by George L. Egger II

April 1997

from issue #8

Heaping truck loads of a few standard vegetables aren’t my thing in gardening. Plenty of people out here in the great midwest farm belt fill that order. On my little one-third acre in central Illinois, I cultivate scores of different plants. I pursue the best strains, pick the fruit at its peak in meal-size batches, and work to keep a fresh supply coming all summer and as long into the fall as I can manage. I use homegrown seedlings extensively, replanting as soon as the crop in the ground is finished producing.

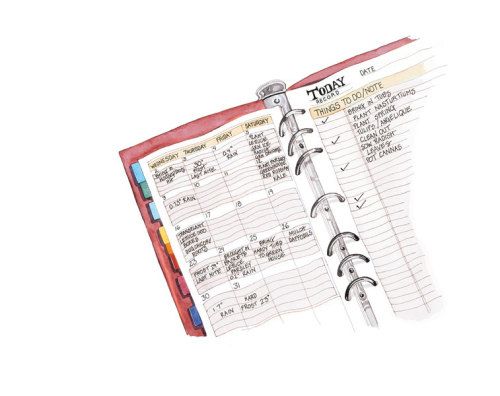

Remembering what to plant when and keeping the replacements coming is tough enough with familiar varieties. With all the new types that keep appearing every year it’s impossible. I could never hope to succeed without the generous assistance of my day planner. This tool is as essential as a spade, yet an animated, creative extension of the garden.

Consider yourself a garden executive

Over the years, I have tried many methods of collecting my garden information and ideas: journals, bound ledgers, notebooks, sketch pads, and calendars. Information was difficult to retrieve from all of them. Now I use a day planner. It is specifically designed for busy executives to track the zillions of things they must do. My day planner, which I modified to meet my gardening needs, does exactly that. It’s a single binder combining a calendar, daily sheets for journal entries, and an address book where I list varieties with a letter grade of their performance. I also have a separate tabbed section dedicated to each bed in my garden, with running lists of tasks to be completed for each one. I have several sketches of the bed at key stages. I experimented with drawing paper, sized and punched to fit my planner, but eventually got pockets to hold sketches. So it doesn’t take much by way of supplies to get started.

The garden journal’s details are your guide

Certain information is essential to make a journal useful, but the level of detail is up to you. I log the weather carefully: first and last frosts, dates and amounts of precipitation, and average night and day temperatures. I record soil preparation and amendments. And I also note the source of seeds and plants so I can weed out unreliable suppliers.

Beyond those basics, I record all manner of events and insights. Did that touted tomato type grow vigorously, withstand pests and disease? Did the new broccoli planting head before that early freeze? How long did it produce usable side shoots? Which beds are due this year for manure? When was each variety sown, transplanted, set out, and harvested? I make a special effort to record the elements of this last question on the relevant day in the calendar.

The calendar entry prevents information from getting lost. I can’t tell you how often I’ve read of the perfect time to plant, say, mâche, but then forgot when spring rolled into town. I now grab my planner, flip to the month of April, and write, “plant mâche!” on the 15th.

