You know how sometimes at a party or dinner there is that one super-extrovert who so totally dominates the conversation that it is hard to notice or get to know anyone else? In the genus Iris, the role of that slightly overbearing, loud personality is played by the bearded irises. Big, flamboyant, and numerous, beardeds can make it hard to get to know the many other irises worth growing. So let’s pause, go to a quieter room, and take a moment to appreciate the other irises. You won’t regret making their acquaintance.

Reticulata irises are the first to bloom

If you hate waiting for spring to arrive and want early flowers, the default option is to plant snowdrops. Please don’t. Yes, snowdrops are early, dainty, and charming, but they’re also tiny and a bit boring. They’re all green and white—or occasionally, in what passes for a radical color break in snowdrops, yellowish green and white. I know there are galanthophiles who spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars for special, rare snowdrops, but let’s be real: The only reason to grow snowdrops is that they bloom so early. If they looked the same but flowered in May, none of us would have ever heard of them.

Now consider by way of contrast the reticulata group of irises. In northern climates, these little irises bloom at the same time or just slightly later than snowdrops, but no one can accuse them of relying on that early bloom window. These are beautiful, colorful, intricate, fragrant blooms you’d be thrilled to have in the garden any month of the year. The fact that they bloom the instant the snow melts and can take a few inches of new snow on top of those flowers without missing a beat puts these little irises firmly in the must-have category.

The reticulata group is a section of closely related irises that grow from little bulbs, called reticulata for the way they are covered with a netlike—that is, reticulated—jacket of fibers. Why these beautiful little plants are named for the least interesting of their features is beyond me; you’ll have to ask the botanists. But whatever the name, several species and cultivars of reticulata irises are widely available. All of them are beautiful, but two are my absolute favorites.

‘George’ (I. histrioides ‘George’, Zones 3–8) is always on the top of my list of reticulatas, for one simple reason: I have planted masses and collections of every reticulata I could find in many different gardens in various parts of the country and have consistently found ‘George’ to be the most vigorous, the one that perennializes, multiplies, and puts on the best show year after year. Its flowers are a rich, dark shade of purple marked lightly with gold and blessed with a delicious scent. The one flaw with ‘George’ is that its dark flowers can disappear in the garden, particularly if they are growing against a backdrop of dark mulch. To get the most from this variety, plant it in front of a light-colored rock, or surrounded by yellow aconites (Eranthis hyemalis, Zones 5–8) or white snowdrops. Placing ‘George’ on a light background shows off its darker hues to perfection.

My other favorite reticulata is ‘Katherine Hodgkin’ (I. ‘Katherine Hodgkin’, Zones 5–8), which is a hybrid between purple I. histrioides and pale yellow I. winogradowii. Each bloom is a complex work of art whose pale, near white petals are covered with a fine network of blue lines and a blaze of contrasting yellow. ‘Katherine Hodgkin’ is stunning in masses, particularly when grown in a container or raised rock garden where you can easily get up close and appreciate every perfect line and detail of its form. While doing so, you will also discover a sweet scent that comes out the strongest on warm and sunny spring days. It is worth noting here that reticulata irises are easily forced into early bloom indoors, and ‘Katherine Hodgkin’ is the perfect choice for that. If you force it into flower while there is still snow on the ground, you will revel in its every detail, and the indoor warmth will bring its fragrance out in an entirely pleasing way.

The members of the reticulata iris group thrive best in well-drained soil where there is access to plenty of sun in early spring while their foliage is ripening. When I’ve gardened on wet, heavy clay soil, I find that they tend to bloom their first year and then fade away (except ‘George’, which is always a trooper). On sandier soils, they thrive and multiply (with ‘George’ again leading the charge). But if you have clay soil, don’t despair. All you need to do is build up a raised bed or rock garden using sharp sand or a mix of sand and gravel over your clay soil, and plant in that. That well-drained surface layer is what these little bulbs need to thrive and come back stronger year after year. Reticulata irises are very cold hardy, thriving all the way up into Zone 3, and they bloom well even in the minimal winter chill of Zone 9.

