Mustard is an ancient plant that’s full of appeal for contemporary gardeners. The plants are easy to grow and produce seed in as few as 60 days. The greens are edible, the flowers attractive, and if the seeds are allowed to mature on the plant, they will self-sow and still provide plenty for mustard making. Is making your own mustard worth the effort? Considering that a small jar of good Dijon can cost up to $6, it is indeed. About a dollar’s worth of seed will produce a pantry shelf full of fine and fancy mustards and more greens than you can shake a salad spinner at.

|

||

| Mustard is a tiny seed with a lot of spunk. It will grow just about anywhere, is rarely bothered by pests, and is prolific to boot. | ||

Mustard in all its forms—shoots, leaves, flowers, whole seed, powdered, or prepared—is a flavorful, low-fat way to punch up any savory food. I’ve used the whole seed in pickling and cooking, tossed the tender greens in fresh salads (garnished with mustard flowers, of course), stewed mature leaves as a southern-style side dish, and crushed spicy seed to make a variety of pungent mustards.

If you’ve ever traveled to California’s wine country in early spring, you may have seen the vineyards awash in yellow flowers. Those are mustard plants, the winemaker’s friend. Many vineyard owners plant mustard deliberately as a cover crop or let field mustard (Brassica kaber) run rampant. When plowed back into the soil, the plants act as a green manure and release nitrogen. Mustard also repels some insects (the seeds are that hot) and attracts syrphid flies, beneficial predators that attack vine-chewing insects.

Mustard seed contains no cholesterol, only trace amounts of vegetable fat, and about 25 percent protein. Leaf mustard contains calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and Vitamin B. The calories are negligible in most basic prepared mustards, so you can feel free to indulge.

Today, mustard is second in demand to pepper among spices in the United States. Historical records indicate the use of mustard as far back as 4,000 b.c.e., and it’s believed prehistoric man chewed mustard seeds with his meat (probably to disguise decay). From about 2,000 b.c.e. on, ancient civilizations used it as an oil, a spice, and a medicinal plant. It was introduced into western and northern Europe in the early Middle Ages.

Over the years, mustard has been imbued with curative powers. It’s been called an appetite stimulant, a digestive aid, and a decongestant. Because mustard increases blood circulation, it’s often used in plaster form to treat inflammation. Folklore has it you can even sprinkle mustard powder in your socks to prevent frostbite.

All mustards come from the Cruciferae, a family that includes broccoli and cabbage. Brassica nigra, B. alba, and B. juncea produce black, white (really a yellowish-tan), and brown seeds, respectively. The black seeds of B. nigra are used for moderately spicy mustards. French cooks use them to make Dijon-style mustard—it can be called true Dijon mustard only if it is certified to come from that city, which has the exclusive right to produce it. In West Indian dishes, black seeds are fried until they pop. The black variety produces less-desirable greens, and is really intended to be grown for seed.

White seeds—B. alba—are the primary ingredient in traditional ball-park mustard, and it’s the most common and the mildest of the three. The white seeds also have the strongest preserving power and are therefore the kitchen gardener’s choice for pickles, relishes, and chutneys. White mustards are not typically grown for their greens.

Brown mustard, the hottest of all, is used for curries and Chinese hot mustards, and frequently for Dijon-type mustards. If you’re growing mustard for the greens, choose B. juncea or an Oriental variety like ‘Giant Red’.

Mustard is easy to grow

Mustard will grow well in most soils, but will produce the most seed in rich, well-drained, well-prepared soil with a pH of no less than 6.0. It will thrive if given constant moisture. It likes cool weather; a light frost can even improve the flavor. Black mustard is the least fussy.

