by Ruth Lively

February 1999

from issue #19

Call your county extension office. How many times have you heard or read that advice? For years it’s been the standard bromide in the gardening press when space is too short for a fuller explanation, or when answers depend on local conditions. What’s a county extension office? And how can it help?

The cooperative extension service has a presence in every state. The name’s a mouthful, but it makes sense. The organization is a cooperative effort between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, land grant universities, and local county governments. The cooperative extension service’s role is teaching residents about university research in the fields of agriculture, horticulture, youth, natural resources, food safety and nutrition, and what we used to call home economics (now “managed family resources”).

But when you do make that call to ask about what’s bugging your beans, or which tomato does best in your area, or when to expect the first fall frost, who answers your questions? Chances are it’s not a county or university employee, but a dedicated gardener—a trained volunteer called a Master Gardener.

The Master Gardener program was launched in Washington State in the early 1970s. Home gardening was booming, and cooperative extension programs everywhere were stretched to the limit. There simply weren’t enough extension horticulturists (also called extension agents) to answer all the questions. Dr. David Gibby, then an extension agent in the Seattle–Tacoma area, had been experimenting with reaching the public through mass media, but his attempts had only increased demand. “My problem,” he says, “was how to get information to a mountain of people on a very low budget.”

Then he came up with the idea of training interested gardeners in exchange for help in providing answers to the public. After a year of planning, the first Master Gardener class, 120 strong, was trained in 1973. In that first year, Master Gardeners helped an estimated 7,000 Washington gardeners with problems. The program was an immediate success, and quickly spread to other counties and states. A quarter of a century later, Washington’s 3,378 active Master Gardeners logged 147,700 hours in 1997 serving nearly 348,000 citizens. At a value of nearly $13.73 an hour (based on The Independent Sector’s suggested value for volunteer time), this service was worth more than $2 million to the state of Washington. “I knew it had the potential to become something really big, but I had no idea it would grow this much,” Gibby says.

Master Gardeners are now the front line of the cooperative extension service, with training offered in all 50 states (click here for links to state Master Gardener Web sites), the District of Columbia, and four Canadian provinces. The phone pressure on the extension service is amazing (75,000 calls were answered in 1996 by Master Gardeners in Texas alone). Typically, the telephone is the most effective way to answer questions, but sometimes a phone call doesn’t do it. Some people show up in person, plant or insect samples in hand. In some areas, Master Gardeners even make house calls to assess a problem.

Gardeners in training

Training varies from state to state and even from county to county, but usually ranges from 40 to 60 hours. A few programs offer as little as 30 hours of training, while New York State’s program is a whopping 120 hours. There are sessions on soils and plant nutrition, propagation, insects, diseases, fruits, vegetables, weeds, indoor plants, trees, shrubs and herbaceous ornamentals, landscape design and management, lawns, irrigation, and more. Every program wraps up with special training in dealing with the public.

Courses are taught by specialists, usually extension horticulturists or faculty educators. The training typically consists of lectures, often with some hands-on instruction for things like pruning. At the end, there’s an open-book exam, since the point is not how much you’ve memorized but how well you can access information. Some states also have a practical exam, identifying plants, insects, or diseases. Participants receive a certificate only after successfully completing the course and fulfilling the required volunteer hours.

Over its 26-year life, the program has seen plenty of changes. In the past, there was a stronger emphasis on pesticide use, mostly because extension agents had a primarily agricultural orientation. One midwestern volunteer, who gardens organically, said the only hard part of the program is having to sometimes dispense information about pesticide use. A university extension horticulturist I spoke with, who took the course in 1982, recalls, “With no disrespect to my instructors, the attitude then was ‘What’s the problem? What do we spray on it?’”

These days, the course teaches integrated pest management (IPM) methods, focusing on how to have healthy plants, rather than how to eliminate pests. Van Bobbitt, Washington state coordinator, credits the Master Gardener program with pushing the extension service to offer more non-chemical alternatives. Volunteers discuss a variety of control methods, and in fact, cannot give advice on pesticide use over the phone, although they can send out information sheets.

The training itself is supposed to be free, but most states charge a fee to recover the cost of the materials, which is usually a manual and numerous information sheets. Fees run $50 to $75, although some are much higher (Connecticut’s is $200). In Washington State, the program still costs the participants nothing.

