by Ruth Lively

October 1998

from issue #17

I fell in love with the names first: Black Gilliflower, Hubbardston Nonesuch, Knobbed Russet, Old Nonpareil, St. Edmund’s Pippin, Sops of Wine, Summer Rambo, and still my favorite, Westfield Seek-No-Further. Reciting them takes me on a journey across continents and centuries.

I’ve been fascinated with old apples for two decades, ever since I first got a glimpse of a Southmeadow Fruit Gardens catalog, offering “choice and unusual fruit varieties for the connoisseur and home gardener.” If the quaint names were what caught my attention, it was the descriptions that got me hooked. “The finest tasting apple in the world” (that’s ‘Cox’s Orange Pippin’), or “tender, spicy flesh…our first choice for tarts, pies, and compotes” (‘Calville Blanc d’Hiver’), or “so juicy it is impossible to eat without the juice running down one’s chin” (‘Summer Rambo’). Nobody was writing that kind of stuff about ‘Red Delicious’.

(Nearly) infinite variations on a theme

Another thing that intrigues me about old apples is that there are so many of them. And although the majority are red or at least partly red, there is a greater diversity in shape, color, and flavor than you can find in modern apples.

Four hundred years ago, the herbalist John Gerarde wrote, “The fruite of Apples do differ in greatness, forme, colour and taste; some covered with a red skin, others yellowe or greene, varying infinitely according to the soyle and climate. Some are sweet or tastie, or something sower; most be of a middle taste betweene sweete and sower, the which to distinguish I thinke it impossible.”

What varieties might Gerarde have struggled to distinguish? Certainly the aptly named ‘Queene’ apple, which was the most common variety during the Elizabethan age, and ‘Pearmain’, then considered the finest dessert apple. He would have eaten pies made of ‘Costard’ apples, the premier cookers of the day. And he probably knew the walnut-sized fruits of the ‘Lady’ apple, which then, as now, were used more for decoration than for eating.

Most apples we eat these days are consumed as snacks or lunchtime desserts. In centuries past, apples were enjoyed fresh too, but the vast majority were cooked, or dried, or turned into cider or vinegar or apple butter or applejack. People cultivated varieties especially suited to specific purposes. Fruits ranged from crisp to mealy, from very tart to thoroughly sweet, from juicy to dry, and each had its best use. If an apple’s skin was tough and waxy, or brown and roughened, it stored well because the skin prevented the flesh from drying out.

Today you’ll find a few old-timers at the store. ‘Golden Delicious’, ‘Jonathan’, and ‘McIntosh’ are widely available. But there’s not enough demand for most antique apples to make commercial production pay.

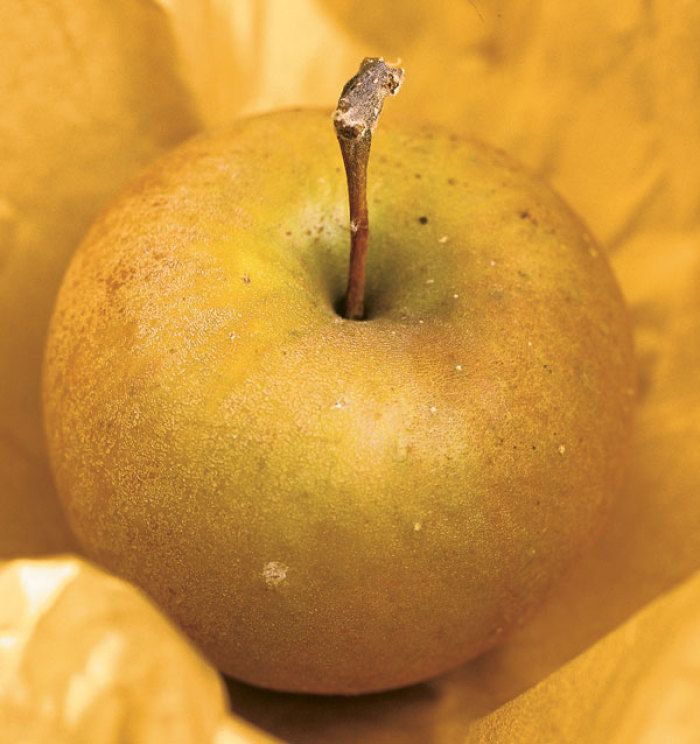

Take russet apples, for example, whose skins are spotted, patched, or entirely overlaid with a rough, leathery texture. You won’t find russets in the markets because they’re not considered pretty, but many have fabulous flavor.

For all their charm, old apples aren’t necessarily superior to modern ones. According to apple expert Tom Burford, plenty of old varieties were worthless. But the ones that have lasted owe their staying power to some good characteristics.

Culture tips

Grow antique apples as you would any other kind. They need full sun but only average soil. Trees take anywhere from 8 ft. to 25 ft. of room, depending on their eventual size (more about this under rootstocks). You’ll also need to prune your trees every year, sometime during the dormant season. Here are some other considerations.

You may have to work a little to keep your trees healthy. Apples are subject to several diseases, most notably scab, powdery mildew, and fireblight, as well as infestations of insects like codling moth, red mites, plum curculio, and certain kinds of aphids and scale. Varieties differ in susceptibility or resistance. Before choosing your apples, ask yourself how much imperfection and fruit loss you can tolerate, and figure out what your approach will be, should problems arise.

