Nine years ago, we stumbled upon the piece of land that would become our future home: a huge cornfield, with the corn 7 feet high. The surrounding fields that stretched out before us were a patchwork, some planted in corn and others in alfalfa. There was a big red barn with six silos in the foreground. Beyond the iconic barn, the fields were intersected by occasional lines of trees disappearing into foothills on the horizon.

The fields we saw in every direction were established within straight lines—even the barn in the distance was long and linear. Everywhere humans have settled, straight lines have been laid down, either consciously to stay within regular borders or subconsciously to show nature that humans have an intention of bringing order—at least for a time—to their surroundings. So it was to be with our home and gardens: The house would be long and linear, and like the barns in our area, it would have a tower, like a silo. The garden that would stretch out north, south, east, and west from the house would follow straight lines, like the fields in the distance.

These straight lines, which might be considered out of step with such natural surroundings, actually help connect the house and garden to the larger landscape. Within these lines, we’ve used plants that soften the rigidity of the design and further connect the garden to its surroundings.

Two main lines form the backbone of the garden

All sight lines and paths are related to the two main axes, while columnar shrubs and billowy grasses are used to both emphasize and soften them. Visually, this creates a sense of relaxed order, which mimics the fields surrounding the property. Physically, these lines keep you focused and aware. Rather than the mystery that curved paths and beds add to a garden, straight paths allow you to focus on your surroundings, not the next step you’ll take.

A series of sight lines and paths echoes the lines of the house

Upon entering our front door and turning to the right, your eye travels the length of the house, through a glass door, and out onto a grass path. This path stretches 100 yards to a blue earthen pot, signaling the end of the garden. This main axis inextricably connects the garden and house. It also guides you out to the garden and back to the house.

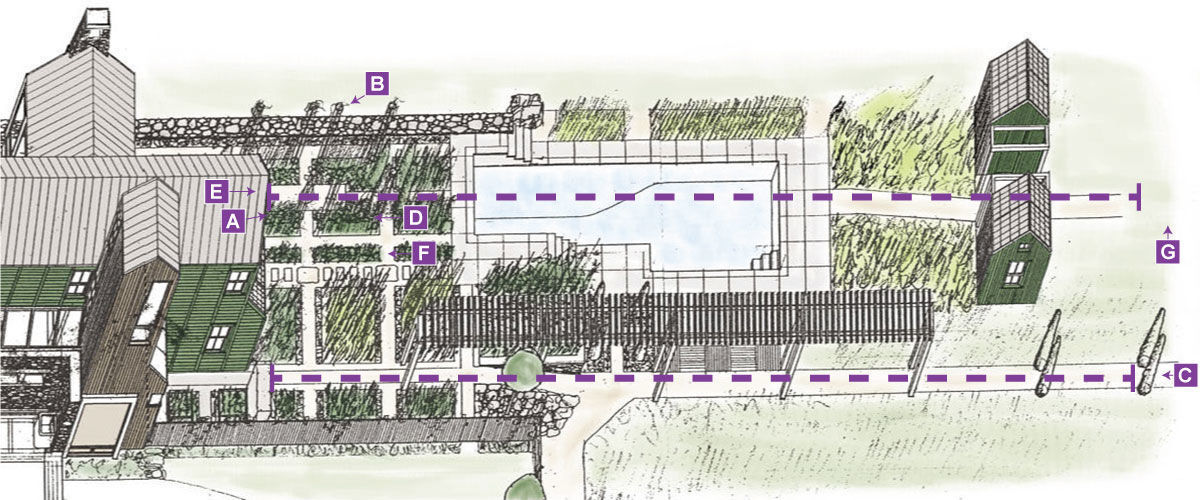

Proceeding through the house from the front door, you pass through the dining room, skirt the kitchen, and enter a glassed-in porch. The views here are not only of the red barn and its six silos but also of the meadows and another main axis. This second axis is parallel to the first and runs by the garden and a large terra-cotta urn, a swimming pool, two pool houses, some solar panels, and a rill; it also ends at another iridescent blue pot. These two main lines are the organizing principle of this garden.

We chose to break these main lines with paths that cross these axes perpendicularly, creating a grid of intersecting lines. These stone or grass paths divide the garden into smaller units, and allowed us to plan gardens that are distinct from one another. The dimensions of each garden within the overall grid is some multiple of 4 feet, and this same approach is used for the house. Extending this grid gave us the ability to tie the house and garden tightly together and to vary the nature of each section of the garden, which might have been more difficult if the grid did not exist.

The two main lines emphasize the long, narrow nature of the garden, which matches the narrowness of the house itself. These lines and the crossing paths draw the eye outward to the meadows that surround the house and garden, and beyond to the acres of corn and alfalfa.

Plants accent straight lines and evoke the surrounding landscape

While the gardens are regular in their dimensions, a multitude of grasses sway in the slightest breeze, lending a free-form sense to the garden. One long set of gardens is based on grasses, which mimic the fields; another long set of gardens is based on perennials. Material in the grass and perennial beds is repeated, providing a transition from one garden to the next. And ideas are also restated. The color scheme of a grass-based bed, for example, may mirror that of a perennial bed by using plants of the same color.

Some of the grasses can grow as tall as 10 feet, which add a vertical aspect to the garden. We also use tuteurs and narrow trellises to support flowering vines, which lend color to the vertical dimension. We’ve introduced other exclamation points in the form of tall, narrow ‘Degroot’s Spire’ arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis ‘Degroot’s Spire’, Zones 2–7), a columnar evergreen tree that provides year-round interest. These sentinels reflect the straight lines of the garden, while the grasses and perennials echo the fields beyond the garden. Mixing the two types of plants connects the straight lines of the house to the free-form nature of the outer landscape.

Everything we’ve done in this garden has been to complement the amazing show that nature has provided in our fields and in the wide-open views that surround our home. If we have succeeded at this, we have, in our view, done a worthwhile thing.

What we really want to know is…

How do you take care of it?

We have two helpers; without them, we wouldn’t be able to do it. Maintenance is a killer, and we don’t plan to expand the gardens an inch. The bane of our existence is weeds. Some of the desirable plants, such as morning glory (Ipomoea tricolor and cvs., annual), tall verbena (Verbena bonariensis*, annual, above), and Korean angelica (Angelica gigas, USDA Hardiness Zones 4–9), are wonderful when they stay put but a real nuisance when they reseed. Being surrounded by fields of wildflowers and weeds means lots of seedlings show up where we don’t want them: in the gardens.

Is it sustainable?

We use organic materials wherever we can, and we compost extensively, with two large composting bins next to the pool houses and solar panels. In addition, all rain that collects on the roof of our house is captured and piped into two large cisterns. The irrigation system draws water from these cisterns, with backup from our well.

Do you ever disagree on design decisions?

We see things differently. Larry is an architect and thinks in terms of overall design and structure. Jack is more of a gardener and likely to become infatuated with a new plant. Jack struggles to remember that blocks of color or masses of plants are more important to the overall look than a couple of plants here or there.

Jack Hyland and Larry Wente tend their garden in Millerton, New York.

Photos, except where noted: Daryl Beyers. Site plan: courtesy of Larry Wente

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in