by Ken Haedrich

February 1998

from issue #13

Getting kids to eat vegetables is a conundrum. Battles over food can create stress in an otherwise peaceable household. And in an attempt to diminish the combat, parents may give in to a child who simply refuses to eat “what’s good for him.” I’ve looked at this quandary up close, and have spent the better part of my adult life cooking for my own four vegetarian kids, so I have some suggestions for parents cooking in a veggie-hostile environment.

First, know that all the tricks and good recipes in the world will do you little good unless you adopt the right attitude. Gauge your own attitude quotient by taking this quiz:

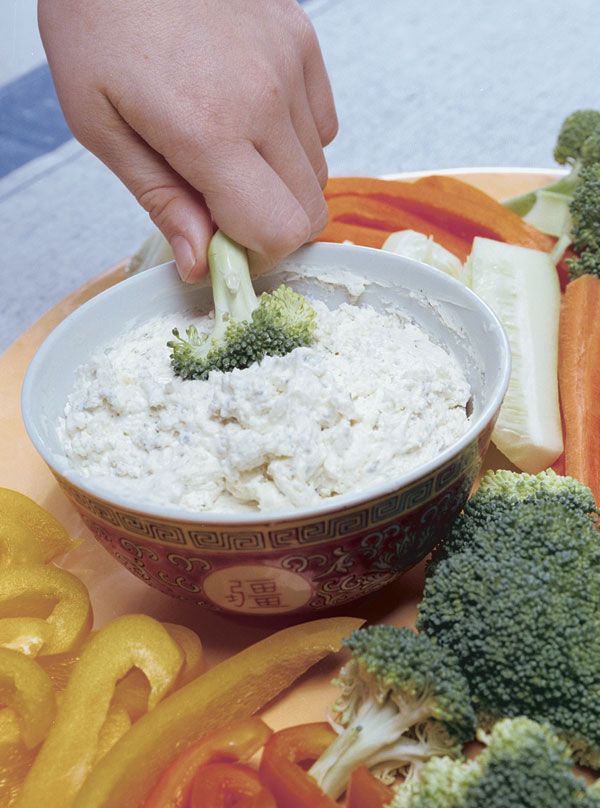

You, a veggie lover, have prepared a stunning meal featuring an array of fresh and toothsome veggies that would make Martha Stewart green with envy. Now, the fruits of your labor are spread sumptuously before your gathered clan: delicately steamed asparagus spears glistening in lemon juice and butter; fragrant, roasted new potatoes flecked with fresh rosemary; and a kaleidoscope of crudités with a savory dip. Then your eight-year-old lets fly that he would rather have a bowl of corn flakes. How do you respond?

a. I’ve spent half the day cooking and you want a bowl of

cereal?

b. You’re not leaving the table until you’ve eaten everything I’ve put on your plate.

c. I’ll give you a dime for every piece of asparagus you eat.

d. Great! There’s more for me.

Now, I do not claim that I’ve never said some stupid variation of answers a, b, and c. But experience has taught me that the only sensible attitude—essentially one of “no pressure”—is best expressed by answer d. Using guilt, threats, or bribes to get kids to eat anything undercuts the whole idea that we eat for pleasure. What it does is plant the erroneous and potentially dangerous idea that we eat to please someone else, to avoid sanctions, and otherwise manipulate—notions that can cause conflicts ranging from eating disorders to clever reprisals.

Dialogue is the best seasoning. Even if “no pressure” is the best policy, it isn’t enough to merely take a hands-off approach. You have to ask questions, experiment, and listen to feedback. When you do this, kids know their wishes have been heard, and they’re more likely to try something new. And so long as the comments are instructive and not cutting, there’s no better place to talk about food than at the dinner table.

The gospel of good food is a risky one to preach to kids, but there’s no doubt it’s important to convey. If we ate only for taste we’d eat Boston Cream pie all the time (or maybe apple pie if we’re vegans). In food, fat carries flavor, and sweetness is a preferred taste, hence our propensity to eat sweet, high-fat foods. But eating food with low nutritive value deprives us of those nutrients we need by displacing healthy foods. That leads to the age-old order to eat your vegetables—or you won’t get any dessert.

Let kids know about the importance of healthy eating, but don’t shove it down their throats. One day they’ll be the ones responsible for their own well-being, and they need the knowledge and skills to make good decisions about food.

Kids have a refined texture detector. Mushy and slimy are two important words in a kid’s vocabulary of texture. If a vegetable doesn’t make it past a child’s built-in texture detector, forget it. (And don’t even think about commingling foods with different textures; keep that corn away from the mashed potatoes, and both away from the greens.) Here are a couple of examples: Most of my kids like strips of raw bell pepper. But the same ones who’ll eat them raw will treat sautéed peppers with utter disdain. Or take sautéed mushrooms. Here’s a food none of my kids will eat because it’s too slimy. On the other hand, if I purée those sautéed mushrooms with broth to make mushroom soup, the kids are in heaven.

Legions of kids like raw veggies with dip. Cucumbers, broccoli, celery, carrots, and sweet peppers are some of the most popular choices. And of course, the right dip makes all the difference in the world.

Watch out for size faux pas. When you can wrap your fingers around your veggies, as you can with crudités, and nibble off what you like, size is not a concern. When it comes to cooked dishes, fork-and-spoon foods, physical size matters. And the younger the child, the more it matters.

Imagine you’re five years old and quite content with the bowl of vegetable soup your mom just placed in front of you. You slip in your spoon and fish out a piece of broccoli, not just any piece but a mega-floret. You move the spoon toward your mouth and quickly calculate that, even at maximum aperture, there’s no way this baby is going in whole. Such is often the fate of little kids living in the world of adult foods.

I make light of the situation, but I think the Too-Big-Veggie Syndrome is a stumbling block for kids, and when the veggies are cut too big, kids lose interest without bothering to say why. When they do, it’s simplest to conclude they don’t like broccoli. Whereas the truth is they’re just intimidated by the size. With cooked vegetables, I cut for the youngest person at the table. And if that’s not feasible, I do a separate portion for the littlest ones.

As I said earlier, I haven’t always been master of the calm retort when one of my kids posits that a certain veggie I’ve lovingly prepared looks like something the dog brought in. But if we listen carefully, we can do a lot to remove the obstacles between a child and a pile of vegetables. Here are a few tips that might serve you:

Cook with your kids. To kids, cooking is one of those mysterious adult things. Involving children in the process of cooking connects them with the food. Make sure they’re supervised, and start with cutting and mixing ingredients.

Basic is often best. I’ve seen one too many articles suggesting that if we dress up broccoli to look like reindeer, or Madonna, kids will eat it. Veggies don’t need to be cute to be good. A pat of butter, a squeeze of lemon juice, and a sprinkle of salt will serve you better.

Stay in season, when possible. It’s pretty darn hard to eat only what’s in season. But a lot of the “fresh” veggies we get at the supermarket can be pretty tasteless, and we can’t blame kids who find them underwhelming. In winter months, lean toward storage vegetables like roots and squashes and those that travel well like kale.

Serve lots of vegetables, and often. Kids are bound to eat when they’re hungry and bound to pick among a number of different vegetable dishes.

Grow a garden or visit a farmer’s market. This also gives kids another tangible connection to their food. Your own tomatoes or green beans always taste best.

Try roasting. Roasting concentrates sweetness and flavor and can be done successfully with most vegetables.

And if at first you don’t succeed, don’t lose hope. If a child doesn’t like something at age five, it’s not necessarily a chronic condition. My two older kids love tomatoes now; a few years ago they wouldn’t sit at the same table with a sliced tomato. Tastes change.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in