Think of Dutch irises like tulips

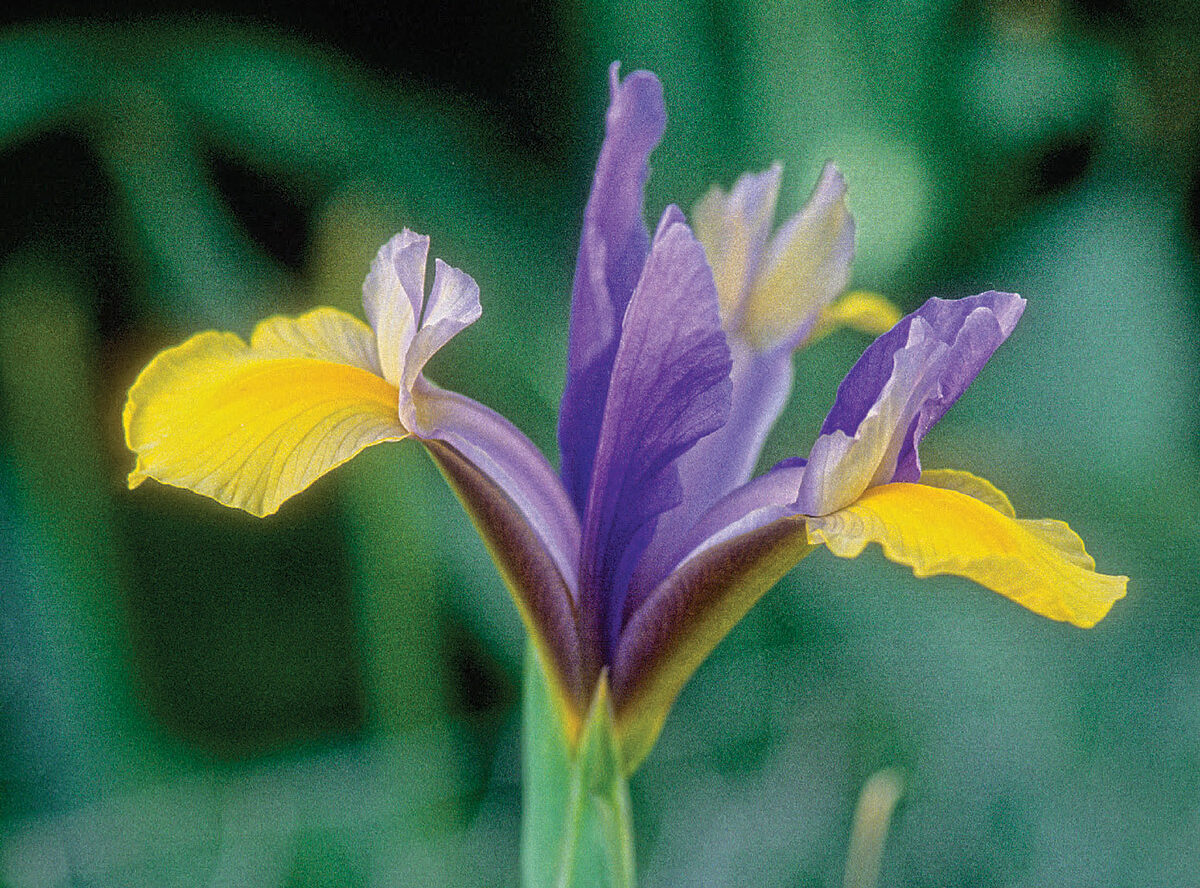

Other lovers of well-drained, sandy soils are the bulbous Dutch irises (I. × hollandica cvs.). These irises are derived from hybrids of I. xiphium, I. tingitana, and I. latifolia, all of which are native to sunny Spain. The best way to think of this group of irises is like another group of plants from warm, sunny climates that have long been cultivated in Holland: tulips. Like tulips, Dutch iris bulbs are cheap and easily available in fall; they bloom around the middle of tulip season in spring. They are equally suited to massive displays in a garden or a vase, and like tulips, they’re generally best thought of as annuals because they tend to fade away in most climates after their first spring show. But, again like tulips, that is absolutely no reason not to grow these beautiful plants. You can plant them in masses for spring color, then replace them with summer annuals once the blooms fade, or you can stick a row in the vegetable garden to cut for vases in the house and then replace them with tomatoes and peppers for the summer.

If you do want to encourage these bulbs to perennialize, the key is to give them a dry summer dormancy. Sandy, well-drained, unirrigated soil is best, whether that occurs naturally in your garden or you make a raised bed with that type of soil. Most references list Dutch irises as being hardy in Zones 6–9, although I grew them for many years in my Zone 5 garden in Michigan with no problem.

