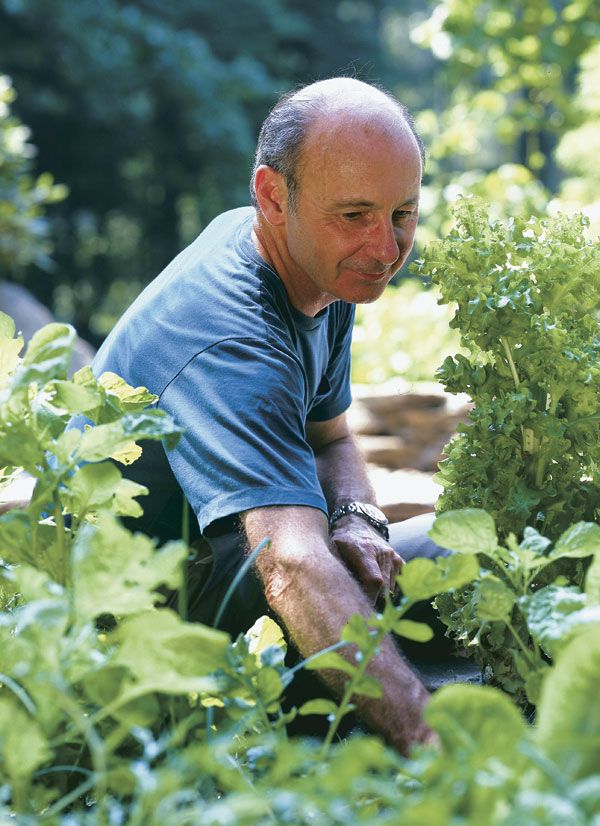

My wife, Jean, and I are devoted to the pleasures of the table, and our travels to southern France and Italy introduced us to the joys of Mediterranean food. Usually our hosts, wishing us to get the most from our visit, recommend the standard attractions: an ancient church, a museum, or a château. We tactfully agree that of course we must see these things, but ask to see the local market first.

Here, townspeople, vendors, and farm families come together, as they have for centuries, for lively conversation and the buying and selling of the ingredients for that most important of Mediterranean rituals—family meals. Herbs, olives, cheeses, and breads mingle their aromas with impeccably fresh fruits and vegetables of every color imaginable.

After these trips, we would return home to supermarkets filled with travel-weary produce, poor in flavor and questionable in the nutrition that is so important to us. We have long believed that a diet based on nutritious fruits and vegetables is the foundation of good health. We decided the only way we could have the kind of produce that suited us would be to grow it ourselves, cultivating a wide range of herbs and vegetables with methods that would enhance their flavor and nutrition.

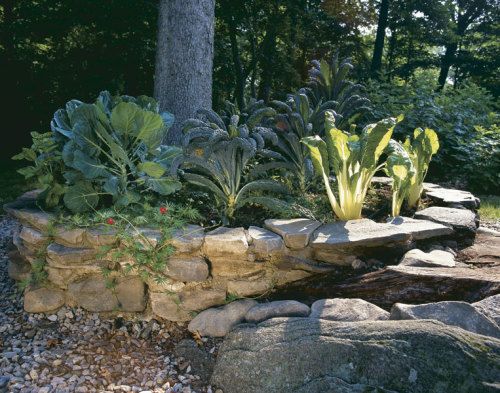

Stonework melds garden to landscape

Establishing our garden was not as simple as marking off a plot and turning the soil. We wanted the garden near the kitchen for the convenience of stepping outside and picking fresh as we cooked, and we wanted it to fit in aesthetically with the rest of the landscape. Because of the trees surrounding our property, sunlight is limited. A small area off the kitchen gets the most sun, and the plantings there were so overgrown the site needed complete renovation anyway. When we cleared the site, we discovered a rock ledge running under it, with bare rock showing in places. Getting enough soil depth would require raised beds.

