A garden planting of ferns conjures up images of shaded retreats and cool walks by wooded streams. Yes, ferns do abound in the deepest, darkest woodlands. But not all ferns are limited to the shade. They grow in every conceivable place. I have found these seemingly fragile beauties growing in rock crevices, on sun-baked cliffs, among clumps of desert cacti and in the whirling mist of pounding waterfalls. Ferns are tougher and more varied than most gardeners realize, yet they epitomize simplicity and elegance. This combination of qualities makes them versatile garden plants. The majority of the ferns covered in this article range from USDA Hardiness Zone 4 (–30°F) to Zone 8 (10°F), and some will withstand the extremes of Zone 2 (–50°F) and Zone 10 (30°F).

Garden ferns fall into two broad groups based in their preferred habitat: ground-dwellers and rock-dwellers. Ground-dwellers adapt with ease to garden conditions and are popular plants. In the wild, they grow in open woodlands, swamps, marshes, and conifer forests; they are found on shaded banks, along streamsides, on dead logs, and on mossy hummocks.

Rock-dwellers exploit bare cliff faces, shaded overhangs, the sides of waterfalls, the tops of boulders, and even the trunks of trees. Most of them are best left to experienced growers, although a few are easily cultivated in a rock garden or on a stone wall. Because of the specialized treatment many rock-dwellers need, I will cover only ground-dwellers in this article. This group of ferns alone contains enough variety to fulfill the majority of garden needs.