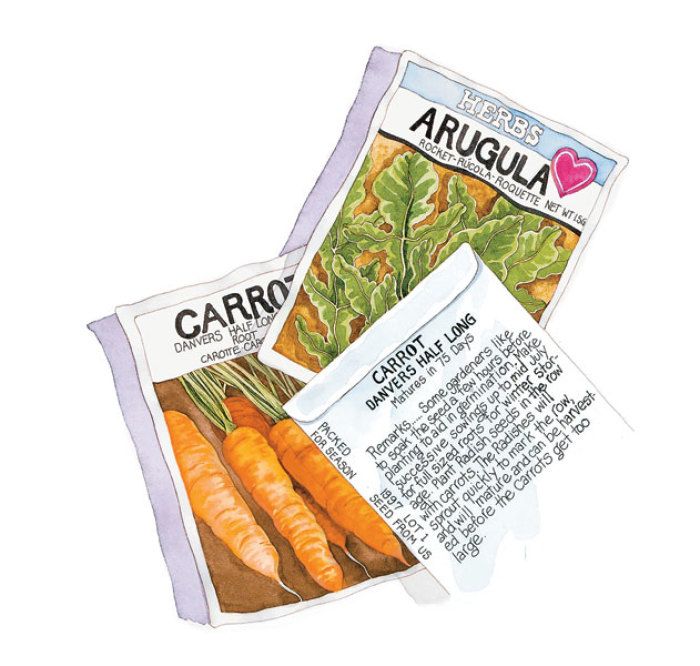

Find your garden’s unique patterns. Sure, the seed packet may say to start the plants six to eight weeks before transplanting. But that may not be precise enough for your garden. For example, the time range usually allows for hardening off plants, which will happen faster in midsummer than in early spring. If the timing is wrong, and you’re doing succession planting, it could mean a gap in supply at mid-season, or losing plants because there is no place in the garden to put them.

As you build your journal each year, your calendar will come closer and closer to a perfect planting guide for your exact microclimate. This is particularly important if you’re trying to figure out how to manage succession planting using a gardening book written for a different part of the country or even a different continent.

In years with abnormal weather, I can consult the more detailed notes I made in the planner pages devoted to individual beds and my entries on the sheets logging daily activities. Study of these details often suggests ways to at least partially offset the current conditions. For example, lettuce varieties that did well for fall planting are worth trying in an unusually cool summer. Melons that were choice in a very wet summer are good candidates for drip irrigation in a dry year.

Let the garden past lead to the spring ahead. Fall offers a good time to consider the successes of the garden that was and begin heading off potential failures in the one that will be. By the time of the annual deluge of garden catalogs, my journal provides a good shopping list and, more important, a day-by-day planting timetable for the coming year. The grade I put in the address book for each variety really saves time when perusing those catalogs.

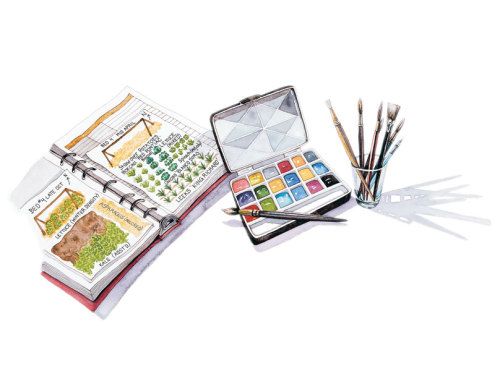

Simple artwork brings a journal to life

Botanical illustration, which has become so popular, was originally a way of collecting field notes with pen or pencil. Watercolor was a perfect way to tint such notes. How unfortunate a conceit that only artists should sketch. I am no artist. But I am an incurable sketcher of gardens, especially my own. I sketch each bed in my garden several times during the growing season to show the succession of plantings. Just a few lines represent each variety. A few brush strokes of watercolor over the pencil lines add life. If you haven’t tried this since your school days, don’t be inhibited. It’s easy.

Of course, documenting the garden with photography has its own rewards. The clarity and beauty of fine photography offers quite a thrill. But the equipment can be bulky and expensive, and processing film can become taxing. And cameras don’t record the names of plant varieties. So I prefer my sketch pad, which has the added advantage of ignoring power lines and pink flamingos.

Sketches capture a great deal of information. If you rotate crops, it will be easier the following year to orchestrate the movement when you have a few pages of sheet music. Using watercolors has taught me the decorative value of vegetables. I now lay out my beds with an eye to color and texture. Through sketching, I see a new world in my garden.

Colored pencils or pens are fine to record color, but I prefer the traditional watercolors in a pocket box for travel, and tubes for use at home. Lightweight watercolor paper, such as 90 lb., works well for me. Since sketching and note-scribbling are hard on a pencil point, I use a mechanical pencil with a 0.5mm lead.

Once you begin sketching, you might well find, as I did, that the effort becomes a starting point for more serious work. And once you begin writing down thoughts and ideas, you may find bits of verse appearing here and there. Just relax and have fun. A true gardener’s journal is as unique as the gardens and the gardeners, themselves.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in