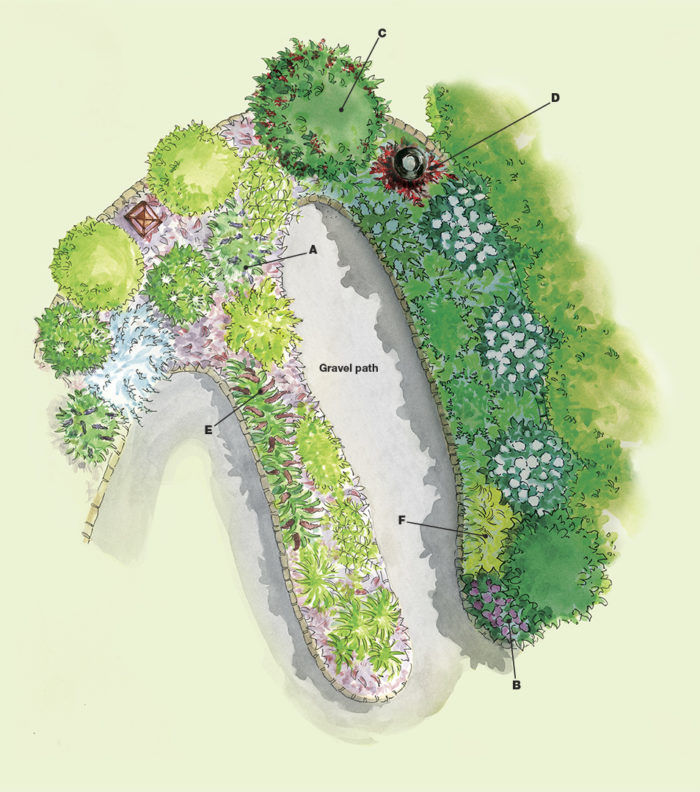

Seldom do large gardens fall into one exposure category. Most beds get a mix of sun and shade and everything in between. If you’re like many gardeners, when you have a new garden to landscape, you go to the nursery, fill up your cart with whatever excites you, then arrive home having no idea how to make sense of it all. This approach will certainly get your garden planted, but the new bed could look like a chaotic mishmash. So how do you make a garden look unified when you need to use plants that have extremely varied sun requirements? In the backyard of her home in Knoxville, Tennessee, Faye Beck has solved this design dilemma.

A year after moving into her house, Faye identified a spot in the backyard that would be perfect for a garden. But the space, which bordered a large tree line, stretched from full shade into full sun. To ensure that this large garden didn’t end up looking like two different beds, she divided the space down the sun/shade line, filled only one side with plants, then found “twins” for the other side. The result is a beautifully varied yet consistent garden.

Dividing the Space Simplifies Plant Selection

There’s no sense in pretending that a bed with a mixed exposure is homogeneous. Those who try to use the same plants throughout the entire garden often find that their selections are never truly happy. The full-sun plants in shadier areas struggle to size up and seldom bloom well, and the full-shade plants forced into a sunnier spot burn and sometimes peter out completely.

Instead of fighting this losing battle, Faye split her potential bed space, separating the full-sun section from the full-shade section. To help her identify the line of exposure, she watched the space at different times of day and marked where the sun/shade line was from sunrise to sunset. This exposure will, of course, change depending on the time of year, but ideally, you should monitor the area and make the exposure-line determination at the height of the growing season.

Remember that this line is just an estimate. You can move the sun and shade boundary lines back by a few feet to make the middle ground bigger and to build in allowances for seasonal changes. Faye installed a gravel pathway down the exposure line in her garden, which clearly defined the boundary and also allowed access into the middle of the large bed. Dividing the space also eliminates the area of the garden that receives both sun and shade. Not having to deal with the partial-sun portion of the garden made Faye’s plant choices clearer. Some people find this “gray” area to be the trickiest spot to find plants for because plants generally prefer either a little more sun or a little more shade—and there usually isn’t a partial-sun or partial-shade section of the nursery to make shopping easier. Consider, for example, oakleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia, USDA Hardiness Zones 5–9): Most reference books list this plant as a lover of sun to partial shade, but if you give it a little too much sun, the foliage will burn. The only way to get this “no-plant’s-land” filled in is by experimenting and by accepting the fact that some plants will die and some will need to be moved. Taking that troublesome space out of the equation makes things much easier.

