Trees are a big deal. Once planted, they will change the garden around them and become the backbone of the landscape. They are the part of our gardens that will survive beyond us to impress and inspire future generations. On a more practical note, trees cool our beds, borders, and houses in summer; add value to our property; and remove pollutants from the air. In a world where garden space is shrinking, it’s easy to think that there is no room for trees. But landscapes without trees are like rooms without a ceiling. With a little searching, a huge selection of trees can be found that fit nearly any need.

Before you plant, be sure that you know how tall and wide the tree can grow, how much sun it will need, and what type of soil it prefers. Doing your homework will help you make the best selection. Most of all, though, choose a tree with “wow” factor. Great trees usually have at least one of the following traits: amazing blooms, extraordinary foliage color, or incredible texture.

Flowers provide focal points that are hard to beat

Three of the most widely planted trees are dogwoods (Cornus spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 2–9), crabapples (Malus spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9), and magnolias (Magnolia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9) because they all have spectacular blossoms. A relatively new introduction from the breeders at Rutgers University in New Jersey is Venus® dogwood. Its giant flowers can be up to 6 inches across, and they sparkle like the planet of the same name, which brightens the early-morning sky. This hybrid combines the best qualities of its two parents: Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa, Zones 5–8), with its excellent disease resistance to anthracnose and powdery mildew, and Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttallii, Zones 7–9), with its large flowers. Their offspring is a small charming tree with a rounded domelike crown. The gracefully layered branches are covered with huge blossoms, and even young trees bloom well. This hardy grower is quite adaptable and has performed well in both East and West Coast gardens—ideally, in partial shade. A 10-year-old tree will reach about 12 feet tall and wide, and in 20 years, it will be about only 18 to 20 feet tall and wide.

Magnolia is the queen of flowering trees, and in full bloom, nothing can rival its beauty. Although most magnolias are pink or white, years of selection and breeding have produced a few varieties that have showy yellow blooms; one of the most striking of those is ‘Butterflies’ magnolia. This elegant herald of spring has flowers 4 to 5 inches wide, which perch upright on the branches. Each petal is aglow with a bright lemon yellow, which fades to a soft primrose before dropping. The base of the bloom is flushed with chartreuse, adding a refreshing brightness. In the heart of the flower, the central stamens are red tipped in gold. ‘Butterflies’ magnolia is a small to medium-size tree, reaching about 15 feet tall in 10 years. It prefers full sun and well-drained soil. Occasionally, this magnolia will grow as a multistemmed specimen, although single leaders are more common.

If you want abundant blooms, crabapple is the tree to plant. Flowers cover the spring branches so densely that hardly a leaf or twig can be seen. The ability of crabapple to survive adverse conditions is nearly legendary. The biggest downfall is that many cultivars are susceptible to disease, so it is important to select proven, disease-resistant cultivars. One of the best is ‘Adirondack’ crabapple. The dark green foliage looks good from spring until the tree drops its leaves—which turn beautiful shades of gold, apricot, and orange—in autumn. The spring floral display starts with cherry red buds opening to large pure white blossoms scented with a light, fresh apple fragrance. This tree makes a great street tree—as long as it gets full sun and well-drained soil—and fits well into small urban gardens due to its unique, vase-shaped form. It will get 15 to 18 feet tall but only 12 feet wide. In early fall, tiny marble-size rose-red apples hang from the branches well into winter, waiting to be plucked and eaten by hungry birds.

Colorful foliage offers multiple seasons of interest

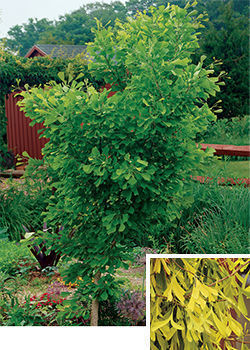

Choosing a tree with interesting foliage will provide a solid backbone to your landscape from spring through fall. The king of all foliage trees is the purple-leaved beech (Fagus sylvatica cvs., Zones 4–7). This stately giant needs large spaces to be fully enjoyed, but there are options for the gardener who has an average-size lot. The tight, columnar habit of ‘Dawyck Purple’ beech provides the lusciously colored foliage of its larger parent—which can reach upward of 80 feet tall and 50 feet wide—but only needs a fraction of the space. Named after the Dawyck Estate in Scotland, this noble tree bursts into leaf with shocking red wine tones (inset photo, above), but by early summer, it deepens to a sultry burgundy purple. Once the leaves drop in autumn, a distinctive wavy pattern to the upright branches is revealed. This tree can live for centuries, but it matures slowly. A 10-year-old plant sited in full sun to partial shade and well-drained soil might be only 18 to 25 feet tall with a slender spread of 6 feet.

If purple is not your color and you are into weird and wonderful options, track down ‘Wisselink’ variegated horse chestnut. In midspring, large and sticky buds burst open releasing luminescent primrose yellow leaves. These glowing leaves gradually expand, fading to a pale minty white etched with deep green veins by early summer. The delicate foliage can burn, so site the tree away from the hot afternoon sun; open shade is the preferred location. The lack of chlorophyll in the pale foliage makes ‘Wisselink’ a slow grower. In mild climates, this variety can even be grown for a number of years in a large container. When planted in the garden, expect ‘Wisselink’ to reach about 12 feet tall and wide in 10 years, with a mature tree reaching 20 feet tall and wide in as many years.

