Every summer, I pull weeds from the gravel under our deck, and last summer was no exception. First, I pulled the big weeds, then I began pulling the smaller ones. It was starting to take time, so I grabbed a bottle of organic herbicide, whose active ingredient is 20 percent acetic acid (concentrated vinegar), and started spraying.

After about a minute, I noticed something hopping erratically in an area that I had just treated. I took a step closer and noticed that I had inadvertently sprayed a young frog. I asked my wife for a bowl of water and quickly washed off the frog. But it was too late; my careless spraying killed the poor critter.

Every chemical—including acetic acid—has benefits and drawbacks. To avoid synthetic herbicides, some people choose organic herbicides, believing that they are safer. But as you can see from my experience, this is not necessarily true.

Of all the herbicides on the market, there is perhaps none so widely used—or as vilified—as Roundup. Roundup works as a weed killer because it contains the active ingredient glyphosate, which kills plants by preventing production of an amino acid necessary for plant health. Other herbicides, such as KleenUp and Imitator Plus, also contain glyphosate.

Glyphosate has been accused of everything from killing aquatic life to poisoning humans. Some of these claims might be true, while others might be exaggerated or not supported by evidence. Let’s take a look at a few of the most common claims so that you can decide whether glyphosate-based herbicides are a good choice for you.

Tip: Whether synthetic or organic, use all herbicides with care – The use of any herbicide should not be taken lightly. The best choice for weed control is to hand-pull weeds and use organic mulch. If you choose to use an herbicide, however, and you are careful to follow the directions on the label, then a glyphosate-containing brand may be a reasonable choice for killing weeds if the product is used judiciously.

Claim 1: Glyphosate will end up in your drinking water

Glyphosate has been found in groundwater where large quantities are used for agriculture. Denmark restricted the use of glyphosate in 2003 because the levels in the groundwater were considered unsafe. There is, however, a distinction between using a small amount of glyphosate in a garden and using a large amount in agriculture. Applying a lot of glyphosate to soil can lead to small amounts of glyphosate in groundwater. Using a glyphosate-containing herbicide to kill a few weeds in your backyard is not likely to contaminate wells because there is simply too little chemical applied.

Claim 2: It builds up in the soil

When glyphosate is applied to plants, some will inevitably get into the soil. But the chemical binds rapidly to small particles, which inactivates it. In other words, the binding stops it from producing toxic effects. Glyphosate can last six months or more in soil before it disappears. It is generally considered to be immobile in the soil, but this isn’t always the case.

Claim 3: The chemical is poisonous to people

You may have heard that glyphosate is toxic to humans. Glyphosate is, actually, one of the lower-toxicity chemicals we use in the garden. It is less toxic than many organic pesticides, such as bordeaux mix (which is a combination of copper sulfate, lime, and water) and pyrethrins (botanical insecticides derived from chrysanthemum flowers). Most of the information we have indicates that glyphosate isn’t dangerous if you use it according to the directions on the label.

Claim 4: Synthetic herbicides kill aquatic life

Yes, synthetic herbicides can kill frogs. But it is most likely the inactive ingredients in the herbicides that kill them, not the glyphosate. Rick Relyea, a researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, found that Roundup killed tadpoles when it was present in ponds. Even a relatively small amount of Roundup or any other glyphosate-containing herbicide with its corresponding inactive ingredients could hurt aquatic life, so you should avoid spraying it near open water, like a pond, stream, or lake.

Tackling the Tough Questions on Glyphosate

Are the inactive ingredients in synthetic herbicides the real culprits?

On the bottle of every pesticide is a list of active ingredients, including glyphosate. Although they do not appear on the label, there are other ingredients in herbicides that help the spray to stick to and become absorbed by the leaves. These chemicals are called “inactive ingredients” or “adjuvants,” and without them, glyphosate would not be effective. Unlike active ingredients, which must be listed on pesticide labels, inactive ingredients are rarely listed. In the case of glyphosate-containing herbicides, some scientists believe that these adjuvants—such as POEA (polyethoxylated tallowamine)—may be more toxic than the glyphosate itself. One study showed, in fact, that herbicides with POEA had toxic effects on human cells that exceeded the effects of glyphosate alone.

What about a recent paper that claims that glyphosate is the most damaging chemical on Earth?

A paper was recently published in the journal Entropy that purportedly demonstrates that glyphosate is “the most biologically disruptive chemical in our environment.” In the authors’ words, glyphosate contributes to “most of the diseases and conditions associated with a Western diet, which include gastrointestinal disorders, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, depression, autism, infertility, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.” The authors did no original research; they, instead, collected and compared numerous articles to conclude that glyphosate affects human health. Most scientists find the article to be full of flaws, in large part because the authors connected the dots in a weak way. At the end of the paper, they encourage “more independent research to take place to validate the ideas presented.” That is exactly what the authors presented: ideas that have not been validated. What has not been presented is any real evidence that glyphosate causes the problems the paper suggests.

The Consequences of Spraying Glyphosate

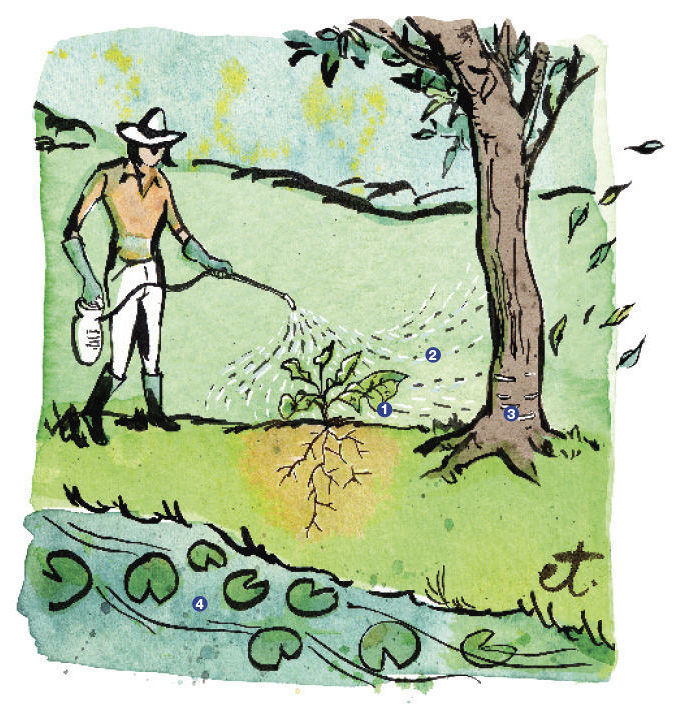

Spraying glyphosate has consequences; other wise, use of the chemical would be futile. This illustration depicts the results of spraying the intended plant and some of the results of spraying too close to waterways or plants you want to preserve.

1. Glyphosate inhibits proteins that plants need

The chemical becomes absorbed by leaves and is translocated throughout the weed and inhibits the formation of amino acids necessary for growth. Without these amino acids, the weed will die.

2 Applying glyphosate when the wind is blowing will lead to drift

Avoid spraying the chemical near valuable plants.

3. The chemical may enter the trunk or stems of damaged trees, causing harm

Be careful when spraying glyphosate near trees that have lenticels (small openings on the bark of woody plants) or that have been damaged by weed whackers, pests, or diseases.

4. Glyphosate can hurt aquatic creatures

Unless it is specifically labeled for that purpose, the chemical should never be used around ponds, lakes, streams, or other bodies of water.

Jeff Gillman, author of The Truth About Organic Gardening, is an associate professor of horticulture at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in