You may need a second variety for pollination. Although a few apple varieties can pollinate themselves, most are only partly self-fruitful, some are self-sterile but can pollinate other varieties, and a small group doesn’t produce any viable pollen at all. To ensure good fruit production, plant at least two varieties, and be sure their bloom time overlaps adequately. Most crab apples make good pollinators. If there are other apple or crab apple trees within a couple hundred feet whose flowers open at the right time, you may not need more than one tree. If you plant a triploid variety, such as ‘Bramley’s Seedling’, which has more than the usual number of chromosomes and is always pollen-sterile, you’ll need a self-fertile companion or multiple trees, or you’ll get fruit only on the triploid.

Some varieties bear only every other year. When they do fruit, these biennial or alternate-year bearers often crop so heavily they wear themselves out. In the off years, you may get only a few apples, or none at all. If a good harvest every year is important, choose annual bearers.

Most apples are snow bunnies. They grow about as far north as anyone would like to live, and south to the Gulf Coast, except for the Florida and Texas peninsulas. But like all hardy fruit trees, apple trees need to spend a certain amount of time at temperatures below 45˚F before they can break dormancy in spring. Chill requirements vary from 400 to 1800 hours. If you live in the warmer reaches of apple-growing country, Zones 7 and 8, buy varieties that need no more than 600 chilling hours.

The rootstock makes a difference. Big apple trees—even those of the antique varieties—are relics of times past. Nowadays, fruit trees usually come on dwarfing or semi-dwarfing rootstocks, which result in a tree that’s easier to care for and fruit that’s easier to pick. Dwarf trees grow 5 ft. to 9 ft. tall, and their root systems are similarly diminished. In fact, trees on dwarfing rootstocks don’t form big enough root systems to support themselves. They need some form of irrigation and always must be adequately staked or they’ll blow over. Semi-dwarf trees are better for home gardeners. They reach from 12 ft. to 16 ft. tall (although trees on the smallest semi-dwarfing rootstock could be kept pruned to about 10 ft.), and they need no staking once established.

Ripe for the picking

Apple season ranges from high summer right through to hard frost. In addition to enough chilling hours, be sure you have a long enough growing season to ripen the fruit. Very late varieties like ‘Arkansas Black’ and ‘Calville Blanc d’Hiver’ may not ripen in upper north central and northeastern locations.

I asked Tom Burford how you can know when an apple’s ready to pick. He warns against relying on the calendar to tell you when to harvest, because soil, weather, culture, and a tree’s age affect ripening times. Experience and observation are your best tools. “When you see the first windfall, then is your time for vigilance. Select an apple from the south side of the tree, one that’s growing on the outside. Cut it open and examine the seed color. Apples are fully ripe when their seeds are fully colored. Seeds vary from purple to black to brown to yellow, depending on the variety. If you don’t know the seed color of a variety, just keep picking and cutting, looking, and tasting, until you learn the apple’s characteristics. When the apple’s the way you like it, it’s time to harvest.”

Selecting your ancient beauties

Because old apples were often grown for specific purposes, consider how you want to use the fruit before choosing varieties (for help making selections, see A Dozen Antique Apples to Collect). If you want apples for eating fresh, look for varieties described as dessert apples. Cooking apples usually have high acidity combined with pronounced sugar. Some hold their shape; others melt down to sauce. If you want to make cider, look for juicy apples with high sugar and a fair amount of acid for balance. If your space is limited, go for one of the very good all-purpose apples like ‘Grimes Golden’, ‘Northern Spy’, ‘Summer Rambo’, or ‘Yellow Bellflower’. There are so many wonderful apples among the old varieties, your biggest problem is bound to be narrowing down your selections.

You don’t need a root cellar to store apples

Generally, the later an apple ripens, the harder its flesh and the better and longer it will store. Early-ripening apples have soft flesh and don’t store well. Pick apples you plan to store before they’re fully ripe, when the seeds are just beginning to color.

For best results, try to improvise conditions that imitate a root cellar’s cold, humid—but not damp—climate. There’s one slight complication—apples emit ethylene gas, which hastens ripening and, eventually, spoiling. Here’s an easy way to provide the right conditions: Store only unblemished apples. Pack them in plastic bags, close tightly, and punch several holes in the bag with your thumb. Closing the bags helps maintain humidity, and the holes allow ethylene to escape. Store the bags in your refrigerator crisper. You can also keep them in a styrofoam cooler in a cool place after first thoroughly chilling the fruit. An unheated garage works well even if outside temperatures drop to –10˚F because very slight freezing won’t hurt apples. Every week or so, open the cooler to check the apples and let accumulated ethylene escape

Sources

Check with local orchards and public gardens with apple displays for tasting events. Place tree orders in fall or winter for spring delivery.

Applesource

1716 Apples Rd.

Chapin, IL 62628

800-588-3854.

www.applesource.com

Sells harvested fruits by mail, August to December

Trees of Antiquity

20 Wellsona Road

Paso Robles, CA 93446

Phone: (805) 467-9909

www.treesofantiquity.com

Southmeadow Fruit Gardens

PO Box 211

Baroda, MI 49101

269-422-2411

www.southmeadowfruitgardens.com

Tree-Mendus Fruit Farm

9351 E. Eureka Rd.

Eau Claire, MI 49111

877-863-3276

www.treemendus-fruit.com

Sells harvested fruits at the farm and by mail; apples available September to December

If you become a devotee, you may want your own copy of APPLES: A Catalog of International Varieties, by Thomas Burford.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in