Gaudy can be good, and few trees can match the flamboyant show of ‘Esk Sunset’ sycamore maple. Discovered as a brilliantly variegated seedling in the Esk Valley in New Zealand, it was quickly shared around the world. (In North America, it is sometimes labeled by the eminently more marketable nickname ‘Eskimo Sunset’.) In spring, salmon-colored leaves emerge speckled with flecks of green. A few weeks later, the leaves become bright pink. By early summer, the underside of the foliage deepens to a burgundy red. Through the remainder of the season, leaves splashed with white, pink, burgundy, and green dazzle passersby. Best when grown in full sun to partial shade and well-drained soil, ‘Esk Sunset’ sycamore maple will reach about 15 feet tall and 10 feet wide in 10 years. At maturity, it will likely reach heights of about 25 feet tall. In some areas within the United States, the straight species, Acer pseudoplatanus*, has been declared an invasive species, so check with local experts before planting this cultivar.

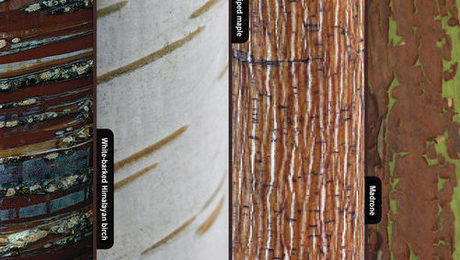

Eye-catching texture is unexpected yet makes an impact

A nontraditional way to add texture to the garden is with trees. Although we don’t often think of these woodies as having noteworthy texture, some do. A classic option with a ruffled appearance is ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba, Zones 5–9). The unique fan-shaped foliage is immediately recognizable. Ginkgo is well known for tolerating poor soils and tough urban conditions. But over time, most ginkgos become quite large; in addition, female trees bear messy fruit with an unpleasant smell. Fortunately for gardeners, there are many exceptional options of nonfruiting male trees, one of the best being ‘Saratoga’ ginkgo. The foliage of this California selection resembles a narrow fan, with the leaf only half the width of typical ginkgo foliage. In autumn, ‘Saratoga’, like its siblings, will turn a glowing golden yellow and drop most of its leaves at one time. This smaller and more compact form will slowly reach 12 to 15 feet in 10 years and about 25 feet in height with a similar width in 20 to 30 years.

The delicate texture of finely cut foliage is especially hard to find in a tree. Two of the finest exceptions are feather-leaf oak and imperial alder. Feather-leaf oak is a slow grower, only reaching 8 to 10 feet tall in 10 years and taking 20 to 30 years to reach 20 to 25 feet tall. As with most oaks, it has a stately habit that showcases the large beautifully cut leaves. The feather-leaf oak has a tropical appearance, with new growth emerging in late spring with pinkish white fuzz. Imperial alder is easy to grow and will quickly reach a height of 20 to 25 feet in 10 years. The lacy leaves create a fine green haze on smooth gray branches. As with most alders, imperial alder is tough and will tolerate wet and dry soil.

This handful of choice trees provides a sampling of what can be found with a little investigation. Using flowers, foliage, and texture as your guidelines will help you create an interesting garden for not only yourself but also generations to come.

The First Year Can be Tricky

If you decide to buy one of these amazing trees, then you’ll need to ensure that it gets off to the right start. According to a Clemson University survey, nearly 50 percent of all newly planted consumer trees die within the first year. It’s true: A lot can go wrong in the first year. Here are some things that you should—or shouldn’t—do to protect your investment and ensure its health:

Avoid transplant shock

Transplant shock occurs when a plant experiences extremes in its environment when newly planted. There are a few things you can do to prevent this. Avoid planting before spells of hot weather or before a hard freeze. Be sure to provide adequate water right after planting, and water carefully for the following few weeks. Also, take care to plant the tree at the proper depth: You should be able to see the beginning of where the roots flare out. If you do not, it may be planted too deep.

Site it correctly

Think about the future and how big the tree will get as it matures. Most nursery tags list a 10-year height, so expect your tree to get bigger than the label. Watch your exposure, too. Some trees need full sun, while others prefer some shade. Take note of the light levels of where you are planting to get the best flowers and foliage.

Don’t prune

Let a tree become established for the first year or two. Once the roots have taken hold, you can prune it to establish good structure and form.

Mulch—but not too much

A light layer of mulch will keep the moisture level even around the roots and help cool the soil during hot weather. Apply a 1- to 3-inch-deep layer of mulch, and keep it away from the trunk of the tree.

Provide supplemental water

Regular deep watering the first two to three years of a newly planted tree’s life makes all the difference. A general rule is for every inch the trunk is wide to add a year for the tree to become established. A small low berm of soil 1 to 2 feet from the trunk of the new tree will help water soak down to the roots (photo, above). Or if you have the resources, use drip irrigation. Most new plantings need weekly watering during dry weather.

Forget the fertilizer

During year one, a tree is busy growing new roots and becoming established. Much of the fertilizer applied during this first year is washed away or worse—it feeds nearby weeds. Fertilizers can be applied the second year with better results. Generally after four to five years, fertilizer is rarely necessary.

Richie Steffen is curator of the Elisabeth Carey Miller Botanical Garden in Seattle, Washington, and chair of Great Plant Picks, an educational program that recommends outstanding plants for Pacific Northwest gardens.

Photos, except where noted: millettephotomedia.com

The following mail-order plant sellers offer the widest selection of the trees featured:

- Broken Arrow Nursery, Hamden, Conn.; 203-288-1026; brokenarrownursery.com

- Forestfarm, Williams, Ore.; 541-846-7269; forestfarm.com

- Variegated Foliage Nursery, Eastford, Conn.; 860-974-3951; variegatedfoliage.com

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in