Wisteria is a vine that has always intrigued me, with its distinctive growth and flowering characteristics and its capacity to thrive almost anywhere. It’s a familiar, fragrant landscape component in gardens worldwide, with flower colors ranging from white to shades of pink, blue, lavender, and purple; the racemes of some types can drape as much as 3 feet in length. Depending upon the species and cultivar, flowering initiates in the first warm spring days, with some types continuing into summer and even later, given the right conditions.

Since wisteria is a legume, its root system fixes atmospheric nitrogen, enabling it to establish and grow well even in the poorest soil. Few plants I know can put on new growth so rapidly and rampantly, a major benefit for many landscape applications. Wisteria is pest resistant and has clean foliage that creates alluring curtains of greenery when properly supported, effectively screening unsightly views. It’s also deer resistant and friendly to pollinators such as butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds.

In addition to its positive virtues, though, some drawbacks need to be considered before welcoming wisteria into a garden. All species produce runners at their base that travel along the ground for many feet, rooting-in where each node touches the soil. Branches can rapidly cover the ground or aggressively wind around structures (and pull them down), growing as much as a foot a day in midsummer. Left untended, a single plant can soon become a thicket and a nightmare to manage. Most species produce abundant amounts of seed, which burst forth when mature from beanlike pods to readily germinate, even at a distance from the parent plant.

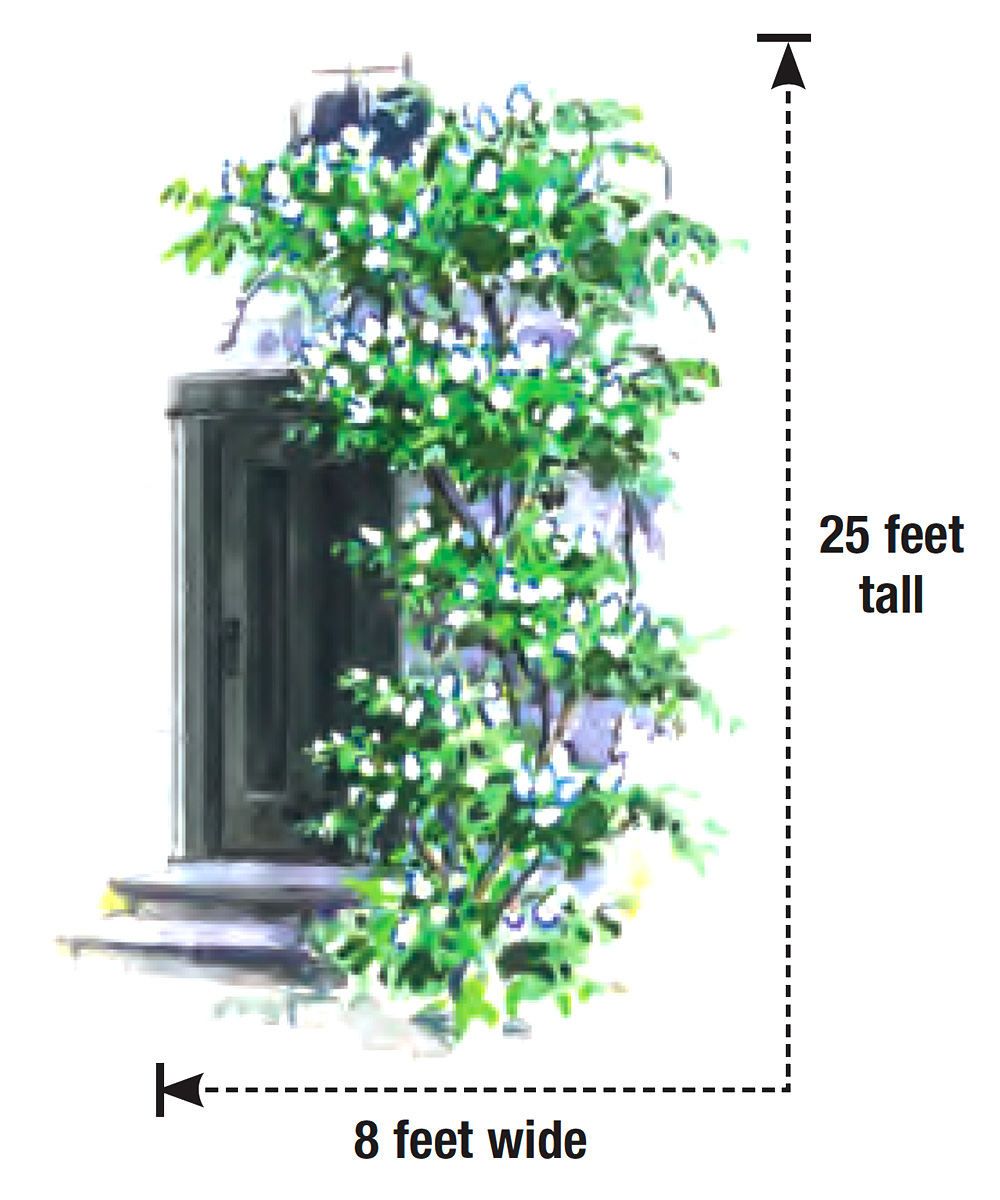

The native Kentucky wisteria (W. macrostachya, Zones 3–9) and all the Asian types can dominate the area where they’re growing and typically require serious maintenance several times a year to keep them in check. Happily, there’s a native species that performs with more dignity: the American wisteria (W. frutescens and cvs., Zones 5–9). This species normally reaches less than half the size of other species, typically maturing at around 25 feet tall. Although still vigorous, American wisteria grows more slowly and even tolerates a bit of shade, albeit with reduced flowering. As with other species, cutting back to three to four buds on each stem each spring helps keep it in check, and periodic summer pruning is recommended, along with continuous removal of basal shoots.

American wisteria is a fine choice for smaller gardens and will grow well in a container above ground, making it potentially a portable landscape element. My favorite cultivar is the white-flowering form ‘Nivea’, reportedly discovered in the wild by Mary Gibson Henry, founder of Pennsylvania’s Henry Foundation. Surprisingly ‘Nivea’ is less commonly seen at garden centers than the more popular purple cultivar ‘Amethyst Falls’. It produces a profusion of densely packed, fragrant, fist-size flower clusters in May, right after its fine-textured pinnate foliage appears. Given the right conditions, it will continue flowering sporadically all summer.

‘Nivea’ wisteria

Wisteria frutescens ‘Nivea’

Zones: 5–9

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; adaptable to a wide range of soil types

Native range: Eastern North America

Wayne Mezitt, a third-generation nurseryman and Massachusetts Certified Horticulturist, is chairman of Weston Nurseries and owner of Hort-Sense, a horticultural advisory business.

Illustration: Elara Tanguy

Sources

- Brushwood Nursery Kennett Square, PA; brushwoodnursery.com

- Woodlanders, Aiken, SC; 803-648-7522; woodlanders.net

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in