Finding people who love to share

The strength of the Master Gardener concept lies in finding people with a love of gardening and a desire to share. Founding father David Gibby again: “Some of these folks already have a lot of knowledge; they may be experts on roses, or oleanders, or a particular kind of fruit who have access to libraries and information that extension agents don’t have. In such cases you can find specialists who then become resources to the extension employees, who must be generalists.”

There’s another side to the coin, however. “You’re dealing with volunteers, who may have their own agendas,” Gibby points out. Sometimes those agendas differ from the one of the person who’s on the public payroll. “Then you have to reach a compromise. You want people who are giving in their nature.”

There are always more applicants than there are spaces in the classroom, which works to the program’s advantage. Administrators everywhere have had to become more selective. Van Bobbitt says this is in no way elitist. “There was a time when the idea was, let’s see how many people we can get signed up for the program. But this only created another population for cooperative extension to look after. Now, the number one criterion is not gardening interest or knowledge, but previous volunteer experience, something that displays a volunteer ethic. We can train people in gardening, but we can’t instill that ethic in them.”

The fact remains, however, that most people get into the program to benefit themselves. Anne Wood, a chef in the Chicago area, started gardening because she wanted to grow her own herbs. Pretty soon she realized she wanted to know more, so she decided to become a Master Gardener. She likes to write, so although she’s long since fulfilled her obligation, she continues to edit her group’s newsletter.

Sylvia Gatzy signed on after moving to North Carolina from New England. She was already a good gardener, but she needed to learn how to garden in the Piedmont. Later she answered phones in the extension office. “I was scared at first.” she recalls. “But as time went on, I learned an awful lot from the people asking the questions. It’s a two-way street.”

In Texas, Manuel Santos became a Master Gardener to help him in his job. The unforeseen result was a career change for Santos (see below). What Santos has to say about the experience sums up what I heard again and again from all parts of the country. “You’re continuously learning. Besides the education enhancement, the affiliation with the university system is a big benefit.”

Beyond the call of duty

Many participants go beyond the requirements. “We have some who put in hundreds of extra hours,” says Doug Welsh, coordinator for Texas “What they get out of the program goes far beyond the gardening benefits to themselves. For them, giving meets a personal need.” That’s the kind of Master Gardener the extension service loves to find.

Training is almost always on weekdays, which at first may seem odd, but weekdays are when there’s the greatest need for help. People who are available to take the training on weekdays will presumably also be available to volunteer then. That makes it hard for people who work full time to enter the program. There are exceptions, however. Doug Welsh says, “We’ve actually had people who take their vacations to do the training and then again to do their service. That kind of commitment is amazing.”

The Master Gardener program was intended as a tool for getting information to the public. Nobody expected all the public service projects: gardening with kids, particularly those at risk of getting into trouble, gardening with the elderly, with prisoners, with the handicapped. All of these programs have tremendous value.

Still, David Gibby thinks the cooperative extension service hasn’t really used the Master Gardener program as fully as it could. He says a bit wistfully, “I’ve always thought public television could be married with the program to reach a lot more people.” PBS, are you listening?

Bigger and better in Texas

“San Antonio has the best Master Gardener program in the United States.” So Doug Welsh, state Master Gardener coordinator for Texas, told me. I wondered how objective his assessment was. Welsh had once been extension horticulturist for San Antonio, but something told me this wasn’t just Lone Star chauvinism.

Bexar (pronounced “bear”) County, which is home to San Antonio, started its Master Gardener program only 10 years ago. It has graduated over 1,000 people, and nearly half of them remain active. That’s impressive when you consider Texas requires 50 hours of volunteer service each year to stay active. San Antonio graduates not one, but three, classes a year. Two classes are offered to the general public, and a third to the employees of the San Antonio Water Systems (SAWS).

The connection between SAWS and the Master Gardeners started with the utility’s Water Saver Rebate program. Because of the dry climate, water use is a big issue, and SAWS, one of two water utilities in the city, has an extensive conservation program. Most of the water used during the growing season goes to maintaining landscapes. Residential customers who maintain xeriscape plantings can qualify for a rebate. SAWS can’t afford the manpower to review applications and inspect the 600 to 800 landscapes that qualify each year, so they contract this out to Master Gardeners. The utility pays a nominal fee ($20) to the Master Gardener program, and the volunteers who do the work log service hours. (By comparison, the city of Austin, which has a similar program but uses employees to do the inspections, spends about $100 per landscape.)

