Plant Some Runner Beans

These versatile legumes are delightful to look at and delicious to eat

Before I knew better, I grew runner beans strictly as an ornamental. Each year, I planted the substantial lavender and black seeds of ‘Scarlet Runner’ and stood back as they sprouted and rapidly clambered up a rustic trellis at the entrance to my garden. By July, the vines bore racemes of striking red-orange blossoms against lush green foliage. The beauty of these blossoms was supplemented by the glittery brilliance of the ruby-throated hummingbirds that darted from flower to flower.

Alerted to the culinary possibilities of runner beans by enthusiastic accounts from friends visiting England, where they are often grown as vegetables, I began to experiment with them in my kitchen. Their taste and tenderness was a revelation and the beginning of my passion for this versatile legume that combines the beauty of the flower garden with the food value of the kitchen garden.

Runner beans, along with other members of the Phaseolus clan such as common and lima beans, are native to the so-called New World. Remains of their pods that may be as old as 6,000 years have been found in a cave in northeastern Mexico, but botanists disagree about whether these were a wild or domesticated type. Today in both Mexico and Guatemala these wild, small-seeded vines can still be found growing as perennials in cool, partially shaded locations where they climb up and over other vegetation.

Although both the Latin name of the runner bean, Phaseolus coccineus (coccineus is Latin for “scarlet”), and the name of its most well-known cultivar, ‘Scarlet Runner’, point to its prominent floral feature, not all runners have these notable red-orange blossoms. The colorfully named ‘Painted Lady’, a Victorian favorite, is a scarlet and white bi-color. ‘Sunset’ has lovely peachy-hued blossoms, and there are a number of whites to choose from such as ‘White Dutch’, ‘Grammy Tilley’, ‘The Czar’ and ‘Desirée’. All white-flowered runners produce plump, delicious white seeds. For the gardener interested in branching out beyond ‘Scarlet Runner’, Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, offers dozens of varieties to its members. This and other sources are listed at the end of this article.

|

|

Pick your size

Just as runner beans come in more than one color, they also come in more than one size, giving the gardener several options for maximizing space and ornamental effect. Besides the familiar pole types, there are also dwarf and intermediate forms.

The dwarf varieties take the blue ribbon for most beautiful bush beans, with their brilliant red-orange blossoms dancing above the foliage. The two commonly available varieties, ‘Dwarf Bees’ and ‘Hammond Dwarf’, grow 1½ to 2 feet tall and are decorative enough to use as a dual-purpose border in a flower garden. Their pods are 4 to 5 inches long.

Half-runners, as the intermediate form is called, send out 3- to 4-foot runners. The best known of these is ‘Aztec Dwarf White’, an ancient variety also called ‘Potato Bean’ and ‘Aztec Half Runner’. This variety stands up to drought and heat better than most other runner beans. In humid areas, it should be grown off the ground on 4-foot poles or tepees. This also provides an elevated stage for the large white blooms that produce 5-inch pods filled with fat white beans.

Pole runner beans grow rampantly 8 to 10 feet and need sturdy support. I grow my favorite black-seeded variety, ‘Black Knight’, over my entry arbor. As I pass each day under this bower of flamboyant blossoms and jumbo bean pods (often at least 10 inches long), I am inspired and dazzled by this combination of vegetative beauty and culinary possibility.

Pole runner beans can also be grown on traditional bean tepees, trellised on nylon or metal netting, or trained up twine that has been zig-zagged up and down the horizontal members of a wooden frame well anchored in the ground.

With the latter method, an end-of-the-season garden clean-up chore is simplified by snipping the twine at the top and bottom and hauling both twine and spent vines out of the garden.In England, runner beans grown for vegetables are trained up X-shaped trellises made of straight 8-foot sapling poles driven into the ground. The X’s stand about 4 feet apart and are connected and stabilized by a horizontal pole that rests on and is lashed to the center of the X.

These ornamental vegetables are useful for shading a window from the blazing sun if you grow them up strings that run from short stakes pounded into the ground to screws driven into the upper frame of the window. They can also be grown in a large box or a planter but need to be kept moist and in a location where hot sun will not cause them to wilt.

Growing couldn’t be easier

Runner beans are gloriously ornamental, they make delicious eating, and all three forms are easy to grow. Sounds like vegetable perfection, but as the poet James Stephens noted, “Nothing is perfect. There are lumps in it.” The lumps in runner beans are low production.

Unlike common beans, which are self-pollinating, runner beans require insects (usually bees) to trip their self-pollinating mechanisms. This characteristic can result in reduced pod formation. A second fact that limits pod production is that these beans are sensitive to high temperatures. Temperatures over 90°F can cause the blossoms to drop. In regions with very hot summers, the best pod production occurs in late summer and early fall.

These versatile legumes are easy to grow throughout most of North America. Except when they’re blooming, they’re tolerant of hot days and cool nights and will germinate in cooler soils than common beans will. Runner beans grow best in well-drained soil high in organic matter with a pH above 6.0. If your soil is low in nitrogen, they will benefit from an early application of soluble nitrogen. In areas of temperate summers, a sunny site is best. In areas like the deep South and the Southwest, where “blistering” is often used to describe a summer day, a site with some afternoon shade is desirable.

