Amid all the lush tropicality of the plants we grow in the Southeast, sometimes I crave something a bit more conservative. Think Scandinavian: efficient, solidly built, and designed to stand strong through the spare times of winter—in other words, something coniferous. Dwarf conifers may be unadorned with flowers, but they have gorgeous profiles, elegant textures, steadfast shades of green and blue, and even touches of gold.

There’s no substitute for a dwarf conifer when that is what your gardening heart desires. However, many a southern heart has been broken by the traditional dwarf selections of spruces (Picea spp. and cvs., Zones 2–8), firs (Abies spp. and cvs., Zones 3–8), and yews (Taxus spp. and cvs., Zones 5–8). Zone 8 in Portland, Oregon, is not the same as Zone 8 in Portland, Alabama, come July. Northern species of conifers melt faster here than Frosty on a sunny day. But all is not lost. The conifer division is a large one, and heat-adapted species are out there; you just have to know what to look for.

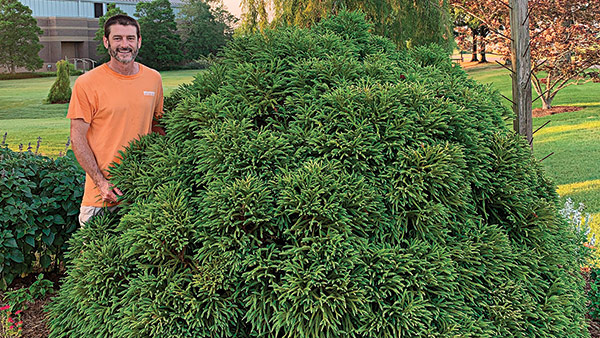

I’m fortunate to know better gardeners than myself, so I turned to Mary Griggs, a Charlotte-area plant enthusiast extraordinaire, for her experience-based recommendations. Knowing her passion for plants, I challenged her to pick her top three dwarf conifers for the Southeast.

‘Split Rock’ hinoki cypress (Chaemacyparis obtusa ‘Split Rock’, Zones 4–8b)

Mary says, “The reason I Iove it is the color—such a gorgeous blue cast, and it holds too. This plant is just plain pretty.” I’d add that it’s a great size, growing about 6 feet tall by 6 feet wide, and it doesn’t grow painfully slowly to get there.

‘Tiny Kurls’ Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus ‘Tiny Kurls’, Zones 3–8b)

Mary says, “It’s native! But with twisty interest. And the size is just right again, maybe 4 to 6 feet tall by 4 feet wide. And even if it ends up on the tall end, it’s so easy to control the height of dwarf pines. You just remove the candles in spring and you’re done.”

Whipcord Western cedar (Thuja plicata ‘Whipcord’, Zones 5–8)

Mary says, “It’s just so different! What else looks like this? That texture! And I actually prefer it in pots over in the ground.” This cedar will grow 4 to 5 feet tall and 4 to 5 feet wide.

Knowing that Western cedars don’t appreciate summer heat, I pressed Mary on her choice of the whipcord Western cedar in particular and dwarf conifers in general. Her response: “I think the most important thing is drainage. If you can’t plant on a slope; you’ve got to plant high. And when you plant high, you’ve got to water it. For the first two years, put a bag or a soaker hose on it. After that, you’re good.” As I walked her garden, I noticed that while her conifers were sited for good morning and midday sun, they weren’t necessarily in full sun. I believe that’s an advantage for most dwarf conifers in our summers—excluding ground-cover junipers (Juniperus spp. and cvs., Zones 2–9).

If dwarf conifers are on your wish list, it’s important to get specific. Find the names of cultivars that are thriving in regional public or private gardens, and seek those out. It’s always a good idea to buy from Southern nurseries that grow their own plants. A nursery won’t continue to grow plants that don’t hack it.

Mary summed it up, “You do a little research, and then you listen to the plants.” Sounds like an invitation to try new things to me.

—Paula Gross is the former assistant director of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte Botanical Gardens.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in