There is no denying that massing plants makes an impact. Many of the most compelling gardens (think Piet Oudolf’s High Line plantings in New York) feature masses of plants. Massing has played a big role in a couple of influential planting movements of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The New American Garden style of Wolfgang Oehme and James van Sweden, and the New Perennial Movement, championed by Oudolf, Noel Kingsbury, and others, immediately jump to mind. We know their names, and some of us can conjure up an idea of what their planting styles may look like. But more often when gardeners think of massing, they call to mind big commercial properties.

These spaces generally have large installations of some common plant that are surrounded by mulch. They look rigid and feel cold and impersonal—exactly the opposite of how we want our home gardens to feel. So how do you mass plants to create drama and impact without creating a landscape you’d find surrounding an office building? This was exactly the challenge we faced at Afterglow Farm, a private home in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin, where the gardens are spread over about an acre and a half around a sprawling stone cottage. We designed the planting beds to be large in order to make an impact within the 120-acre wooded property. But the visual punch really comes from our use of massing, which serves to simplify the design and create cohesiveness in these large beds. As a bonus, such massing offers reduced maintenance.

There is a time to mass, and a time to mix and mass

While a traditional mixed border (or any mixed planting) can look dramatic and exciting, it can also often seem busy or spotty. It takes considerable skill, knowledge, and experience to be able to combine lots of individual varieties of plants and achieve good design results. It is even more difficult to get a mixture of many varied plants that will look good from spring to autumn. The larger the garden, the more difficult it can be to pull off a mixed planting that always looks good. Massing can be part of the solution to these problems.

Massing of a single, standout plant variety can cover a large area of a garden without the fuss of having to match up plants with similar conditional requirements, or to be sure that the bloom colors of different varieties look good together. At Afterglow Farm we have a planting of astilbe (Astilbe chinensis, Zones 4–9) stretching 30 feet long and 7 feet deep under an arching pine tree (see photo, top). It makes a big statement, and it covers a lot of ground.

Massing also increases the impact of texture. In another area measuring about 30 feet long by 10 feet wide, we’ve grouped 26 clumps of little bluestem grass (Schizachyrium scoparium, Zones 3–9) behind more than 30 ‘Blue Wonder’ catmint (Nepeta ‘Blue Wonder’, Zones 3–8) and then included a smaller pocket of ‘Little Spire’ Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia ‘Little Spire’, Zones 5–9) between these two larger plantings. It’s impossible to ignore the fine textures of the grass and Russian sage above the denser mounds of catmint (photo, below). The fact that the foliage and bloom color of all these plants is similar only makes the waves of texture more impactful—especially when the wind blows. No one will use the words “spotty” or “busy” to describe such a scene.

Over time, however, my associate Christine and I have made changes to the original masses of plants to get more variety and to achieve more of an English mixed border look. We have played with the existing mass plantings, eliminating some, adding new ones, and splitting others up by mixing in new plants. The result is what I call “mix and mass.” An example of this concept is best illustrated in an area surrounding a large Austrian pine (Pinus nigra, Zones 4–7). The roughly 6-foot-deep and 30-foot-long spot was originally planted with mostly ‘Six Hills Giant’ catmint (Nepeta ‘Six Hills Giant’, Zones 3–8). To introduce more texture and height, we mixed in clumps of ‘Summer Beauty’ allium (Allium ‘Summer Beauty’, Zones 5–9), some ‘Becky’ shasta daisy (Chrysanthemum × superbum ‘Becky’, Zones 4–9), and a few clumps of ‘Blue Star’ kalimeris (Kalimeris incisa ‘Blue Star’, Zones 5–9) in multiples of three and five. This meant that we kept some of the existing mass of the long-blooming catmint but added even more interest by mixing in smaller masses of other plants.

Choose the right plants

Another reason that massing in commercial landscapes may often seem uninspired has to do with the type of plants used. Daylilies, carpet roses, and certain ornamental grasses can be really useful when planting in difficult circumstances, but they have become ubiquitous. And while it is always good to choose the right plant for the conditions, why not use something a little more unexpected?

At Afterglow Farm, we use many different plants for massing. So while you will see large plantings of more typical ‘Goldsturm’ black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia ‘Goldsturm’, Zones 3–9) and ‘Karl Foerster’ feather reed grass (Calamagrostis × acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’, Zones 5–9), we also mix it up with many other choice perennials, such as alliums, Shavalski’s ligularia (Ligularia przewalskii, Zones 4–8), and ‘Autumn Bride’ heuchera (Heuchera villosa ‘Autumn Bride’). Much of the plant choice at Afterglow is also determined by what can withstand the deer browsing. In gardens where size allows, use masses that bloom at different times. This can shift the focus of attention around the garden as the season plays out. We’re able to spread the bloom time in certain areas from midspring through the end of summer. When using multiple masses of plants in the same area, it is important to consider any overlapping bloom time to create pleasing color combinations or contrasts, depending on your intent. The other consideration with multiple massing in an area is to use plants that have a long flowering period and/or are interesting even before or after bloom. In our gardens, a mass of ‘Brunette’ bugbane (Actaea simplex ‘Brunette’, Zones 4–9) makes an impact all season long. The dark-leaved ‘Brunette’ is attractive in spring when paired with purple columbine (Aquilegia vulgaris, Zones 4–9) and chartreuse-flowered lady’s mantle (Alchemilla mollis, Zones 3–8). Later in summer, the grouping still looks good next to white-flowered meadowsweet (Filipendula cv., Zones 3–9). These combinations all occur before the bugbane itself finally blooms in early autumn.