In my Zone 4 garden, I plant seeds 1 inch deep in late May, 7 to 10 days earlier than I plant common beans. Those who garden in Zone 3 may want to get a jump on the season by starting seeds in individual 4-inch pots three weeks before the average date of the last frost and then transplanting them when the soil has warmed up.

Keep the seeds moist during their germination and seedling stages. Their quick emergence and rapid growth always reminds me what an appropriate name “runner” bean is. To ensure that their roots remain moist, I mulch with old straw when the plants are 3 or 4 inches high. Gardeners used to the appearance of common-bean seedlings will notice a difference as their runner beans emerge: The seed leaves (cotyledons) remain underground and the vines begin to twine up their support in a counterclockwise rather than the usual clockwise direction. Runner beans also produce a starchy root that may be dug at the end of the growing season and stored indoors like dahlia roots. However, runner beans grow so fast from seed that there is little advantage in storing the roots. In frost-free areas, these tubers are perennial.

The spacing for my runner bean seeds depends on how they will be grown. For growing up a pole, I plant 8 seeds around the base and thin to the four strongest. I space dwarf runners 6 inches in rows 30 inches apart. To train pole runner beans up strings or an arbor, I plant every 3 inches and thin to stand 6 inches apart.

Runner beans are rarely bothered by pests or diseases. However, germinating seeds may become meals for slugs or mice, and root rot may kill plants in soil that is too wet and heavy.

Harvest almost anytime

Harvesting gastronomical delicacies from runner beans begins earlier than you might think. Their edible flowers add a beany flavor to stir-fries and salads, and when scarlet blossoms are used, a spot of vivid color is added as well. Like common beans, runners can be harvested in the snap, shell, and dry stages.

I harvest very young pods between 4 and 6 inches to use as snap beans. At this size, I think their flavor and tenderness are superior to common beans. Since the pods can continue to grow to colossal size (up to 18 inches), snap beans can be harvested over a long period. As they continue to develop, the wide, flat pods resemble Romano beans on steroids. For the best snaps, harvest only flat pods that show no sign of seed development.

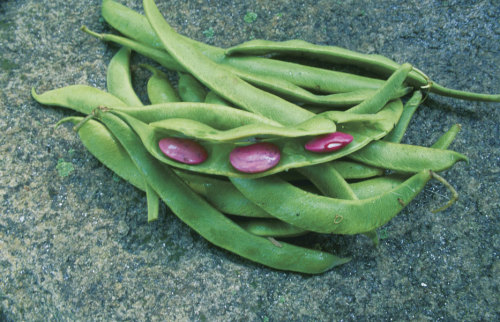

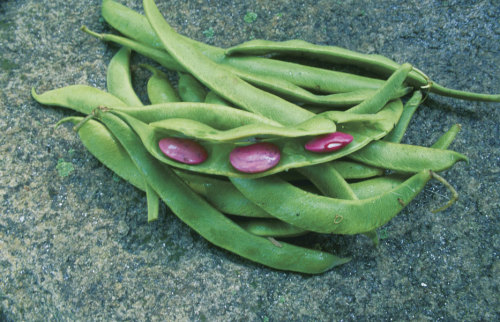

Shell beans, the next stage of harvest, are the seeds formed within the pod. They should be removed from the pod when they are still moist and glossy, before they have started to dry out. Some of the lavender-seeded varieties, such as ‘Scarlet Runner’ and ‘Butler’, are a brilliant, shocking pink at this stage. This color changes into a brownish hue in cooking. Watch for the pods to thin out and become more flexible and the developed beans to show as bulges in the pod.

The final stage of harvest for runner beans occurs when the pods are withered and brittle and the beans within are dry. I gather them into large paper sacks, write the variety name on the outside, and stash them in a dry place until I have time to shell them. This is a pleasant thing about harvesting dry beans—once you’ve picked them, they can be left in the corner until you’re good and ready for them. Runner beans, like the more familiar common beans, are good eating at any stage and can generally be substituted for them in recipes. Because of their large size, shell and dried runner beans require longer cooking than their less generously endowed relatives.

When cooking the first tender snap beans, I like to prepare them whole as simply as possible, the same way I cook fresh peas—simmered for four minutes and dressed with a tad of butter and salt. As the pods get larger and lose their youthful delicacy, longer cooking is necessary and more assertive flavors can be used, such as garlic, olive oil, and lemon juice.

Depending on their size and variety, strings may be present along the sides of larger pods. These should be removed before cooking by gently breaking off a tip and pulling the string downward. Both shell and dried beans maintain their shape with long cooking, which makes them good candidates for soups and stews. When eye appeal is important—in salads, for instance—keep in mind that the vivid magenta and lavender of some of the freshly harvested beans will become muddy beige with cooking. In these cases, I prefer a black or white bean. Since these are such hefty beans, my favorite way of serving them highlights their size. Speared with a toothpick and dunked into a creamy, spicy dressing, they make a crowd-pleasing appetizer.

If you thought these vegetables were merely decorative, think again. To paraphrase an old show tune, runner beans are lovely to look at, delicious to know.

Sources for runner-bean seed

Seed Savers Exchange

3094 North Winn Road

Decorah, Iowa 52101

563-382-5990

www.seedsavers.org

Territorial Seed Company

PO Box 158

Cottage Grove, OR 97424

800-626-0866

www.territorialseed.com

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #20.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in