Make the Garden Cohesive by Finding Sun or Shade “Twins”

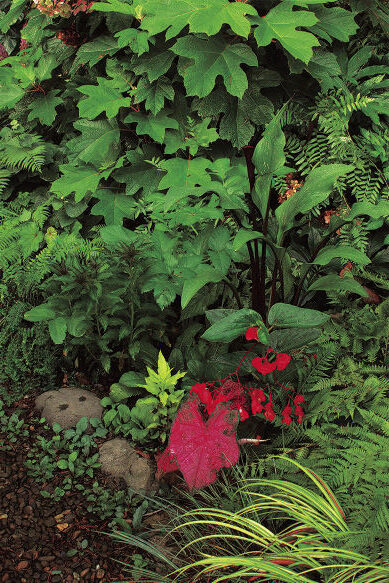

After dividing the potential garden space, you’ll be left with two beds: one primarily in sun and one primarily in shade. This is where the challenge arises—it’s easy to make a sun bed and a shade bed, but how do you make the area a cohesive whole? To solve this problem, Faye selected one side and planted all of it. Looking only for plants in one exposure category at a time was straightforward and simple. Faye chose to plant the full-shade section first because she had tons of shade plants waiting to find a new home after her move.

With one side of the bed planted, Faye tackled the other side. To make the two halves of the garden look like they belonged together, she needed to find “twins” for the opposite side. To do this, she selected a plant from the shade bed and identified one of its prominent features (its color, texture, or form); she then found a full-sun plant that also possessed that feature. ‘Annabelle’ smooth hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens ‘Annabelle’, Zones 4–9), for example, has fluffy white blooms in the shade, so Faye chose the similarly fluffy white flowers of spider flower (Cleome hassleriana cv., annual) to be the hydrangea’s full-sun twin. And the long fronds of the shade-loving crested lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina ‘Vernoniae Cristatum’, Zones 4–9) have a fine texture, similar to the needlelike foliage of the sun-loving Arkansas blue star (Amsonia hubrichtii, Zones 5–8).

Your garden’s unplanted side will eventually begin to fill up. Not every plant needs a twin, but finding matches for roughly half of your plants is something to strive for. Because each side of the garden will likely be a different size, you may find yourself with extra room. At this point, you can fill in the blank spaces with any plants you choose. The two sides of the bed will still look cohesive, and everyone will assume that it was a happy accident. It’s up to you whether you let them in on the real story.

Get a Unified Look Despite a Varied Exposure

It seems like an impossible feat: Create a bed that looks cohesive despite stretching from full sun to full shade. But this challenge is an unfortunate reality for many gardeners. How can there be flow in a garden that has plants that need 10 hours of bright light as well as those that will burn if they get only two hours of sun? To get the bed of your dreams, you’ll need to find exposure “twins.” These are plants that share a similar, striking trait (like a vibrant flower color) but that thrive in different exposures. The twins do not need to be mirror images of each other nor be planted directly next to one another. Here are a few examples of exposure twins found in Faye Beck’s garden. Their relationship is subtle, yet their presence gives the bed undeniable cohesion.

Connecting the sides

| Sun | Shade | |

|

Color |

A. ‘Victoria’ mealycup sage (Salvia farinacea ‘Victoria’, Zones 8–11)

|

B. Bigleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla cv., Zones 6–9)

|

|

Texture |

C. ‘Shasta’ doublefile viburnum (Viburnum plicatum f. tomentosum ‘Shasta’, Zones 4–8)

|

D. Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis, Zones 2–8)

|

|

Form |

E. ‘Jade Princess’ millet (Pennisetum glaucum ‘Jade Princess’, annual)

|

F. ‘Aureola’ Japanese forest grass (Hakonechloa macra ‘Aureola’, Zones 5–9)

|

How Light can Affect Color

If color is the attribute that you want to use to find a twin for the other exposure side of the bed, you need to be aware of a few things. Just as paint colors on the walls of your home can look different depending on the amount of sunlight streaming through the windows, colors in the garden can appear more or less saturated depending on how much light hits them. Here are a few things to keep in mind before selecting colorful plants:

Moving plants temporarily out of their comfort zone is a good idea

If you are selecting a sun-loving, red-leaved plant at the nursery, take it to a sunny spot and then to a shadier location to get an idea of what it will look like in late afternoon or evening light. You may be surprised to find that some plants look hot pink in low light, and that may affect your plant selection.

Certain colors can wash out or burn too brightly

The classic examples of washed-out colors are white (which can burn your retinas in the sun) and pink (which loses its brilliance in bright spots). Pale yellow is often a better choice for getting “the look” of white in the sun, and magenta washes out to pink in bright light.

Danielle Sherry is the senior editor, who has happily visited Faye Beck and her gardens several times—and, each time, sees something she has never seen before.

Photos: Danielle Sherry; Michelle Gervais. Illustration: Elara Tanguy

To identify many of the plants shown in this article, visit FineGardening.com/extras.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in