Suggested Uses and Combinations

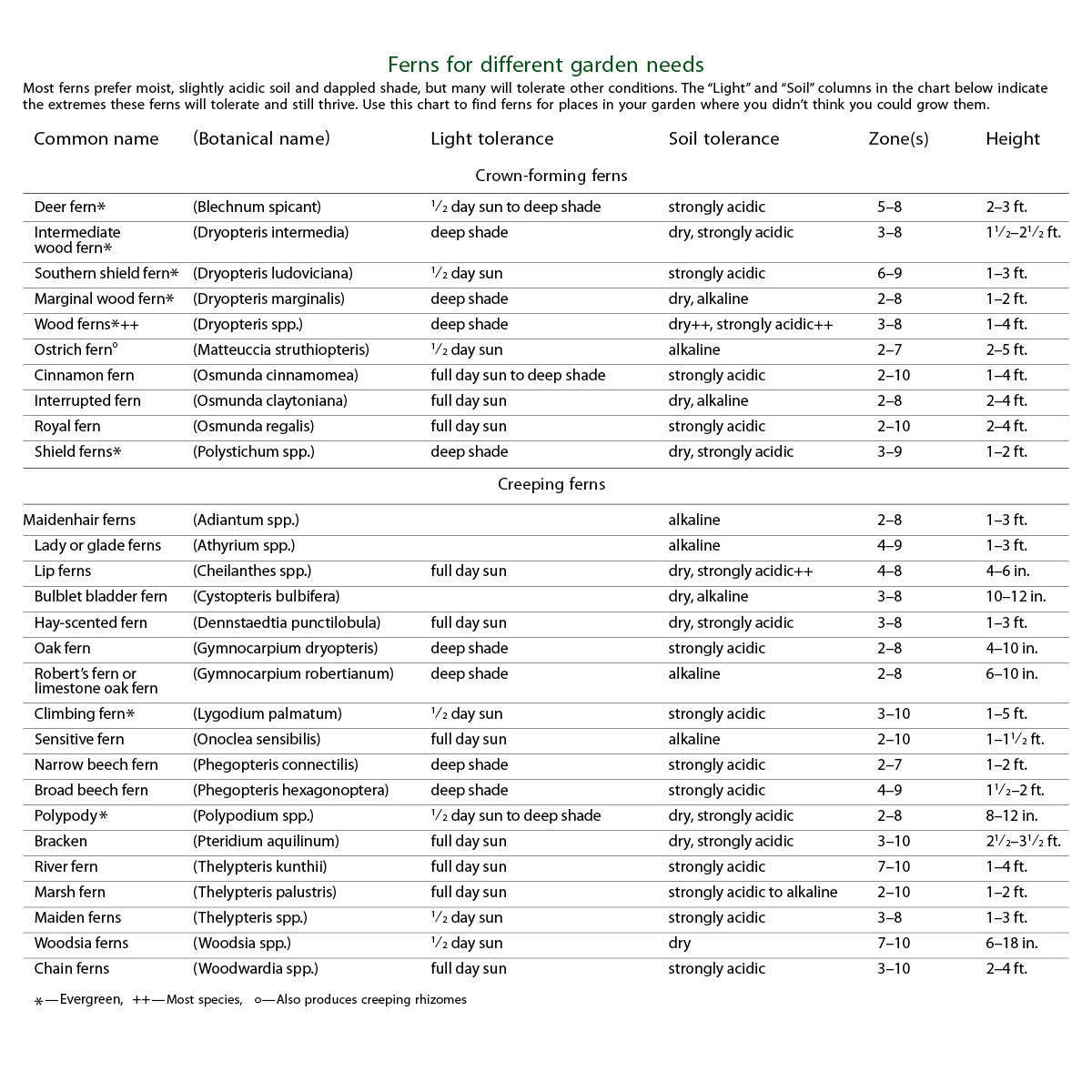

Since ferns are not limited to shade in their native habitats, we should not confine them to shaded retreats in our gardens. I use them in formal as well as informal settings. I plant them alone as accents or in combination with wildflowers, perennials, and flowering shrubs. The wide variation in foliage texture, cultural requirements, and size ensures a fern for every garden situation (see chart below).

Ferns have two basic growth forms: creeping and crown-forming. Creeping ferns grow from trailing rhizomes or stolons and spread through the garden easily. Their fronds are borne in loose clusters or in lines along the rhizome. Crown-forming ferns grow from upright rhizomes and carry their fronds in a circle or tight vaselike cluster.

Foliage is a fern’s major endowment, so consider the color and texture of the frond carefully when choosing these plants. Mixed plantings of ferns by themselves or with other foliage plants are very effective. The gray-green fronds of marginal wood ferns (Dryopteris marginalis) look great with blue hostas and purple coralbells (Heuchera ‘Palace Purple’). Chartreuse interrupted ferns (Osmunda claytoniana) combine well with dark evergreen ferns and variegated foliage. I love soft-green fronds juxtaposed with the stiff blades of ornamental grasses, or the shiny fronds of deer fern (Blechnum spicant) and many shield ferns (Polystichum spp.) glistening in filtered sunlight. In a planting that is predominantly ferns, mix textures and add evergreen ferns such as wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.) and Christmas ferns (Polystichum acrostichoides) for winter interest.

Large ferns form a perfect backdrop for herbaceous plantings; use them in a roomy border with large perennials such as rhubarb, plume poppy, hibiscus, and hosta. Insert them in foundation plantings along with or instead of traditional shrubs; large ferns are perfect for hiding the “naked ankles” of sparse shrubs or perennials. Plant them along fences or walls to break up a flat expanse. Mass plantings of ostrich ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris) and Osmunda species are very effective for filling bare spaces or adding depth in the shade of tall trees.

Moderately sized ferns such as New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina) and maidenhair (Adiantum pedatum) have many possibilities in the garden. Use them in combination with perennials, bulbs, and spring wildflowers. Their unfurling fronds are a beautiful complement to spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), blue phlox (Phlox divaricata), and others. And the fronds will fill in the blank spots left when wildflowers and spring bulbs go dormant.

Try ferns along a shaded walk to define the path or on a slope to hold the soil. Ferns with creeping rhizomes are best for this purpose. Some rhizomatous ferns are rampant growers. Plant these where they can spread to form lush ground covers and fill in under shrubs.

Crown-forming ferns make excellent accents alone or in small groupings because of their graceful vase shape. They are slow growing, so you needn’t fear they will take over the garden the way some running ferns will.

For low wet areas, chain ferns (Woodwardia spp.), Osmunda species, and marsh ferns (Thelypteris spp.) are stunning. Combine them with the spiky foliage of water irises, ligularias, and arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.).