There are many widely available selections of Dutch irises, but you can’t go wrong starting with ‘Oriental Beauty’ (I. × hollandica ‘Oriental Beauty’, Zones 5–9). Each bulb sends up a strong, 2-foot-tall stem topped with flowers featuring rich blue standards and contrasting soft yellow falls that make for the most sophisticated celebration of spring possible. Combine these flowers with icy white tulips in the garden or in a vase, and you will be a very happy gardener indeed.

For a little more drama, try ‘Eye of the Tiger’ (I. × hollandica ‘Eye of the Tiger’, Zones 5–9), which has standards of rich purple and coppery, red-brown falls, each of which is marked with a bold spot of bright yellow—the “eye” from which the variety gets its name. The color combination looks incredibly sophisticated and pricey but, happily, is actually inexpensive.

Japanese irises are the prettiest water irises

Not all irises like dry conditions. If you have clay soils, live in a rainy climate, or garden in a low, wet spot, bearded irises may pout and get innumerable fungal diseases on their leaves, and the bulbous species I just described will bloom once and then fade away. But there are many irises that love wet conditions. Often called “water irises,” these irises will grow happily in anything from shallow standing water at the edge of a pond to normal garden soil that is well watered by irrigation or regular rainfall.

As part of a group of serious and talented professional gardeners, nursery people, and writers, I was recently invited to a dinner party at the home of an avid gardener. The guests had seen it all when it comes to garden plants; you might even call us jaded. But when one guest arrived with a vase full of perfectly grown Japanese iris flowers, we all gasped. Japanese irises are so huge, so perfect, and so beautiful that you can scarcely believe they are real.

As is obvious from the name, these irises come from Japan, where they’ve been bred for over 400 years from the wild species I. ensata. In Japanese culture, these are very special plants, with a rich culture built up around enjoying the details of the flowers in display gardens, and in pots and vases indoors.

Culturally, Japanese irises are prima donnas. They’re not that difficult, and they don’t have many severe disease or pests, but they demand acidic, richly fertile soil either with shallow standing water or in a moist, regularly watered part of the garden. But a little extra water and fertilizer is a small price to pay for these incredible blooms.