Once SAWS recognized that Master Gardeners were more inclined to be savvy about water use, the utility struck an agreement with the cooperative extension service to offer Master Gardener classes to SAWS landscaping crews. Soon other employees got interested. For the past few years, SAWS has arranged for training on-site. Two-hour classes are held weekly at lunchtime. Even though it takes half a year to get through the 60 hours of training, the class is always full. “People are begging for it,” says Dana Nichols of the SAWS conservation department. “We benefit by having employees who are better educated about water usage, so we’ll do it as long as there’s a demand.”

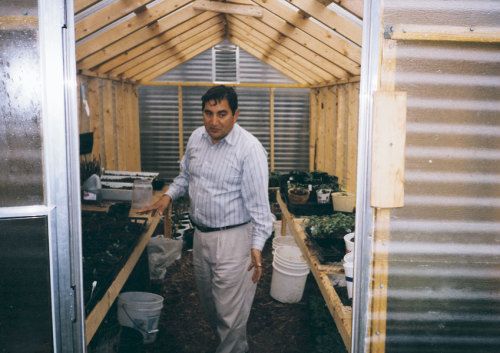

SAWS isn’t the only waterworks in town with a Master Gardener story. Manuel Santos, formerly a foreman with Bexar Metropolitan Water District, became a Master Gardener to fill a professional need. During his tenure at the water utility, Santos inherited oversight of the production department, which included grounds and landscaping workers. All of a sudden, Santos needed to learn about gardening. He did the Master Gardener training in 1989, the first year it was offered in Bexar County. For his volunteer service, he worked with juvenile offenders, landscaping parks. He obviously enjoyed the work, and was so effective that he was offered a job at the Bexar County Juvenile Probation Department.

He’s been there eight years. Meanwhile, his Master Gardener involvement hasn’t slackened.

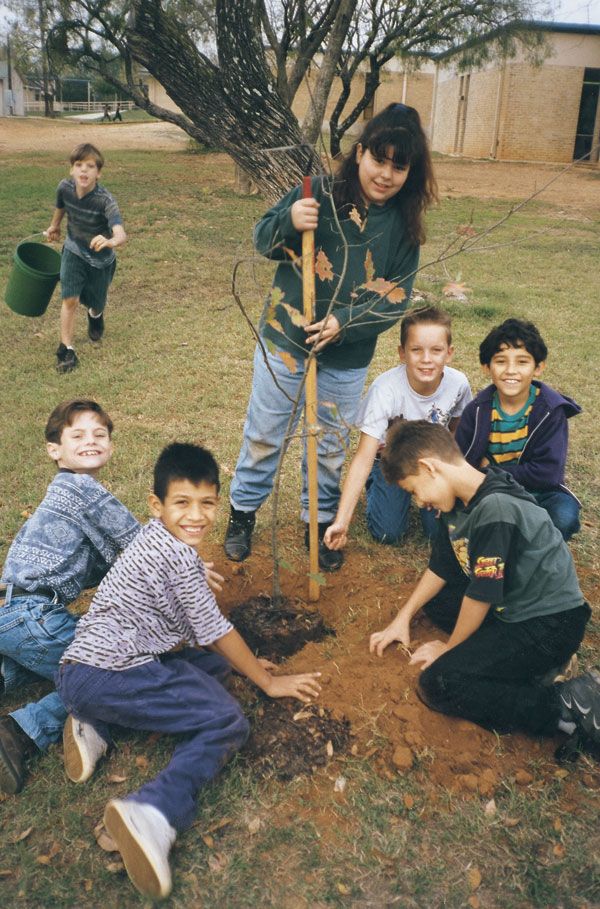

“There’s something here in San Antonio called in-school suspension, where student offenders do service like working on landscaping crews instead of being sent home,” Santos said recently. “The kids liked it so much they began to ask, ‘Why can’t we do this without being bad?’” One outgrowth of this is San Antonio’s Green Brigade program, in which the Bexar County Master Gardeners play a leading role. Kids show up on Saturdays to work on landscaping projects around the city. The program has received a major grant from the Department of the Interior, and numerous local and national awards for its work with youth at risk.

According to Calvin Finch, Bexar County’s extension horticulturist, there are more than a hundred projects in the county that the Master Gardeners run. Most projects have other partners—schools, neighborhood associations, nurseries, the parks department—but the Master Gardeners are the lead partner.

This year San Antonio will host its second international Master Gardener conference with members from the U.S. and Canada, and visitors from Mexico, which has a similar, though unrelated, program.

As for Doug Welsh’s statement, I’m inclined to believe it.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in