Cultivation of Ferns

To be a successful fern gardener, you must match the plants with the conditions in your garden. Group ferns by their growth requirements when using them with flowering plants or when combining several species. Carefully arrange them by size within a mixed planting. Fronds are a fern’s best attribute, so don’t hide them in a mass of inferior foliage or plant them too thickly.

Most ferns spread quickly, and some grow quite large. Know their habits, sizes, and spreads before planting. The larger ones resent disturbance once they are established, and moving them may sacrifice their vigor for years.

Ferns generally require rich, moist soil with extra organic matter, but some prefer drier, less fertile soil. Although most ferns grow in neutral to moderately acidic soil, some are very fussy about pH. Research your plants’ needs, and have your soil tested by your county cooperative extension service to determine soil type, fertility, and pH.

Prepare the soil bed by double digging or at least by turning to a spade’s depth. Incorporate an ample supply of compost and manure to improve the friability of the soil. Add a light sprinkling of organic fertilizer if the need is indicated by a soil test.

Buying and Planting Hardy Ferns

Garden centers are finally catching on to the rising popularity of ferns, although they still offer a limited selection—mostly standard native species. To acquire any but the most common species, you will have to order through the mail.

Large plants at low prices usually mean you are purchasing wild-collected plants. Bonus plants sharing the pot with the fern are another clue. These ferns may come from parks and preserves and may have been removed illegally. Don’t be afraid to ask the vendor for his or her sources if you wish to help put a stop to this practice.

It is best to plant in fall or early spring. Ferns from a garden center will be potted, but mail-order plants are likely to arrive bare-root. Remove potted plants from their containers. Very carefully score the root ball with a sharp knife, or gently tease the root ball apart with your fingers. This breaks up the solid mass of fibrous roots that often forms along the container wall, and it loosens the potting soil.

Many commercial potting mixes are lighter than garden soil and can dry out faster. This is detrimental to the fern until it establishes a new root system in your garden soil. Remove the mix from the root ball to avoid problems. Plant the fern at the same level at which it was growing in the pot. For bare-root plants with creeping rhizomes, this should be ½ to 1 inch below the surface. Large rhizomes can be planted deeper. Planting too deeply, especially for plants with single crowns, means certain death. Osmunda species, Dryopteris species, and ostrich ferns are particularly fussy about this. Place their crowns 3 to 5 inches above the soil, depending on the size of the plant. If plants are dry, soak their root systems in water for an hour before you plant them. If they are small, pot them up for a few months until they are better established.

Fern Maintenance

Ferns are truly low-maintenance plants. Few weeds compete against ferns grown in shade. In sunny gardens, dense fronds shade the ground and discourage weeds. A light mulch of shredded leaves or bark helps eliminate weeds that persist and conserves moisture. Ferns never need staking, pinching, or pruning, except for removal of an occasional damaged frond. Pests are few; slugs may be a problem, and scale may appear on a stipe or rachis, but you can control them with approved organic pesticides. Remember, the fruit dots on the back of the fronds are not insects; these are the fern’s way of propagating itself.

In the North, consider a winter mulch of leaves or straw to protect the crowns of dormant plants. Apply the mulch after the ground freezes when you can be sure the plants are dormant. Each spring, remove last fall’s mulch from the fern bed, shred it, and return it to the bed. Do this very early in the season to avoid damage to emerging fiddleheads (young unfurling fronds). Raking is not advised because it may damage crowns and growing tips.

Fertilizer is seldom needed as long as mulch is left to decompose. A topdressing of well-composted manure added every two years helps build the soil and adds nitrogen.

With this minimal attention, your ferns should thrive for many years. You’ll be as enamored of them as I have been since I was transfixed by a clump of wild maidenhairs as a boy and wrote, “They lifted their delicate fronds, like lace horseshoes, a foot above the ground litter.” For me, the enchantment of ferns will never wane.

—C. Colston Burrell is a garden designer, writer, photographer, and lifelong fern enthusiast. He gardens in Minneapolis.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in