When I came here to Duck Hill 20 years ago, there was no trace of a garden. No terraces, no hedges, no paths or steps surrounded my new home. To my dismay, no flowers bloomed that first spring, except for some wonderful old stands of purple lilacs in the field and by the roadside. The prim 19th-century farmhouse, painted yellow and white, stood slightly forlorn, halfway up a hill. Old sugar maples and white ash lined the perimeters of the property, but the land around the house was virtually featureless. I had a clean slate on which to design a garden. It was an exciting but nonetheless daunting prospect.

I had the good fortune to have lived previously in a home that had been beautifully landscaped in the early 1900s. What especially impressed me was the way the house opened up onto its garden and led your eye—and feet—out along the terraced borders and into the meadow beyond. With that precedent fresh in my mind, I was determined to connect any garden I made to this new home, physically as well as in spirit. Because the house, with its hint of a Greek Revival façade, was basically symmetrical, I felt simple, geometric outlines for the gardens would be most in keeping with the style of the house.

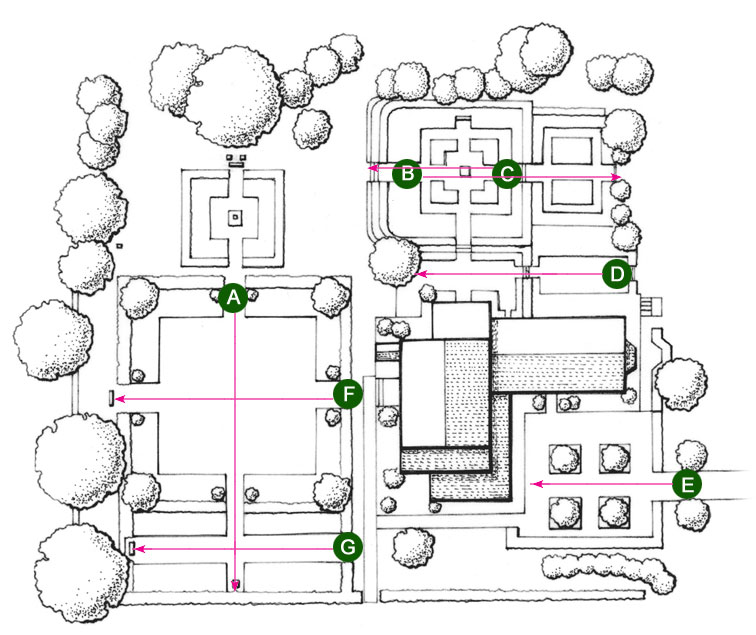

Defining axes helped me turn a daunting project into a more manageable one. Drawing on graph paper at first, then staking out my designs with mason’s twine to see if the scale was right, I planned axes from the front door, from the French doors in the kitchen, and from the porch door, which leads to our parking area. Over a period of 15 years, I built my garden one room at a time, the boundary of each room defined by the addition of a new axis formed by a path, a hedge, or a combination of the two.

Though the classic simplicity of the house suggested gardens formal in outline, I filled the spaces within the axes with an unpretentious jumble of oldfashioned plants. It is a New England sort of garden to my mind, although visitors sometime remark how “English” it appears. Photographs and paintings of gardens in the Northeast at the beginning of the 20th century show just such gardens—square and rectangular mixed flower borders framed by clipped boxwood or yew hedges, all crisscrossed with paths.

Axial views (photos taken from lettered positions)

Let paths draw you into the garden

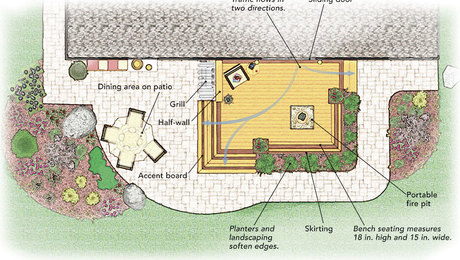

Paths are essential for drawing you out of the house into the garden, and for connecting one garden area to another, leading you on an adventure. At Duck Hill, the straight paths striking off from the doors define the center axis of each garden space. They create perspectives, at the ends of which I like to have some sort of focal point, like a statue, a gate, or a bench.

The materials used for paths depend on garden style and personal preference. I used gravel for most of the paths in my garden because I love the look and feel of it and because it is relatively inexpensive. The brick path that leads from my front door to the side gate was in place when I bought the house, so I left it, since it also seemed appropriate. Most of the gravel paths are edged with brick. I always make the paths at least 4 feet wide, preferably 5 or 6 feet so two people can walk comfortably side by side.

Grass paths can be used where lawn is a prominent feature in a garden room. In the large garden room that sits outside my front door, the axes that crisscross this area are defined by the focal points I placed at the ends of each of the paths. These grass paths are not defined in a formal sense with edging. Instead, properly placed hedges and focal points define sight lines and set up axial movement.

Hedges define space and create sight lines

As I worked my way outside, I formed uncomplicated patterns of hedged-in areas filled with flowers, shrubs, bulbs, and small fruit trees. In this respect, I looked to the great landscape designer Russell Page, who was a master at playing clipped and linear features against wilder flower forms. From the gardens I visited and books I perused over the years, I learned to love the contrast between the straight, clean line of a hedge and the picturesquely irregular growth of flowers and fruit trees.

I chose green hedges to enclose my garden rooms because they’re cheaper frames than walls or fences, but of course, slower to have an effect. What’s more, the fastest-growing hedges, like privet, are the least desirable if the labor of maintenance is a concern. A full-grown privet hedge needs clipping every two to three weeks in summer to keep it shapely. Slow-growing shrubs like boxwood (Buxus spp.), Japanese holly (Ilex crenata), and deciduous summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), on the other hand, need to be clipped only once a year.

Start out with small specimens if you are planting a woody hedge. Taller, more mature shrubs are not only expensive bought in the quantity you’ll need, they also tend to make gangly, leggy hedges. With my privet, barberry, euonymus, and boxwood hedges at Duck Hill, I started with rooted cuttings ordered through the mail. I found that even the lowest hedges—those that were still babies—created lines that defined my garden spaces and reinforced linearity in a satisfying fashion.

While I kept some hedges small, I allowed others to grow to 5 or 6 feet in height. These taller hedges frame views and also create a sense of mystery. By dividing my yard into separate areas with hedges, it seems much bigger and more interesting. My previously open front lawn was seen with one sweep of the eye, resulting in a restful but slightly dull aspect. But now, with my yard divided into smaller connecting spaces, a sense of surprise occurs. You have to turn a corner or pass through an entrance before you can see what’s beyond.

Placing a garden ornament as a focal point at the end of a perspective glimpsed through my hedges not only stops the eye in a pleasing way, but it tends to draw you forward through the garden. A handsome pot or vase spilling with flowers will do, or a trough or pool filled with water that reflects the sky. Perhaps an arbor at the end of a path, with a comfortable wicker chair in its shade, or a wooden bench, with fragrant honeysuckle dripping overhead. Of course, you are lured to this destination, and, taking the time to sit, you are rewarded by a new view the opposite way. .

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in