How you lay them out matters

The way you plant your masses can mean the difference between a garden that looks corporate and one that looks stylish. Often the use of massing in a commercial landscape can look stiff or regimented because planting is done in linear rows with regular spacing within geometric-shaped areas. Plant spacing matters, and we often plant with much tighter spacing than recommended. We generally don’t use linear placement. Instead, we place plants irregularly within the designated area, spacing them off of each other in any direction. We consult the nursery tag for recommended spacing, but we generally eyeball the design rather than using a measuring tool. We purposely create masses with irregular borders, bending and blending the edges. Masses take on amoeba-like shapes without right angles or straight lines. The result is a much more natural and dynamic look, as the eye tends to follow these shapes in and out, resting less and instead looking for patterns. Plant-spacing guidelines are just that: guidelines. You should also use your experience or intuition about how closely you want the plants to grow.

The way you lay out the plants can also affect whether or not you reap the benefits of reduced maintenance that massing can offer. Laying individual plants out in large, closely grouped plantings can mean less space for weeds to grow and less need for mulch. For example, we plant a mass of ‘Blue Wonder’ catmint at approximately 16 inches on center rather than following the recommended 24-inch spacing. This means that the plants bump into each other and cover all the ground between them. We usually give the catmint a trim after the initial bloom to freshen and promote a second flush of flowers anyway, and that prevents too much overlapping.

Another way that massing reduces maintenance time is in consolidation of effort. In a planting that uses a wide variety of different plants, each plant type may have separate needs for deadheading, deadleafing, pinching, cutting back, structural support, pest control, and watering. If you cover more area with the same plant, you can streamline the maintenance by performing one task repeatedly and taking advantage of the efficiency of scale.

Massing provides cohesion and simplifies a design while making a big impact in your garden both visually and in terms of maintenance. Choose plants that work in the conditions you have and that have more than one season of interest—and think beyond the usual suspects. Why plant three when 23 would work? Sometimes more is more.

Design

Mass by Numbers

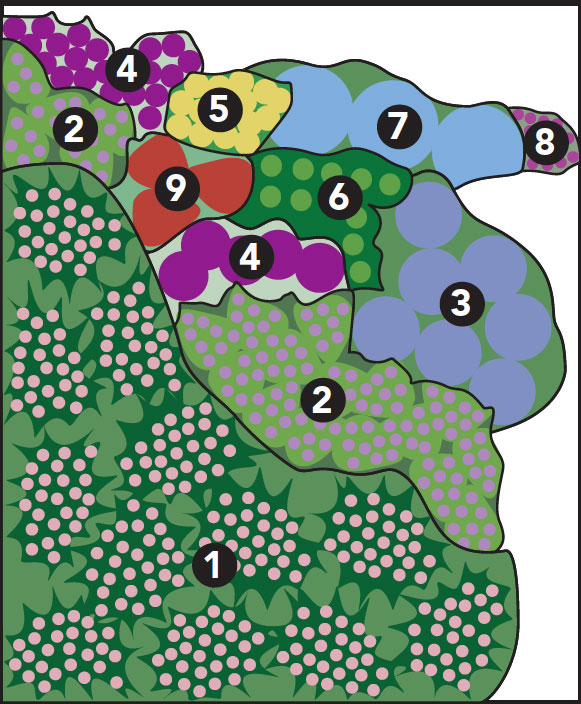

When you’re first planting your masses, it can be hard to envision how many plants to include and how close to install them. This part of the garden was originally designed by Judith Stark about a year before I came to Afterglow Farm. Although it has changed quite a bit since then, it’s a good example of what the masses in one area of the garden look like in a planting plan (below) and what the garden looks like all filled in several years later.

1. ‘Peach Blossom’ astilbe

(Astilbe × rosea ‘Peach Blossom’, Zones 4–9)

12 plants

2. Winter Glow bergenia

(Bergenia cordifolia ‘Winterglut’, Zones 4–8)

First group: 15 plants; Second group: 5 plants

3. ‘Blue Wonder’ catmint

(Nepeta racemosa ‘Blue Wonder’, Zones 3–8)

7 plants

4. ‘Kobold’ blazing star

(Liatris spicata ‘Kobold’, Zones 3–8)

First group: 5 plants; Second group: 21 plants

5. ‘Moonshine’ yarrow

(Achillea ‘Moonshine’, Zones 3–8)

15 plants

6. Prairie dropseed

(Sporobolus heterolepis, Zones 3–9)

11 plants

7. Blue star

(Amsonia hubrichtii, Zones 5–8)

3 plants

8. Bloody geranium

(Geranium sanguineum, Zones 3–9)

15 plants

9. ‘Brookside’ geranium

(Geranium ‘Brookside’, Zones 5–9)

3 plants

Dean Wiegert is the head gardener at Afterglow Farm in Wisconsin.

Photos: Danielle Sherry

More on mass planting

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in