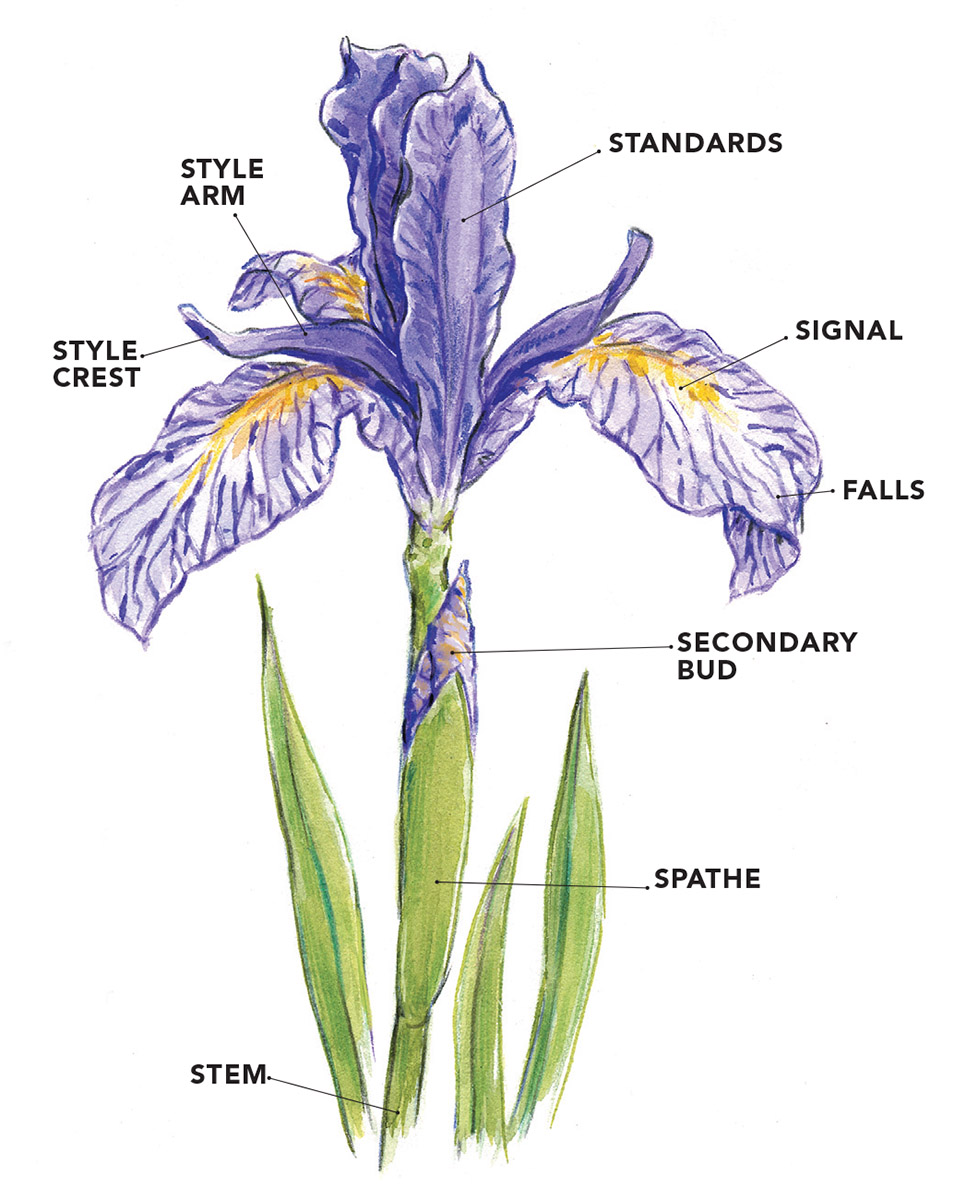

‘Snowy Hills’ (I. ensata ‘Snowy Hills’, Zones 5–9) is one of the classic Japanese irises with six falls. Irises have two types of petals; in nearly all species, there are three falls, which hang down from the flower, and three standards, which stand upright. Most varieties of Japanese irises have been bred so that they have six falls and no standards, so instead of that typical iris look of contrasting upright and trailing petals, all six falls open out flat or hang down to create a huge, flat flower. On ‘Snowy Hills,’ those blooms can be fully 6 inches across, with each petal bright white with a dab of bright gold, called a signal, at the base of each petal. As incredible as these massive blooms are in the garden, be sure to cut some to display in a vase as well. They are one of the only blooms that can rival peonies for sheer opulence as a cut flower.

The massive, perfect blooms of the six-falled Japanese irises are beautiful, but they aren’t for every garden. They are the pinnacle of hundreds of years of careful design and creation by plant breeders, and it shows. If you favor a more naturalistic, informal design, they may look a little out of place. If you want a plant that is still beautiful but might look more at home at the edge of a small pond mingling with some cattails, consider a three-falled variety such as ‘Blue Embers’ (I. ensata ‘Blue Embers’, Zones 5–9). Still astonishingly beautiful, they are more similar to what the Iris ensata looked like before plant breeders started redesigning it. The flowers are still large, exquisitely colored, and perfect for cutting for the vase, but they also retain a little wildling charm and naturalistic grace.

Louisiana irises offer a range of color

In contrast to the long history of breeding Japanese irises, Louisiana irises are newcomers. As the name suggests, they are hybrids of a group of five species of water irises native to Louisiana and the southeastern United States. Their culture is similar to that of Japanese irises. They’ll thrive in anything from standing water to well-watered garden soil, but they’re less fussy about perfect fertility. You may think that their name and southern origin means they won’t be hardy in the North, but I grew many of these successfully when I lived in Michigan. Having said that, they certainly thrive in the Southeast’s heat and humidity.

There are many reasons to love Louisiana irises, not least because they are derived from native U.S. species, but the real place they stand out is in the range of colors in their blooms. Whereas the name “iris” comes from the Greek goddess of the rainbow, iris flowers come in every color of the rainbow except for red. The best that most irises can do is a sort of rusty brownish color that catalog writers try to pass off as red. But the Louisianas are the exception. One of the native species, I. fulva, has red-orange flowers, and plant breeders have taken that starting point and run with it, creating incredible blooms that are red.

