by John Bray

October 1997

from issue #11

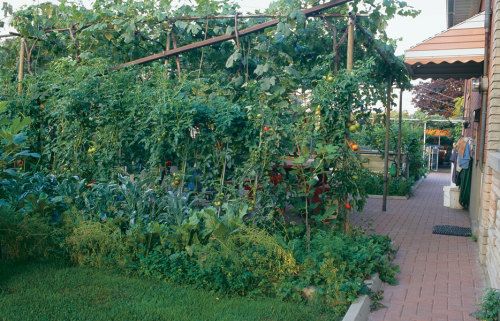

Don’t think of the corner of Ashmore and Rosewood as a mere intersection. Consider it a frame for an ornate kitchen garden tapestry. It wasn’t always so. Thirty years ago, when Joe Boccia and his wife, Maria, moved into No. 2 Ashmore in suburban Toronto, the compact brick house was bordered by a grass yard and a few elm trees. It was plain, nothing like the rich agricultural outskirts of Naples, Italy, their native land. They had come 6,000 miles in search of a better life through jobs in manufacturing. Their Italian farm community was out of sight, but not out of mind. Slowly, they brought down the elms, turned under the grass, and developed a garden of greens, colorful vegetables, and fruit trees, even figs. They have adapted and blended cultures.

Hybrid gardens take breeding

Joe has worked to tune his garden to the Canadian climate. In southern Italy, the weather was regular and reliable, as he puts it, “100%.’’ Who needed a cold frame? What serious gardener can do without one in Toronto?

Joe assembled a makeshift frame with scrap wood and plastic. The harbor shelters young plants for spring. And when the season fades, he moves in greens that keep through the early winter.

Still, in Ontario, Mother Nature can be a sly and heartless mistress. One mild, sunny October day, Joe’s vines were laden with tomatoes ripe for picking. Absorbed with preparations for a wedding, he put off the harvest. Frost struck that night and ruined the crop.

The ‘Niagara’ grapes, which Joe started from stock supplied by a friend in New York, are well suited for growing in the northland. One arbor shades a patio, while the other covers the driveway and neat stacks of firewood. From both drip dense green bundles of grapes.

Some things stay the same. You never saw bare soil on those southern Italian farms. It’s the same way in his garden now. Joe wastes no real estate. He trains and trellises, stakes and ties. All his garden rows are tidy and tight.

Endive, escarole, and chicory sprout in frilly, emerald lines. Radicchio is right nearby. So are the eggplants, some of which get picked when they are no bigger than your thumb. Sliced, the purple jewels add interest to salads.

Succession planting keeps the garden full. When the beans are done, the fennel goes in, and so forth for as long as the summer season lasts.

One variety is not enough for the fruit trees either. Three types of plums grow in the plum tree, and three types of pears in the pear tree, the result of creative grafting.

Nothing grows in the same place in the garden in consecutive years. “If you like meat, you can eat it every day,’’ Joe says. “But you like change. I think plants are the same way.’’

Yes, change in many things, but not when it comes to his prized ‘San Marzano’ tomatoes. Long and meaty, they float in a green lace of foliage draped on one section of the chain link fence. The tomatoes, distinctively Italian, are open pollinated with an indeterminate growth habit. They also are the primary ingredient in the spaghetti sauces Maria prepares.

So you have to wonder about the North American ‘Beefsteaks’ lolling conspicuously at one corner of the patio. Joe smiles. Those are for neighbors, who like the round shape for sandwiches.

By the light of the Toronto moon

No single piece of this horticultural fabric, no single thread or color seems unusual. Woven together, though, Joe’s garden presents a striking image, in terms of aesthetics, economy, and productivity.

Joe has no formal gardening training. People still seek him out.

“You don’t know how many people come here for seeds,’’ Joe says. “I give them some, and a year later they say, ‘Hey, why don’t my vegetables look like that.’’’

Success in the garden is no game of checkers. Chess is more like it. Joe plants only after the full moon. He mulches with grass clippings and bean hulls. He brings in manure, some from the rabbits he keeps. He does the work.

“My father learned from his father, I learned from my father. I don’t know the book. I know my experience.’’ But sons don’t always adhere to their father’s teachings. When his father came to live with him in Toronto, he saw that Joe was staking every tomato plant instead of training them on wires running between stakes, the practice on Pompeian farms. Joe shrugs, “Here is here; there is there.”

An elderly woman pushing a grocery cart walks by. Maria, seated under the patio arbor, looks up from the squash blossoms she’s arranging in a basket. “Buon giorno,” she calls. And those 6,000 miles don’t seem such a long way.

Gardens in the ashes

The roots of the Boccias’ Italian garden in Toronto stretch not only across an ocean but down 20 centuries to ancient Pompeii on the Bay of Naples. The great eruption of Vesuvius in a.d. 79 left houses and clear outlines of gardens perfectly preserved under 50 ft. of volcanic ash. Murals painted on house and garden walls and botanists’ analyses of casts taken from impressions left in the ashes by charred and decayed plant roots indicate what grew in those gardens. So we know grapevines and fruit trees were as beloved in Pompeian city gardens as in Joe Boccia’s.

Grape vines not only shaded city gardens, but bearded Vesuvius right up to the volcano’s mouth. Those slopes continue to support lavish vineyards, including those that produce the grapes for the region’s best known wine, Lacrima Christi.

Favored trees in Pompeii included almond, peach, pomegranate, pear, quince, apple, and cherry. Pliny the Younger wrote of citron trees grown in pots, and excavators have found that Pompeii’s gardeners also tended potted lemon trees. The evidence tells of gardens with culinary herbs and flowers. And there were large vegetable gardens with crops including beets, artichokes, beans, and asparagus. Pompeii was famous for its cabbages, considered a luxury in those days. The region’s reputation for excellent vegetables continues today.

One item an ancient Pompeian gardener visiting Joe Boccia wouldn’t recognize is the famous tomato from Pompeii’s neighboring village of San Marzano. Tomatoes weren’t introduced to Italy from the New World until the 16th century, but they were soon embraced by the Italians and now the San Marzano region produces what many believe are the world’s best sauce and paste tomatoes.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in