I fit the beds into the landscape by building their walls out of fieldstone, which matches the stone fences so prevalent in our area. The location and shape of the beds was determined by the sloping terrain, by the rock outcroppings and plants we did not want removed, and by a bit of fancy. I kept the beds level by building the downslope ends of the walls higher, and buttressing them with larger stones. In this way the beds not only increased the soil depth, they also terraced the sloping ground. I laid the stones with mortar, which prevents soil from escaping and makes the walls more solid.

Building stone walls takes on a life of its own as one becomes immersed in the Zen of rock laying. Each stone is irregular and unique. Each space in the wall requires the right stone. And you have to be concerned with how each stone relates to the stones that are to come. You select a stone from the array spread out on the ground. If that one doesn’t work, you try another until you’re satisfied with the fit, then go on to the next space. The cares of the day vanish as you become engrossed in the fit of the stones.

We incorporated a nice rock outcropping into the central bed, which functions as an insectary, providing the food, water, and shelter that attract a beneficial insect population. Four beds, planted with edibles, surround it. Between the beds I spread native crushed rock—clean, low maintenance, and attractive. I filled the beds with my own soil blend of peat moss, sand, vermiculite, and compost.

Following nature’s lead

Following the example of nature, I control insect pests in the garden by developing the natural resistance of the plants and by creating a balance of nature. Plants in the natural world grow in decomposed plant residue that provides them with the full and balanced complement of minerals and organic compounds they need for healthy growth and for resisting insects and disease. These same minerals and organic compounds are essential for human nutrition and, as studies are beginning to show, for our own disease resistance, as well. They also give vegetables their rich, complex flavor.

Unless they are stressed, plants are protected by natural resistance and by predators that keep pest populations under control. I provide my plants with these natural compounds by feeding them a carefully formulated compost. I make my compost pile by layering leaves, grass clippings, kitchen scraps, weeds, and seaweed I gather from the beach. I keep the temperature of the pile below 100˚F so the nutrients won’t be degraded by higher temperatures.

The best beneficial predators are birds, particularly wrens. The birdhouses I put up near the garden quickly became occupied. I had planned to purchase a variety of beneficial insects by mail, but I knew that if I didn’t provide them with the necessities of food, water, and shelter, they would just leave. Beneficial insects often must endure periods when their prey is not available. During this time they need nectar to survive. So, in various places around the property, I plant flowers whose nectar the beneficials like. These include dill, white lace flower, sweet alyssum, cosmos, and yarrow.

I designed my insectary to draw the beneficial insects into the garden. So I planted it with some of these same flowers, including yarrow, whose dense growth habit furnishes shelter. I provide water by burying a ceramic basin up to its rim and putting a hill of gravel in it to give the insects access.

Like most people, I had not spent much time studying bugs. But my interest in natural control of insect pests required identifying the visitors to the garden as friends or foes. I found that with a good guidebook this is not really difficult, and is actually quite fascinating. It’s satisfying knowing who the insects are in the garden, and why they are there. Many of the insects were beneficials, and as time went on, more arrived. The dwindling number of pests indicated that the natural controls were succeeding. I now noticed that the flowers I had used to combine aesthetics with lawn care were actually supporting my beneficial insect population.

Four-legged nuisances are not a serious problem, apparently because of the location and construction of the garden. These creatures are a real nuisance in the neighbors’ gardens, and they certainly frequent our yard. However, except for squirrels, they don’t come into the garden. I attribute this to a number of things. Closeness to the house seems to be a major deterrent. Rabbits seem intimidated by the raised beds. Deer supposedly do not like walking on crushed rock. Squirrels sometimes gnaw the tomatoes, perhaps seeking moisture in the dry part of the summer. But after I put water in the insectary, they’ve been less of a problem.

Abundance from limited space

I grow salad greens in a bed that receives only partial sun, and I find they do better if partially shaded. I grow other vegetables intensively in the three beds that get full sun for about six hours a day. It’s less than ideal, yet sufficient even for sun-loving eggplants. As a precaution against insect infestation, I divide these vegetables into three family groups—tomato, cabbage, and bean and squash—and rotate each group to a different bed each year.

