by Cynthia Hizer

December 1996

from issue #6

Where did I put the arugula two years ago? And last year, seems like the tomatoes were in the main garden. Or were they by the rabbit hutch? Guess I can’t plant potatoes there this year. I think.

If you’re not keeping track of these details, you may not be getting the most out of your garden, or giving your vegetables all they need. And you may be making needless work for yourself.

Moving plants around from year to year is one of the best organic techniques to minimize disease and bug problems and to maximize soil fertility. Various rotation plans are popular. The simplest is “don’t plant the same thing in the same place two years in a row.” This strategy is designed to ward off pests. If the cabbage looper pupa nestles down in the cabbage debris in October and reawakens the following spring to more cabbage, that’s instant sustenance. But if you’ve moved the cabbage, the looper may die trying to find its food.

Some gardeners move plants around by family—nightshade, composite, mustard, allium, solanum, cucurbit. For this system, it’s helpful to have a working knowledge of Latin, as well as an intimate knowledge of plant parts. One well-known gardening expert suggests a ten-year rotation. But I get dizzy just thinking of the complications. What if I sell the house before ten years are up? Should the rotation plan be in my will?

I use a system that’s easy to implement and easy to remember without a notebook. I separate my crops based on their nutritional requirements. It so happens that the plants fall pretty neatly into leafy crops, fruiting crops, and root crops. A fourth division is for legumes— peas and beans—which technically are fruits, but get their own plot because they actually add more nutrients to the soil than they take. By default, this system separates families, and so helps diminish pest problems.

Leaf, fruit, root, legume. That’s my crop rotation plan. No detailed plant anatomy, no bookkeeping, and no Latin, which I still plan to learn some day.

|

|

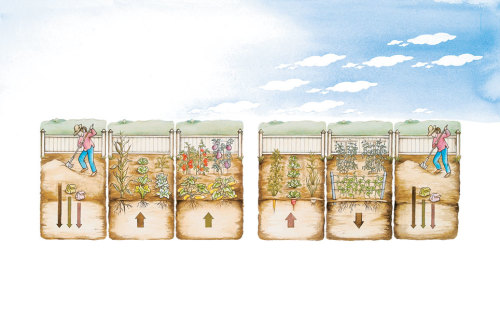

| If you rotate crops according to their nutritional requirements, then you can add soil amendments in rotation, too. This illustration, showing the same bed at six points (fall of prior year, year 1, year 2, year 3, year 4, and fall of fourth year), indicates how different types of crops take up different nutrients. See the chart below for specifics. |

| Fall of prior year | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Fall of fourth year |

| Leaf crop | Fruit crop | Root crop | Legume crop | ||

| Before planting anything, the author adds nitrogen in the form of compost and manure, along with phosphorus and potassium. | Lettuce, spinach, herbs, cabbage, broccoli | Tomatoes, squash, cucumbers, peppers | Onions, garlic, turnips, carrots, radishes | Beans, peas | The cycle starts anew, with the addition of nitrogen (compost and manure), phosphorus and potassium. |

| Leaves love nitrogen. | For fruits, it’s phosphorus. | Roots rely mainly on potassium. | Legumes put nitrogen back into the soil. |

Test the soil, and amend

I started by having my soil tested at a lab. Then I added the recommended amounts of nutrients—manure, compost, black rock phosphate, greensand, gypsum, and lime—to my entire garden. I did this in the fall so the amendments would have time to break down and become available to the plants.

In the spring, I divided the garden into four sections and planted each with one of the following groups: leaf, fruit, root, legume. Every year now, I rotate the plantings so the leaf group moves to where the legumes grew the season before, and the other groups all move over a section (see drawing at left).

Having four areas of roughly equal size makes this system work, even though you’ll probably want to grow more of one kind of crop than another. I made each division big enough to hold the largest group I grow, and I fill the empty spaces in my smaller rotations with cover crops.

If the areas aren’t the same size, when it comes time to put the largest group—say, the fruits—into a too-small space, you’ll be tempted to sneak some extra tomatoes or peppers in where they don’t belong. And then your nice, neat system has been breached.