|

||

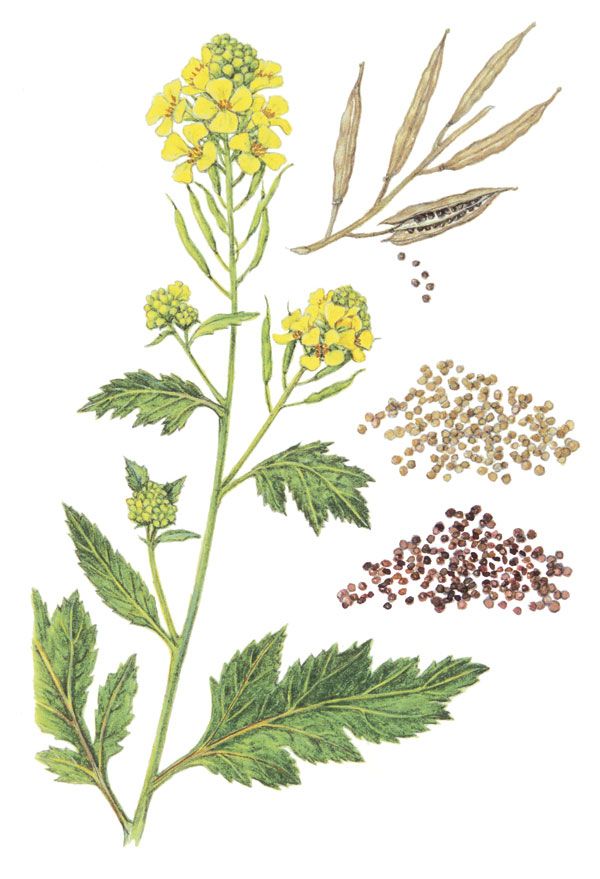

| The black mustard plant (Brassica nigra), shown with a mature seed pod (top right), white mustard seeds, and black mustard seeds. | ||

For best results, add 10 to 15 pounds of 5-10-10 fertilizer per 500 square feet, or the organic equivalent. Thoroughly work the amendments into the top 2 to 3 inches of soil just prior to seeding.

In the springtime, sow the seed in drills about 1⁄8 inch deep and 15 inches apart, as the last frost deadline nears. If you live in the South, you can also seed in September or October for harvest in the fall and winter. Once the plants are up, thin to 9 or 10 inches apart, and then you can almost ignore them. If you’re interested in harvesting a lot of seed, however, feed the plants regularly.

Mustard is blissfully free of insect and disease problems, and larger critters don’t seem to like it much either. The hotter and drier the weather, though, the faster the plants go to seed—30 to 60 days, depending on the variety and the climate.

Cutting the mustard

Pick B. juncea leaves for salad when they’re small, young, and tender, or use the larger leaves for sautéing or stewing. Add young leaves to stir-fries and salads. Mustard greens add a nice, sharp flavor contrast to mild, buttery lettuces and therefore are often one of the plants found in mesclun mixes.

| Mustard in the kitchen:

• How to Grind Mustard Seeds and Make Mustard Mustard recipes: |

|

Larger mustard leaves need to be cooked. Stew them with bacon or a ham hock, southern-style, or shred and sauté them with other greens to make a bed for grilled fish and meats. You can also add mustard greens to long-cooking soups and stews. Flowers can be used as an edible garnish.

Watch out if you let the pods get too ripe, or your garden could become overrun with mustard plants, which may be exactly what you want. If you want to harvest seeds, however, pick the pods just after they change from green to brown, before they are entirely ripe; otherwise they will shatter and the fine seed will blow into every corner of your garden.

Pods should be air-dried in a warm place for about two weeks. Spread them out on clean muslin, an old sheet, or a fine screen. Once dry, gently crush the pods to remove the seeds and hulls.

| Mustard, the greatest among herbs |

| Mustard is an ordinary-looking little seed with an impressive ability to grow into a mighty plant that’s highly prolific. Its reputation as both a seed with great promise and great piquancy is supported by numerous passages found everywhere from the Bible to Shakespeare.

How could this small nothing-of-a-seed attract grandiose praise and literary attention? Through tenacity and vigor, no doubt. See the passage below from the Book of Matthew for an example of these traits. After reading the passage, you might question whether mustard could ever attain the stature suggested. Yes, it is possible that Brassica hirta and B. nigra grew into trees in the Mediterranean climate. The kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field, which indeed is the least of all seeds. But when it is grown, it is the greatest among herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches thereof. |

by LeAnn Zotta

February 1997

from issue #19

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in