I learned about the value of mass plantings when my husband and I bought a renovated barn with a large backyard opening to a 3-acre hay field. I liked the fact that our site enjoyed full sun and a magnificent view of mountains, but I was stumped initially by this new gardening challenge. I knew that traditional English perennial beds would not suit the architecture of the barnlike house and that a cottage garden would be dwarfed by the vista.

So I turned to some principles of Japanese gardening. I tried to identify with the pervading spirit of the site, use its strengths, and, most of all, remain sensitive to the existing scale. Given our location, it made sense to place the garden between the expansive view and the house. Mass plantings of low-growing plants seemed the best way to achieve harmony between the garden and the surrounding landscape. These plantings complement, rather than compete with, the natural panorama and can be enjoyed both close up and from a distance. Well-placed mass plantings in any setting can draw the eye and lend a naturalistic air to a garden.

Evaluate the role of mass in your landscape

In gardening terms, mass refers to a body of coherent plantings, usually of indefinite shape and often of considerable size. It can be created by grouping several pots of the same plant or several plants that have similar color, texture, and density. For example, two or three plants that bloom at the same time in a similar color can form a mass. Or several varieties of grasses—even of varying heights—can be combined to make a bold statement.

Since mass is a relative term, it must be developed in relation to other elements—architectural structures, other plantings (such as a shrub hedge), or even open lawn. Looking at the surroundings of my future garden helped in determining an appropriate sense of scale. First, I considered the ratio of the proposed garden (when viewed from the house or terrace) to the imposing backdrop of field, forest, and mountain range. Thinking “big,” I tried to balance the massive scale of the site by breaking up the sloping, rectangular lawn with a 50- by 70-foot pond. This also solved the dilemma of what to do with a gaping hole filled with several huge boulders left behind by the previous owners. We moved the rocks and placed them around the pond.

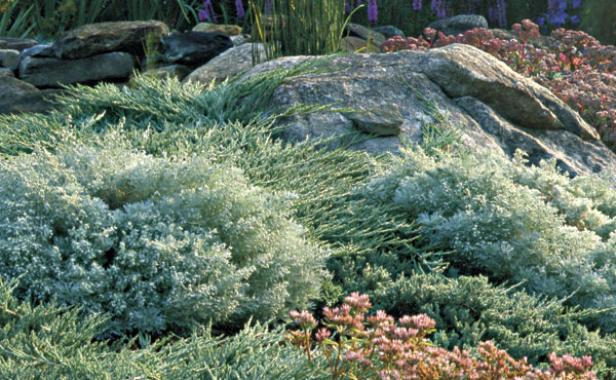

This became a perfect setting for massed plantings. For example, around the side of the pond closest to the house, I planted only low-growing junipers (Juniperus spp.) and cotoneasters (Cotoneaster spp.). Viewed from a distance, these plantings appear as broad sweeps.

Keep masses in proportion

Proportion is key to determining how many plants to mass in an area. For example, in a spot roughly 100 square feet on the far side of the pond, I planted clusters of four different plants—two varieties of Sedum, silvermound artemisia (Artemisia schmidtiana), and snow-in-summer (Cerastium tomentosum). The effect of these combined forms, textures, and colors is akin to the muted shadings of a tapestry.

I alternated these ground-cover masses with low-growing focal points: standards of Juniperus procumbens ‘Nana’ and weeping trees such as Norway spruce (Picea abies ‘Pendula’), katsura tree (Cercidyphyllum japonicum f. pendulum), and Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis ‘Pendula’). They add height and definition to the planting area’s boundaries.

I’ve also found that smaller gardens, or smaller spaces in large gardens, can usually handle some massing of plants. In a walk-in bed behind the pond—about 10 feet wide by 35 feet long—I planted drifts of colorful perennials that draw the eye through the path. As a general rule, I used not fewer than five pots of the same perennial in a section, and in most cases I used 7 to 13. I made exceptions for big plants, such as Nepeta ‘Six Hills Giant’ and Crambe cordifolia. The number of plants I choose, and how I group them, is ultimately determined by eye. Whenever possible, I opt for a naturalistic, flowing style.

In keeping with the open-field style of the landscape, I included prairie plants such as coneflowers (Echinacea spp.), bee balms (Monarda spp.), and monkshoods (Aconitum spp.) punctuated with blue oat grass (Helictotrichon sempervirens). I especially like the hedgelike effect created by a band of black-eyed Susans (Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Goldsturm’) backed by a dwarf fountain grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Hameln’).

Use masses to accentuate color or texture

When planting in masses, the goal is to see broad sweeps rather than insignificant patches of color and texture. Many low-growing perennials look appealing en masse. For example, groupings of plants with textured foliage, such as junipers, heaths (Erica spp.), and heathers (Calluna vulgaris) make excellent foundation plantings when informal, curving lines are desired. And spreaders like dead nettle (Lamium maculatum ‘White Nancy’) and wild ginger (Asarum canadense) are wonderful ground covers beneath trees.

Taller plants can help create a balanced sense of scale along with groupings of shorter perennials. For prairie-style screens or see-through hedges, mass tall native plants such as Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium fistulosum ‘Gateway’) in combinations with grasses such as species of Miscanthus. For a dramatic effect in a woodland area, group large numbers of ostrich ferns (Matteuccia struthiopteris), Japanese painted ferns (Athyrium niponicum), or hostas.

Lackluster plantings, especially shrubs, also can become the basis for creating a mass. One way is to simply plant more of an existing plant or type of plant. For example, a spindly row of lilacs can be transformed into a billowy cloud of color and scent by adding new plants among the established ones. For shrub masses that offer fall and winter interest, plant large clusters of Japanese hollies (Ilex crenata) or Sawara false cypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera).

I also create drifts by filling in spaces between existing plants. I designed a hot border on one side of the lawn by using a spotty arrangement of a dozen or so peonies (Paeonia spp.) as the backdrop for sweeps of plants with foliage or blooms in shades of deep red, yellow, and white

Use annuals as fillers

It’s often difficult to create a finished-looking garden while waiting for plants to mature. Massing annuals around slower-growing plants is a simple way to overcome this challenge. Statuesque plants like Nicotiana sylvestris can add sculptural shapes until new shrubs mature. Ground-hugging annuals will fill in gaps between newly planted perennials and, if they self-seed, can contribute elements of unpredictability and excitement year after year. Given the ever-increasing selections of annuals available, it’s easy to find suitable companions. And, because perennial gardens often lose their luster in the dog days of summer, planting annuals can be a perfect way to perk up the beds. It’s fun to experiment with annuals because the presentation can always be changed the following year.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in