Photo/Illustration: Peter Hirsdt, courtesy of Purdue Extension

Freeze injury is one of the most common types of environmental plant injuries. Throughout much of the United States, landscape plants (especially trees and shrubs) frequently withstand winter temperatures of 15°F to –20°F. Yet later on, in spring, these same plants may be severely damaged by temperatures just a few degrees below freezing. How is it that a plant that withstood –25°F in January could be damaged by 25°F a few months later? It all has to do with fluctuating hardiness.

The damage isn’t always obvious

Plants can make their own antifreeze

As noted, the real trouble comes from ice crystals forming within cells. One of the ways plants avoid this is through supercooling, or the maintenance of water as a liquid below the freezing point. Supercooling can enable plants to maintain water as a liquid down to –40°F. Some plants survive cooler temperatures by accumulating solutes or creating proteins that further depress the freezing point, like an antifreeze does. These defenses kick in as temperatures drop.

Winter isn’t the only season you need to watch out for

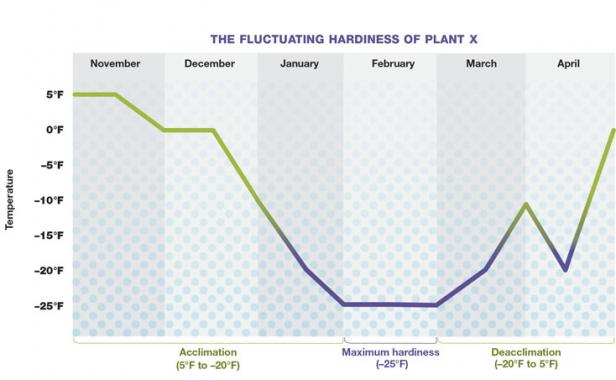

Cold hardiness changes from fall to winter to spring and is divided into three phases: acclimation, maximum hardiness, and deacclimation (graph, above). During acclimation, hardiness increases in response to progressively cooler temperatures. During this time, plants undergo a host of changes, including the accumulation of antifreeze solutes. In most of the northern United States, plants reach their maximum hardiness in January and early February. If temperatures drop low enough to cause freeze injury during maximum hardiness, plants may die. Death, however, is rare among plants that are adapted to where they grow.

Deacclimation is driven by increasing temperatures and happens in late winter and early spring. Unseasonable warmth can promote rapid dehardening, most evident in early blooms of forsythia or magnolia. Deacclimated plants are less cold tolerant than they were a few weeks earlier, so if temperatures drop too low again, damage may occur (just look at the blow our imaginary plant took in April). The injury is usually dieback of new shoots or bud kill.

Plant choices are your best defense

To avoid freeze injury, k now your zone and select plants that are hardy in your location. Remember, though, that zones are just one piece of the puzzle. Take into account sun exposure and other site factors when selecting plants; cool air, for example, drains to low-lying areas and forms frost pockets that create more cold-related problems than in other areas. In addition, you can cover new growth with a bedsheet or frost fabric when frost warnings are issued. In the end, plants selected for their area are the ones that are most able to protect themselves.

Comments

This article was very interesting. I learned a lot about some things I had never understood before, about plants. My city Pittsburgh, zone 6b gets a lot of frost and thaws all winter long and is prone to this.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in