I get maximum productivity from limited space by growing most of the plants vertically. But I let melons and cucumbers overflow the beds and sprawl onto the crushed rock. It keeps the fruits clean, and avoids the problems that come from fruits lying on soil.

We are especially fond of tomatoes, sweet peppers, and eggplants, and there are so many varieties that tempt us. Since there just isn’t enough space in the beds, I end up growing some in pots, which I treat as small, movable, raised beds.

The beds are planted with flowers, which not only add color and fragrance, but are also edible and help control pests. For instance, nasturtiums trap plants for aphids, and signet marigolds release a lovely scent that apparently interferes with the ability of pests to home in on their target plants.

Simple rewards

The rewards of our kitchen garden are many. A big one had to be the first meal we prepared from plants we had started from seed and nurtured so carefully. It is such a pleasure when, in the depths of winter, our seed catalogs

arrive in the mail. We start all our plants from seeds selected primarily for their nutrition and flavor. As we read through the catalogs, making our selections, it’s as though we’re in our sun-drenched garden, smelling the mingled aromas of flowers and herbs.

Another reward is convenience. During the growing season we know there will always be a wide variety of the finest cooking ingredients waiting right outside the kitchen door. Because of the availability of seeds from around the world, and the success of our kitchen garden, it’s like bringing the Mediterranean markets home. If, in the course of our busy schedules, we end up at home with no meal planned and no grocery shopping done, we are still well provided. Some picking in the garden together with some easily stored staples and a little imagination will produce an enjoyable meal at least, and often a memorable one.

But more important, the garden has become a focal point of our home time. We enjoy tending it and picking from it. And just looking at it is a pleasure: seeing the plants grow and flower and set fruit, enjoying visitors like butterflies and dragonflies, and watching the birds hurrying back and forth between the garden and the nest. These are the things that enrich our lives.

Restoring a fragile ecology

Our kitchen garden not only had to fit the aesthetics of the landscape, it also had to fit its ecology. When we bought the property, it had been maintained by a lawn service that regularly sprayed a chemical cocktail of fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. As a result, there was little life in or above the soil.

I have always liked the term husbandman, with its two seemingly unrelated meanings of one who cultivates the soil, and one who manages prudently to conserve assets. But these meanings are not really unrelated since traditional cultivators of the soil also considered themselves managers of the soil, responsible for preserving its health. They knew the soil was a living thing, a fragile ecosystem upon which their livelihood depended. And they knew the soil’s ecosystem was part of, and dependent upon, the ecosystem above the soil. I felt that if this was the small part of the earth I would be managing, I had to find a better way.

I first set about building natural soil fertility. I shredded leaves into the lawn in the fall, and grass clippings followed in summer, along with supplements of organic fertilizer. This created an ongoing composting process that nourished the soil organisms, and they in turn nourished the grass.

I have found herbicides unnecessary. I consider weeds more of a resource than a nuisance. Decomposed weeds are the best source of many plant nutrients. The weeds outside the lawn I pull up by the roots and add to the compost pile. The mower takes care of high-growing weeds in the lawn, and the low-growing ones that survive are not necessarily unattractive. Many bear lovely flowers, and I leave these undisturbed. A large lichen-covered boulder, a gift from a retreating glacier, is embedded in the back lawn. We surrounded it with a circular bed of herbs and flowers, creating a little island in the lawn. Picking up on this theme, I planted problem spots in the lawn with low-growing, flowering perennials.

When the pesticide applications stopped, there were no predators available to keep the harmful insects in check, and infestations began. I controlled them by purchasing and releasing beneficial insect predators. Then birds and other native predators, finding the property a more hospitable environment, moved in and established a balance of nature.

by James Carr

February 1998

from issue #13

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in