‘Ann Chowning’ (I. ‘Ann Chowning’, Zones 6–9) is one of the best, with brilliant red flowers painted with a contrasting point of gold at the base of each fall. But the color diversity of Louisiana irises doesn’t stop at red.

‘Black Gamecock’ (I. ‘Black Gamecock’, Zones 4–9) is an older hybrid whose flowers are the closest to black I think I’ve ever seen in a bloom. And to set that deep, rich, glossy black perfectly, each bloom is broken up just enough by hints of gold to make the black seem even darker. These moody blooms are stunning in a vase but sometimes need careful placement in the garden, as at a distance the black just doesn’t show up. Plant these near a path where you can get up close and marvel at their velvety darkness. It doesn’t hurt to plant or place something light-colored behind them. A clump of ‘Black Gamecock’ growing at the base of a light gray stone wall will leave you weak at the knees.

‘Gerald Darby’ has foliage that rivals its blooms

Many of the water irises have beautiful foliage that’s tall and straight; they almost present the effect of an ornamental grass when they’re out of bloom. The clear standout when it comes to foliar impact, however, is ‘Gerald Darby’ (I. × robusta ‘Gerald Darby’, Zones 4–9). This is a sterile hybrid between two species that are native to eastern North America, I. versicolor and I. virginica, and is one of the most widely adaptable plants I know. It grows happily in standing water, but it also thrived for me when I gardened on well-drained, sandy soil with no irrigation whatsoever. In late spring or early summer, ‘Gerald Darby’ pumps out abundant purple-blue blooms marked with splashes of yellow that have all the grace and simplicity of a wild species.

As pretty as the flowers are, however, the real reason for growing this plant is the leaves. As the foliage emerges in spring, it is flushed over with a dramatic purple, a color that holds a long while into summer before fading to green. To show off those purple leaves, pair them with a bright gold flower. Daffodils are perfect in dry soils; in wet spots, try marsh marigold (Caltha palustris, Zones 3–7). The gold flowers glowing against the purple leaves will make a display suitable for a king.

This article has just scratched the surface of the many wonderful “other irises” you could have in your garden. So take a chance, let the loud-mouth bearded irises step back for a moment, and explore everything else the genus named after a rainbow has to offer.

Things everyone else wants to know, too

Do I have to cut the foliage back like I do with bearded irises?

Cutting back foliage is important for bearded irises to limit damage from iris borers, but they’re not a serious problem for these other irises. I cut or pull off dead foliage as part of spring or fall cleanup, but that’s it.

Can I divide them?

If your irises are happy, they will bulk up and be easy to divide in a few years. The task is pretty straightforward: Dig them up; cut them into sections that have some rhizomes, roots, and foliage (photo right); replant them; and keep them watered. The best time to do this is early spring just before they come into growth, but I’ve done it many other times of the year and had no problems. If you are growing Japanese irises at the northern edge of their hardiness range, I would divide them in spring so they have plenty of time to get established before going into winter. If your irises grow from a bulb, wait until they are dormant, then dig them up and separate the bulbs.

How can I make the area where I plant my irises a little wetter?

You can create wet spots a few ways. Low areas tend to stay wetter, and if you have a level lot, you can excavate a sunken part of the garden to hold some extra water. Guide the downspouts off your gutters or—especially in hot, humid climates—the runoff water from your air conditioner into that sunken area, and you can create a small bog. In very sandy, fast-draining soils, digging out an area, lining it with rubber pond liner, and filling it in with soil again is the ultimate way to create a damp area for wet-loving plants.

Joseph Tychonievich is the author of Rock Gardening and Plant Breeding for the Home Gardener. A graduate of Ohio State University in horticulture, he now gardens in Virginia.

Sources:

- American Meadows, Shelburne, VT; 877-309-7333; americanmeadows.com

- Brent and Becky’s Bulbs, Gloucester, VA; 877-661-2852; brentandbeckysbulbs.com

- Broken Arrow Nursery, Hamden, CT; 203-288-1026; brokenarrownursery.com

- Cascadia Iris Gardens, Lake Stevens, WA; 425-770-5984; cascadiairisgardens.com

- Ensata Gardens, Galesburg, MI; 269-665-7500; ensata.com

- John Scheepers, Bantam, CT; 860-567-0838; johnscheepers.com

Comments

Good job!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in