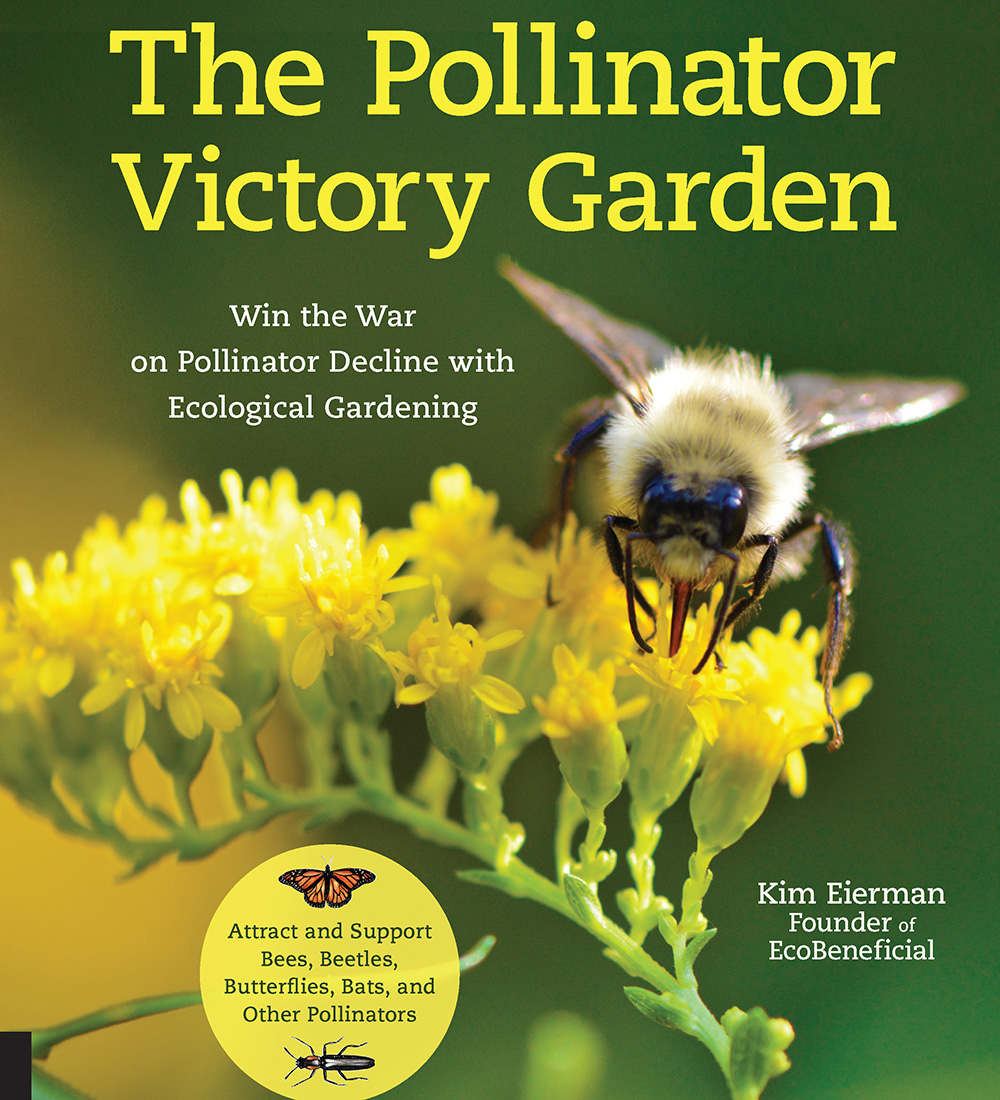

Recently I spoke with Kim Eierman of EcoBeneficial, an ecological consulting company based in Bronxville, New York, who is the author of The Pollinator Victory Garden: Win the War on Pollinator Decline with Ecological Gardening. We spoke about native pollinators, specifically bees, and what Mid-Atlantic gardeners should do to attract them and keep them around.

Background on native bees

Scientists estimate that about 4,000 species of bees are native to North America, out of 20,000 known species worldwide. Unlike the nonnative honeybee with which gardeners are so familiar, 90% of native bees are solitary. This means they live completely by themselves, except for mating. The rest of native bee species live in small societies, but in a much more limited way than honeybees. Bumblebees, for example, nest together in groups of 50 to 200 compared to a hive of as many as 50,000 honeybees.

