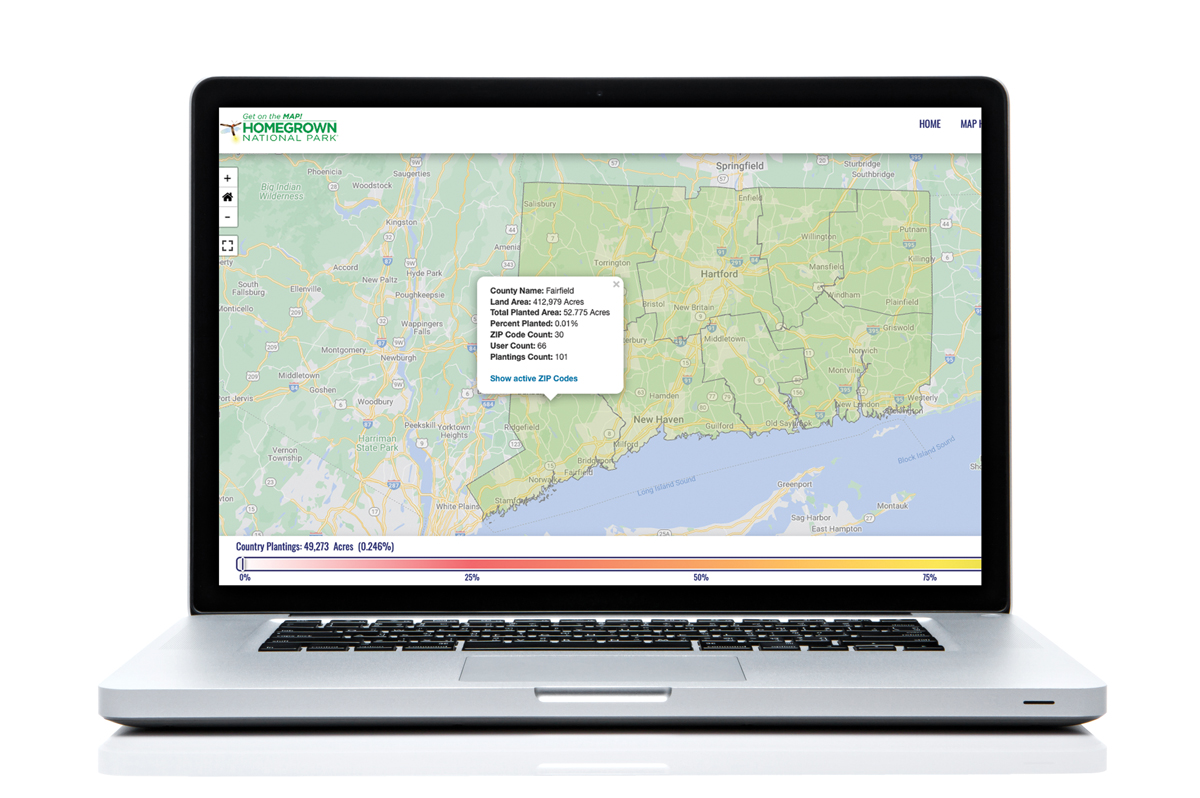

What is Homegrown National Park?

I got that idea when I heard the statistics about how much lawn we have—and this comes from a 2005 NASA estimate from satellite imagery—but it’s 40 million acres. That’s the size of New England dedicated to lawn, which is an ecological deadscape.

What would happen if we cut that area in half? That would give us 20 million acres for conservation. How big is that? More than most national parks combined. So I said we can create a new national park by planting native plants and removing invasive plants from our properties. It’ll be the biggest national park in the country. And if we do it at home, we can call it Homegrown National Park.

The concept is working; you can watch a map light up on the website (homegrownnationalpark.org) and see if you’re succeeding or not. You can see the biological corridors fill in. You can say, “Oh look, there’s a blank spot. I live there. I can help.”

You mention that white oak (Quercus alba, Zones 3–9) is your favorite tree. Why?

The hosta sitting there is taking up space, but not that much space. If you have an oak tree in the yard, it’s contributing a lot of plant biomass that’s helping a lot of creatures. Nationwide there are 952 species of caterpillars alone that eat oaks. And an oak tree will easily make up for the fact that your hosta is not doing anything. Think of your hosta as a little plastic statue. It’s there and it’s not wrecking anything; it’s just not helping anything. So how many plastic statues do you want? That’s up to you.

Keystone plants to support wildlife

According to Tallamy, “Gardeners need to recognize that their little piece of the world is part of the future of conservation.” And he sees that recognition as empowering. One person can shrink their lawn. One person can put in a pollinator garden. One person can take out their invasive plants. And, perhaps most notably, one person can put in keystone plants. These plants are massive ecological boons to the environment in the numerous species they support. If you’re looking to make a big impact on the health of your local ecosystem, consider incorporating these North American native plants into your landscape.

Top herbaceous plants

1. Goldenrod (Solidago spp., Zones 3–9)

2. Aster (Aster spp., Eurybia spp., Symphyotrichum spp., Zones 4–9)

3. Sunflower (Helianthus spp., Zones 3–9)

Top woody plants

4. Oak (Quercus spp., Zones 2–9)

5. Cherry (Prunus spp., Zones 3–8)

6. Willow (Salix spp., Zones 4–9)

7. Birch (Betula spp., Zones 3–9)

8. American elm (Ulmus americana, Zones 4–8)

9. Cottonwood (Populus spp., Zones 2–9)

Christine Alexander is the editor of FineGardening.com.

This interview was edited for length and clarity. For further reading, check out Douglas Tallamy’s most recent books, The Nature of Oaks (2021) and Nature’s Best Hope (2020).

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in