Leaves love nitrogen. Plants like lettuce, spinach, herbs, cabbage, and broccoli need plenty of nitrogen to build strong stems and leaves. Nitrogen is the most readily soluble of all the nutrients, and therefore the hardest for the soil to hold onto. So it’s important to grow leaf crops in soil that’s had a fresh infusion of nitrogen. Manure or green manure (see the cover crop discussion at right) is the cornerstone. During the growing season, I also side-dress my plants in the leaf bed with alfalfa or fish or blood meal, and if necessary I spray them with a fish emulsion solution.

For fruits, it’s phosphorus. Tomatoes, squash, cucumbers, peppers—everything that develops as a result of a flower being pollinated—are fruits. These crops need generous phosphorus to set blossoms and develop fruit. If the soil is very rich in nitrogen, however, the leaves will be luxurious, but flowers and fruits will be few. Bone meal and rock phosphate are the best sources of phosphorus. Bone meal breaks down sooner, and needs to be renewed more often. Rock phosphate is my favorite; it takes a year to become fully available, but one application lasts five years.

Roots rely mainly on potassium. Onions, garlic, turnips, carrots, radishes, and other root crops are heavy potassium users. At the same time, they need even less nitrogen than fruits. That’s fine, because by the third year, most of the nitrogen has been used up, but the leisurely potassium is ready and waiting to go to work. My favorite potassium source is greensand because it also yields dozens of trace minerals and helps break up clay soil. Wood ashes, gypsum, kelp, and granite dust are also good potassium sources.

Legumes put nitrogen back into the soil. Beans and peas pull nitrogen from the air and store it on their roots. I grow these in the last year of the cycle because when their roots decompose in the soil, the nitrogen becomes available for next year’s leaf rotation. And the spent plants, when turned into the garden, add organic matter.

Amendments rotate, too

Another big benefit to this rotation system is that it’s easy to remember when and where to add soil amendments. Every fall, I amend only the bed that will hold next year’s leaf rotation. First I get my soil tested, and then I add manure and whatever amendments the test results recommend—lime, rock phosphate, greensand. At this time, I also spread compost over the entire garden. This program is based on using organic amendments, which stay in the soil longer than non-organic fertilizers.

If you’re not cover-cropping, you’ll need to add manure to every bed every year. If you don’t have a ready source of manure, well, plant cover crops.

Every rule has exceptions

I’ve had a hard time deciding where to put corn, potatoes, and garlic, but I’m happy with what I’m doing now. Corn is a heavy user of nitrogen so I grow it in the leaf rotation, even though corn’s a fruiting crop. In fact, I plant corn seed right into my lettuce patch; the growing corn shades the lettuce and takes over when the lettuce is finished.

Potatoes are roots, but they are also in the nightshade family, same as tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants. I noticed that the potatoes suffered more pest problems when they followed their relatives. Now I plant potatoes in the legume bed, which keeps them two years away from their kin.

And, finally, garlic is a little awkward because its growing season stretches from fall to summer. I now plant garlic in October in the fruit bed, which will be the root bed the following year.

Cover crops are part of the program

As a certified organic market gardener, I’m required to use cover crops. They’re so beneficial I urge you, too, to give them a try.

Cover crops are plants grown to enhance production, reduce weeds, and stimulate soil activity. When turned under, they compost right in the soil, which is why they’re also called green manure. I use cover crops during the off-season when I’m not growing vegetables, and also to fill blank spaces in those smaller rotations I talk about in the article.

I try to match the cover crop to my rotation plan. I sow legumes—clover, vetch, or alfalfa—in the legume bed and also in the leaf bed, which benefits from the extra nitrogen. After the leaf crops are harvested, I sow wheat, which discourages diseases and nematodes that might plague next year’s tomatoes and peppers. I mow the wheat when it’s about 8 in. tall, leave it on the bed over winter, and turn it under in spring.

After the fruiting crops are finished, I broadcast rye over the empty bed. Rye grows more mileage of roots than any other cover crop. The decaying rye roots leave the ground fluffy, perfect for growing shapely carrots and beets. In the hiatus between spring and fall root crops, I plant buckwheat, a grain that thrives in summer heat. Buckwheat discourages weeds and also loosens the soil. I’m careful to mow buckwheat before it flowers, or else it will become a weed. After the fall roots are harvested, I’m back to legumes.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in