Providing habitat in the ground

Kim believes that being aware of the behavior of our pollinators is important, not just to provide them with food resources but also to provide them with the proper habitat. Most native bees are ground nesters (about 70%), so gardeners should provide some areas in full sun with bare soil that are either devoid of plants or lightly vegetated. This could mean losing mulch in some areas of the garden. If there are ground-nesting bees in your garden, Kim suggests encouraging them. It’s hard to create an area to entice bees, as they will go where they want to go, but it is helpful to emulate a ground-nesting area for bees in your landscape. It does not need to be in a highly visible area.

Providing habitat in plant materials

The other 30% of native bees that don’t nest in the ground are considered cavity nesters. These bees prefer housing in hollow or pithy plant stems or holes in wood such as dead trees and logs. Kim urges gardeners to leave plants up throughout the winter or to cut them back and leave them in the garden so pollinators can use them to nest. Also, try to leave dead logs and trees in place. If a tree needs to be removed due to safety reasons, she recommends measuring where the tree will need to be cut to prevent damage to structures around it and leaving the rest. Bees will also create nests in beetle galleries and old mouse holes. She is aware that many gardeners will put a permethrin-soaked cotton ball in old mouse holes to prevent deer ticks, but she urges gardeners not to do that if they want to attract native bees to the garden, as the pesticide will also kill the beneficial invertebrates.

Bee hotels may attract other visitors

Kim says that man-made bee hotels are not great if attracting native bees is the goal. She cites a three-year study out of Toronto in which observers found that most of the residents in these hotels were parasitic wasps. Parasitic wasps are very beneficial as natural predators to pests, but in order to attract native bees, it is best to create a hospitable natural environment in the garden or yard.

Providing diverse food sources

If a gardener wants to increase native pollinator populations, then adding native plants is a good way to do that. Kim says that there are certain physical aspects of bee anatomy that limit what flowers they can forage to source nectar and pollen. One of these factors is tongue length. Short-tongued bees can successfully access only very open flowers, but long-tongued bees are able to get into long tubular flowers, such as tall larkspur (Delphinium exaltatum, Zones 5-8) and great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica, Zones 4–9). Another physical aspect is body strength. Only bumblebees can really force their way into a flower such as those on closed bottle gentian (Gentiana andrewsii, Zones 3–7). Finally, some of the earliest native bees, such as bumblebees, can tolerate a little bit of rain and cooler weather to reach the early spring–blooming plants.

Keeping native bees around

Once native bees are in the garden, Kim says it is very important for gardeners to plant a continuous succession of blooms beginning in early spring through late fall to keep them there. Examples of early blooming plants are red maple (Acer rubrum, Zones 3–9) and pussy willow (Salix discolor, Zones 4–8). Woodland-style gardens can play a huge part in attracting pollinators. Spring ephemerals such as Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria, Zones 3–7), squirrel corn (Dicentra canadensis, Zones 3–7), and spring beauty (Claytonia virginica, Zones 3–9) are extremely important for our native bees due to their early flowering period. These plants take advantage of the gentle sun and moist conditions, as they are some of the first plants to flower. They feed the pollinators and then die back by summer.

Garden layers mimic nature

Another tip Kim talks about is creating layers in the garden to try to mimic nature as much as possible. Try to design some part of your garden with a tree layer, an understory layer, and an herbaceous layer. She insists that a landscape with just trees and a lawn is not a hospitable environment for native bees.

Anyone with any size property can help to attract native bees. Kim acknowledges that landscapes in the suburbs can be disconnected to one another, but she says that having a pollinator-friendly garden is possible—and you can get neighbors on board as well. She recommends using signage in the garden to raise awareness about the possibility of having a suburban pollinator garden. Wherever you are in the Mid-Atlantic, it is possible to create a habitat for native bees and other important pollinators.

All photos from this article are courtesy of The Pollinator Victory Garden: Win the War on Pollinator Decline with Ecological Gardening by Kim Eierman, Quarry Books, 2020.

—Michele Christiano has worked in public gardens for most of her career. She lives in southern Pennsylvania and currently works as an estate gardener maintaining a private Piet Oudolf garden.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in